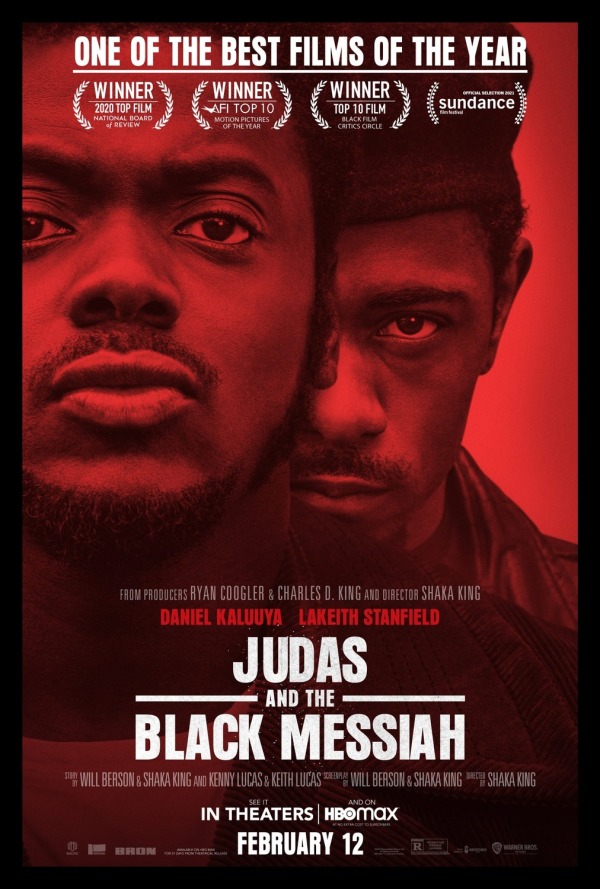

JUDAS AND THE BLACK MESSIAH (dir. by Shaka King, 126 minutes, USA, 2021)

![]() BY DAN TABOR FILM CRITIC It’s rare that you see a first time filmmaker just race out of the gate with such a grand and assured debut, which feels like something a more seasoned filmmaker could work their entire career and never achieve. But Shaka King has accomplished just that with his second feature Judas and the Black Messiah. The ambitious biopic which just premiered at Sundance is based on newly declassified documents similar to MLK/FBI and Seberg, and if you’re thinking there’s a pattern starting to surface here with these films I mentioned, you’re probably right. Judas further cements what were once simply conspiracy theories, of how government agencies were instrumental in the assination of any person that looked to put an end to systemic racism and champion unity.

BY DAN TABOR FILM CRITIC It’s rare that you see a first time filmmaker just race out of the gate with such a grand and assured debut, which feels like something a more seasoned filmmaker could work their entire career and never achieve. But Shaka King has accomplished just that with his second feature Judas and the Black Messiah. The ambitious biopic which just premiered at Sundance is based on newly declassified documents similar to MLK/FBI and Seberg, and if you’re thinking there’s a pattern starting to surface here with these films I mentioned, you’re probably right. Judas further cements what were once simply conspiracy theories, of how government agencies were instrumental in the assination of any person that looked to put an end to systemic racism and champion unity.

Judas is the story of Bill O’Neal (Lakeith Stanfield),an apolitical street hustler who is ensnared early on by the FBI when he’s busted for impersonating a federal agent to boost cars. Bill, aka the titular Judas, is unwittingly living out the old saw that goes: ‘if you don’t believe in anything, you will fall for everything.’ Bill is recruited by Agent Roy Mitchell (Jesse Plemons) to be a paid informant to help infiltrate the Black Panthers. Their target is Fred Hampton (Daniel Kaluuya), the charismatic chairman of the Panthers’ Chicago chapter, who has begun reaching outside of the black community with his mission of unity that has landed him in the dead center of J. Edgar Hoover’s crosshairs — emphasis on the dead. The film borrows a bit from The Departed (by way of Infernal Affairs) for the narrative engine of this tragedy wherein Bill almost loses himself while discovering he might have picked the wrong side. This is highlighted by King who masterfully interweaves interviews with the real Bill O’Neal who gives his hindsight perspective on those chilling events of 52 years ago.

O’Neal begins the film with an idealistic view of the FBI, but all that changes when he is brought in by a man from the Bureau who replaces that idealism with fear. Like O’Neal, the audience learns that there was a very good reason black power activists like the Black Panthers were militarizing: the US government was trying to wipe them out as part of their strategy for sabotaging the civil rights movement. Hoover used the Bureau’s nearly unlimited powersfor fuckery to disinform the American people about the the true intentions of the Panthers. The film sets the record straight in the process of telling the story of the betrayal that led to Chairman Fred’s assassination at the young age of 21.

Stylistically the film feels just period enough to have happened in the late ‘60s while evoking a very contemporary vibe to supercharge the present-day relevancy of the film’s subject matter. This all transpires to the beat of an experimental jazz score that does a profound job at externalizing the chaotic internal voices of the characters. While the betrayal is definitely at the forefront of the film’s narrative, it’s Chairman Fred’s romantic relationship with fellow Panther Deborah Johnson (Dominique Fishback) that gives us a real glimpse into the soul of the man. It is those moments of calm between the couple keeps the viewer invested as the devious machinations of the FBI are put into motion. Kaluuya and Stanfield turn in career-defining performances in this tragic tale that needed to be told. With all these secret histories coming to light as more and more of the Bureau’s files being declassified, the fear, paranoia and resulting radicalization of groups like the Panthers seems not only justified but necessary. After all, in 1969 Hoover’s G-men were the de facto enforcers of white supremacy, hunting and assassinating black activists whose only crime was pursuing equality.