EDITOR’S NOTE: John Prine passed away today of complications from Covid19. So we’re re-posting Jonathan Houlon’s tribute penned a week ago upon the news that Prine had contracted Covid19 and was in the ICU on a ventilator. Jesus Christ died for nothing, I suppose. Goddamn.

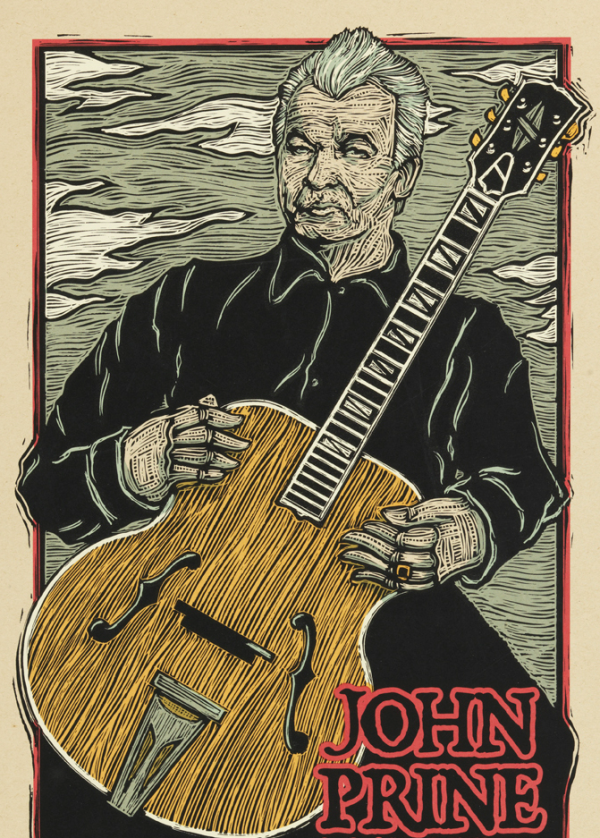

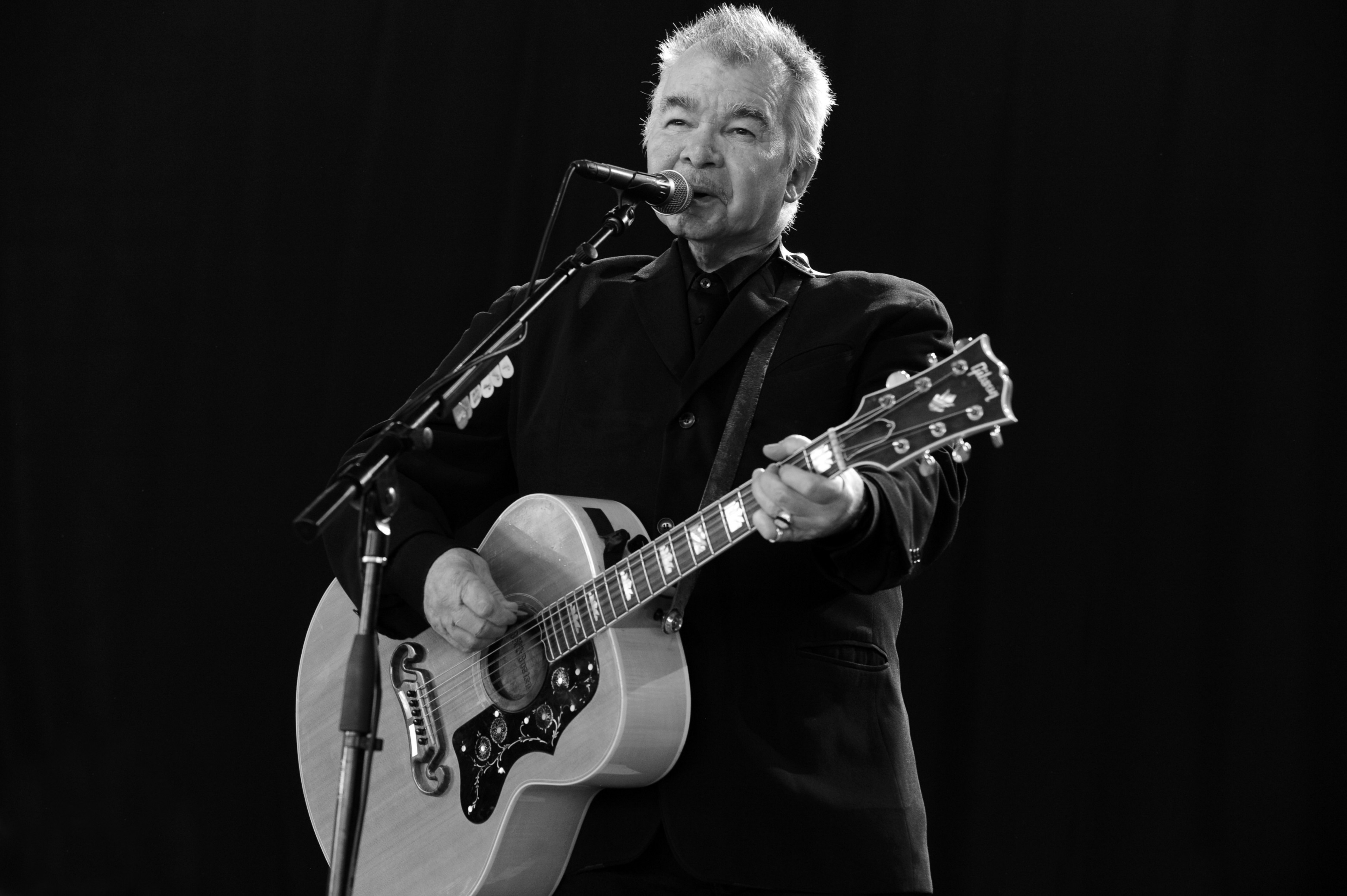

BY JONATHAN HOULON If you haven’t heard, sad news from Nashville: John Prine, folksinger-songwriter extraordinaire and a goddamn national treasure, is on a ventilator with Covid-19 symptoms. If anyone can beat this thing, it’s Prine — he’s proven to be pretty much un-killable. He’s already stood up to cancer. Twice! One of his bouts and its attendant surgery left his head in a permanently cocked position, sorta like a lost dog shown a card trick. It only seemed to add to his Prine-ness.

BY JONATHAN HOULON If you haven’t heard, sad news from Nashville: John Prine, folksinger-songwriter extraordinaire and a goddamn national treasure, is on a ventilator with Covid-19 symptoms. If anyone can beat this thing, it’s Prine — he’s proven to be pretty much un-killable. He’s already stood up to cancer. Twice! One of his bouts and its attendant surgery left his head in a permanently cocked position, sorta like a lost dog shown a card trick. It only seemed to add to his Prine-ness.

