EDITOR’S NOTE: This interview first published on October 19th, 2006.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Welcome to part two of our bazillion-word interview with esteemed jazz critic Francis Davis, wherein our man Fran will be talking non-smack about Coltrane in Philly, Sun Ra on Uranus and the pre-historic beginnings of Fresh Air. If you are just finding us for the first time, you can find Part One here, along with his illustrious CV. When we last left our hero, he was beaten, bloodied and long haired, handcuffed in the back of Philadelphia Police Department paddy wagon charged with aggravated assault and battery on a police officer. In other words, it was the ’60s.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Welcome to part two of our bazillion-word interview with esteemed jazz critic Francis Davis, wherein our man Fran will be talking non-smack about Coltrane in Philly, Sun Ra on Uranus and the pre-historic beginnings of Fresh Air. If you are just finding us for the first time, you can find Part One here, along with his illustrious CV. When we last left our hero, he was beaten, bloodied and long haired, handcuffed in the back of Philadelphia Police Department paddy wagon charged with aggravated assault and battery on a police officer. In other words, it was the ’60s.

Phawker: Okay, so you bust out of prison. It’s you, Tom Waits, John Lurie and Roberto Benigni wading through the swamps of Louisiana. No wait, that’s Jim Jarmusch’s Down By Law. Jumping forward, how did we decide to become a jazz critic?

Francis Davis: Slowly. In 1978, Terry Gross, who, as you know, later became my wife asked me to do a regular jazz segment on Fresh Air. She had a three-hour show in those days. And she needed to fill a lot of time. And she asked me to do a feature on jazz, on out-of-print jazz in particular. I wanted to make it clear that this wasn’t a show by some old white guy in his basement. Like, ‘this record’s really rare.’ I wanted to do a history of jazz paying attention only to the gaps. So I started writing the scripts and working hard to deliver them as if I was just saying these things off the top of my head. And then I got laid off at the record store I worked at which, you know, put me on employment compensation and gave me a lot of time. Terry and I went to England in ’79, and being out of my country for the first time I had kind of metamorphosis in a sense that you had no history. You could be anybody you want to be because nobody knows who you are. [And that was very liberating] So I really started wanting to write when I came back. And I did a few things for the Courier-Post, most of which were not jazz pieces. They paid very badly, but the great part about it was that they didn’t care if you knew something about it or not. As long as there was a Jersey connection, and as long as you remembered to mentioned what high school the person went to.

So I had all this time. I didn’t have a lot of clips, but I had a lot of the scripts, which were very good scripts actually. You know, a little over-written, but it goes with the territory when you first start to write… And I was on unemployment compensation, so I was getting a check every week and I could just sit and write. And do, like, 20 records reviews a day. And sometimes I did. So I built up this body of work and eventually people noticed me…

Phawker: Were you as interested in pop music or rock and roll as you were in jazz?

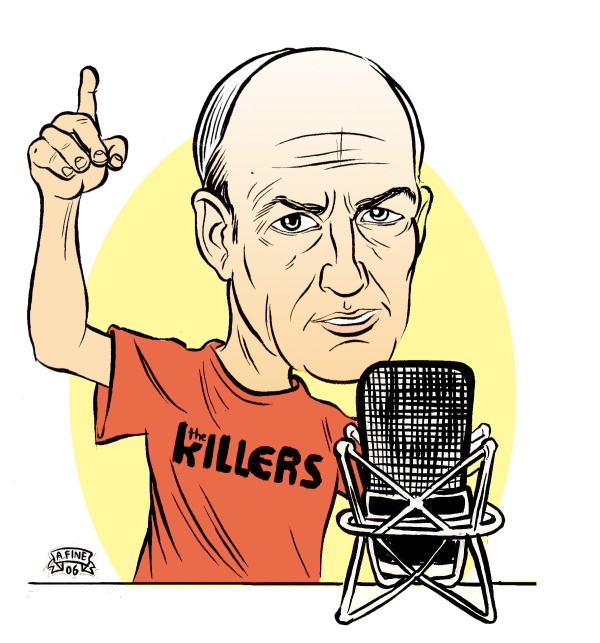

Francis Davis: Yeah, at one point I was. But writing about music for me meant writing about jazz, you know. And the other thing is that insofar as pop music is youth music, there has to be a point at which — and this certainly isn’t true for Bob Christgau — but for most of us there has to be a point at which keeping up with it, as I put it in the intro of Like Young, becomes as absurd a notion as keeping up with sex, or something. By the way, everybody hates the Killers new CD. I kind of like it, but anyway.

Phawker: How long was your little segment, about five minutes or so?

Francis Davis: Well, that’s what we always joked about. No, it was supposed to be 20 minutes, but because we had all the time in the world to fill, it was ‘Hey, 37 minutes? Fine! The guest isn’t here yet.’ And the show was live in those days too. They had very few things on tape.

Phawker: Was it called Fresh Air then?

Francis Davis: Yeah, my segment was called Interval. And you know, part of the time would be taken up by playing records. I didn’t excerpt records. I played complete tracks. That’s one thing I never liked about reviewing for NPR shows. I don’t know what you get from playing 30 seconds of something. Getting back to your question about pop, I’ve written about pop but usually just because something had interested me for years and years, like the piece I wrote about the Velvet Underground.

