THE GUARDIAN: The title is a prophecy, a warning, or a vengeful supernatural pronouncement. Paul Thomas Anderson’s strange masterpiece, freely adapted by him from Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel Oil!, is a tragic parable of man’s dependence on this commodity: formerly the lubricant of commercial triumph and technological innovation, and now the dwindling lifeblood of our material prosperity, the unacknowledged driving force of our military conflicts, and even the cause of a coming ecological catastrophe. That dark title threatens a calamity now visible on the horizon: destruction of the Earth itself. And it is all inscribed in the story of the movie’s leading character, a man with the Bunyanesque name of Daniel Plainview.

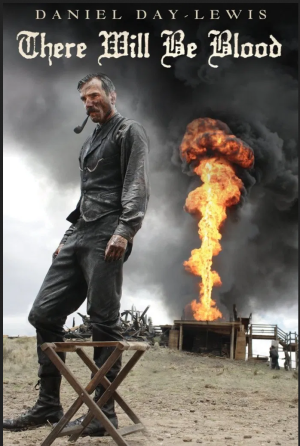

Daniel Day-Lewis gives perhaps the greatest, certainly the most exotic performance of his career as an oil prospector in the early 20th century, rewarded with colossal wealth that never gives him the smallest pleasure and serves only to amplify the loneliness, paranoia and resentment that were there from the very beginning. Day-Lewis seems to have unlocked this character’s mystery by seizing on a voice: a robust, cantankerous Scots-Irish accent that he has modified from John Huston (a borrowing that itself may have a subtextual reminder of Huston directing The Treasure of the Sierra Madre). As a poor man, Plainview is seen hacking fanatically away in a silver mine, to the accompaniment of an eerie, atonal score by Radiohead’s Jonny Greenwood: he accidentally discovers oil, like the apes at the beginning of Kubrick’s 2001 discovering their opposable thumbs.

The movie perhaps looks even stranger, starker and more unforgiving now than when it was released in 2007. Since then, Day-Lewis has given more emollient and sympathetic performances: as Abraham Lincoln for Spielberg in 2012, and as the fictional English couturier Reynolds Woodcock for Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread in 2017. Compared with either, Plainview is uncompromising and uningratiating, and it is a grandiloquent performance that could be expected of no one else. Perhaps not Olivier in his screen heyday would have tried something so melodramatically strange – and yes, the weird “milkshake” monologue at the end  now feels a bit exposed. No one other than Day-Lewis could have carried it off. The film is also intensely, disconcertingly male, a story of male toxicity without any real female dimension. MORE

now feels a bit exposed. No one other than Day-Lewis could have carried it off. The film is also intensely, disconcertingly male, a story of male toxicity without any real female dimension. MORE

THE GUARDIAN: According to my anecdotal, longitudinal survey, no other film has so captured the heterosexual male imagination in more than a decade. There may be some bias: for many men of my age, There Will Be Blood might have been the first auteured film they “discovered” for themselves, marking the transition from a boy to a man with an Esquire subscription.

As for me, I’ve been asked, “Have you seen There Will Be Blood?” so many times, I count it as a relationship milestone – yet I’ve still not seen it. My first attempt was in 2012, when my boyfriend at the time – a film buff in the completist way that only a third-year university student can be – sat me down in front of the laptop with the quiet conviction of someone who can’t wait for you to see the light. Instead I fell asleep long before Daniel Day-Lewis made it out of the dark hole in the excruciatingly protracted opening sequence. My boyfriend was disappointed – but happy to watch it again.

My second viewing was a few years later, after enough mentions that I had started to wonder: is it actually men, or is it something about me? Again, I fell asleep – at a later stage this time, but still having got nowhere close to grasping the film’s widely-agreed-on genius. “Was there a very white room?” I hazarded on waking, single-handedly causing a crisis of masculinity. “Something about milk?”

Sure, maybe I should get my iron levels checked. Or maybe it’s more that a film has to hold my attention. Even from the little of it I had seen, it was clear that There Will Be Blood seeks to impress on you how important it is – in being not only long but slooow, with capital-A acting and a dissonant score – more than it actually wants to engage you. I have always felt an aversion to art that seems to hold itself above people. Not to dismiss the importance of auteur’s vision, or audiences willing to meet them on their terms, but when it has come to the choice between making a statement and delivering entertainment, I’ve wondered: why not both? MORE