A singing mailman — which was his day job at the time, he would write songs in his head as he made his appointed rounds through sleet, snow, fire, famine and whatnot — Prine emerged onto a then-withering folk  scene back in 1971. Somehow he got the attention of folk singer-songwriter Steve Goodman who dragged Kris Kristofferson to see him after hours in a Chicago folk club. Can you imagine auditioning for Kris Kris who then (and really still) was considered just a notch below Dylan as the greatest songwriter alive? You alone on stage, with the chairs stacked up on the tables? Well, the mailman delivered.

scene back in 1971. Somehow he got the attention of folk singer-songwriter Steve Goodman who dragged Kris Kristofferson to see him after hours in a Chicago folk club. Can you imagine auditioning for Kris Kris who then (and really still) was considered just a notch below Dylan as the greatest songwriter alive? You alone on stage, with the chairs stacked up on the tables? Well, the mailman delivered.

Prine’s self-titled debut album, which came out on Atlantic shortly after that famed night in Chi-town, has got to be among the finest debuts of all time. Its tracklist practically reads like a greatest hits: “Hello in There,” “Angel From Montgomery,” “Sam Stone,” and “Illegal Smile.” These songs became part of the folk lexicon and are as likely to be sung around a campfire as, say, “This Land is Your Land” or “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Instant classics.