Phawker: Where did the Velvet’s piece first appear?

Francis Davis: The Atlantic Monthly. But that was because Bill Whitworth, the editor, asked me if I’d be interested in writing a piece about the Rolling Stones, who were mounting one of their many tours at the time. This I guess this is ’89 or ’90. And you know, no I wasn’t.

Phawker: Didn’t you call them ‘blown-out satyrs’?

Francis Davis: That’s the first sentence of the piece. I think I can write on a very personal level about pop. But I don’t think I have the kind of weight of authority that I have when I’m writing about jazz. And it’s the same thing. Bob Christgau has written about jazz but I think pop critics are treading on very dangerous territory when they write about jazz. And even Bob’s got stuff wrong. I don’t mean factually wrong. Its something I just disagree about. I think opinion is non-negotiable. It’s my way or the highway. But no, I don’t feel the need to sort of share my opinion with’ about the new Beck record, which I haven’t heard, as I do to share my opinion of the new Ornette Coleman record.

Phawker: Just to finish up the Terry thing. Is that how you guys met? Through the show?

Francis Davis: No, I think the first time we met was in the store. I dunno, the first or second time. And I remember we had a conversation about Ella Fitzgerald and about Paul Desmond. Because I really loved Paul Desmond. And she was surprised given my taste for, like, free improvisation and so on, that I liked Paul Desmond. I want to write a piece about Paul Desmond by the way.

Phawker: I don’t know anything about Paul Desmond.

Francis Davis: Paul Desmond was the alto saxophonist in the Dave Brubeck Quartet. And in a way one of the whitest players that ever lived. But in a sense he was the token black in the Brubeck Quartet. At least until before they hired a black bass player. He was a very ‘black’ player. I mean, there are many, many tenor players, including white tenor players, who were influenced by Lester Young. And the influence is kind of transparent. Because Desmond’s playing another instrument, an instrument in a high register, it’s not as obvious. But Desmond is so far behind the beat and so Lester Young-like, but in a good way. Anyway, but that’s how we met.

Phawker: And you sort of hit it off from there and the rest is history?

Francis Davis: Well, she knew I knew a lot about jazz and wanted to do a whole strip of different music features. There’d be one on jazz, there’d be one on folk music or something, and actually I was the only one who did it for a long time because people would lose interest. In fact, I think in the end we weren’t getting paid anything, or maybe $20 a throw.

Phawker: Lets jump ahead. You have been working on a Coltrane book for 10 years…

Francis Davis: Yeah. Fitfully. It’s long overdue. I don’t mean it’s long overdue in the market, I mean, in terms of the contract, it’s long overdue. Yeah, I have a very indulgent publisher. It’s a straight bio. But the publisher would be horrified to hear it described as a critical biography because they always fear that. In the marketplace that means it’s a kind of dense book that’s not really a biography but really a book of criticism. But you know, these things weave in and out. And I don’t know how you can write a biography of an artist without it being a critical biography in some ways. There have been numerous Coltrane biographies, but I think what’s missing, really, is Philadelphia. Because there were a lot of people, there still are a lot of people here, who are kind of important to the story who nobody really bothers talking to very much.

Phawker: What role do you think Philadelphia played in his art?

Francis Davis: Well, what was he, 18 when he came here? I dunno, he had finished high school. He studied at the Granoff School. I think in Philadelphia there were two things that had an impact on him. I don’t know if there’s such a thing as a Philadelphia sound. I think there’s a Philadelphia mind set, or sensibility or attitude or whatever. The other thing, the thing he became caught up in, musicians will tell you, and it’s funny, some people intend it as a criticism, that there was an obsession with technique in Philadelphia. And it’s funny, with Coltrane that technique becomes a form of mysticism. It’s almost as if like, the deeper you get into chords, the better of a musician you are, the better person you become. It’s such a discipline. Its almost like this zen kinda that. And that’s Philadelphia. And Coltrane came to epitomize that.

Phawker: When was Coltrane here?

Francis Davis: Well he got here about ’44, ’45. Again, he didn’t come here for the music. He came here for the work, along with his mother, who had recently been widowed. When he left it’s kind of hard to say. He left gradually. He maintained a residence here. Which is still there, but I’m not sure when he last actually resided here. But he was gone by ’57. He joins Miles [Davis] by ’55 and he’s kind of gone by then really. Sometimes you read things and you think Coltrane lived his whole life here or something, because Philadelphia is very possessive and it has a king-sized inferiority complex because of its proximity to New York.

(At this point, Terry calls and Francis excuses himself to make a dinner date with his wife at Zeke’s Deli. If you go, try the whitefish. Dynamite whitefish. Lastly, apologies for false advertising, there was a fairly lengthy Sun Ra discussion that must have wound up on the cutting room floor. We’ll look for it and slap it on the end if we find it [We never did.–The Editor]. We blame the intern. That’s the beauty of having an intern. At Phawker our motto is: We’ll get it right, eventually.)