While Prine may never have topped his first album (at least in terms of material), he’s gone on to write more aces than anyone has a right to. His catalogue is the envy of all of those who claim to be songwriters. How about this rhyme from “The Speed of the Sound of Loneliness”? (off 1988’s German Afternoons, a personal favorite of mine): “You come home late and you come home early // you come on weak when you’re feeling small // you come home straight and you come home curly // some times you don’t come home at all.” Jeez. Prine was called a new Dylan when he first emerged (he mighta been the first one to inherit that preposterous sobriquet) but Bob would never have come up with “curly.” Prine has a way of making sense out of nonsense. Curly? Perfect.

Prine’s other strong suit is compassion and empathy. He’s often funny but never cruel or petty in the way Dylan can often be. Whether writing about old people, fat people, people putting people down, or whoever, JP’s thing has always been empathy and we could sure use some of that now.

So, to borrow a phrase from Prine co-writer Peter Case, here’s a 6-pack of love for John in the form of half a dozen covers. Another unique and incredible thing about Prine’s stuff is that it’s at once completely idiosyncratic yet lends itself to interpretation. Not an easy trick!

1. “Angel from Montgomery” by Bonnie Raitt: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=toJ3ZYWRh24 Yea, I know. This is sorta obvious for a trainspotter like me but not only is this undoubtedly the most famous version of one of Prine’s most famous songs, it’s also the best. Listen to how in the last verse Bonnie leans into the word “hell” when she sings “How the hell can a person go to work in the morning and come home in the evening without a damn thing to say?” Whew!

2. “Paradise” by Kelsey Waldon: Kelsey is actually signed to Prine’s “Oh Boy” label and I urge you to check out her White Noise/White Lines release which came out last year. Kudos to Prine for not only being one of the first major artists to open his own shop but also for the support he has given others in developing their careers. The guy’s a mensch. Paradise instantly became a bluegrass standard upon its release. I love the banjo on Kelsey’s version and her voice is pure Kentucky (from whence she hails), perfectly fitting the subject of this song. Kelsey understands. If you dig Margo Price, don’t miss Miss Waldon. I saw her blow the roof off of Milkboy last year with a band of Nashville shit kickers and their old school chops.

3. “Hello in There” by David Allan Coe: I love the tension between DAC’s alpha-male/pirate/cowboy/biker vibe and the gentle sentiment of this Prine standard. And listen to the cool outlaw thump David achieves on the chorus. DAC’s overdue for a revisionist take on his mostly overlooked catalogue of great records from the 70s and early 80s. He sure didn’t do himself any favors with his x-rated material (Susie Shallowthroat, anyone?) but I actually think he’s up there with Hag and George Jones. Now that I’ve got some time maybe I’ll write something up about DAC. Maybe not. [Please do. –The Ed.]

4. “Souvenirs” by Paul Westerberg (aka Grandpaboy): Westy really hit his stride as a solo artist when he slipped the majors and started recording at his house. As with the best of the ‘Mats, he achieves a ramshackle feel here well suited to this cut from Prine’s 2nd record, Diamonds In The Rough. Paul’s one if there ever was. And, like Prine, Mid-West through and through.

5. “People Putting People Down” by Bob Dylan: If you can make out what Bob’s on about in the introduction to this live version of Prine’s song, you’re a better Bobcat than me. If you’re not a Bobcat, this version of a sleeper track off of 1984’s Aimless Love (incidentally Prine’s most underrated record) won’t make you one! The Master acknowledging another one.

6. “Speed of the Sound of Loneliness” by John Train: Nanci Griffith did this one justice but these local yokels do it better. I sure miss Fergie’s and look forward to seeing everyone again soon. Better times ahead!

Awww, man. Can’t end on a weeper like that one. So let’s make it a lucky seven.

7. “Space Monkey” by John Prine: The man himself singing up one he co-wrote with Peter Case. This song answers the musical question, what happens when you lock two of America’s finest in a room and tell them to get to work?: they write a song about a monkey lost in outer-space.

Godspeed, John Prine!

PREVIOUSLY: Funny how the more wars change, the more they stay the same. In 1968, at the height of the Vietnam War, John Prine, quintessential Americana songwriter, then fresh out of the Army and well-acquainted with the Catch 22s of a soldier’s life, wrote “Sam Stone.”

You may not recognize it from the title, but you have heard this song. Detailing the post-traumatic stress of a Vietnam vet all but abandoned by the country he nobly served, the lyric goes: “There’s a hole in  Daddy’s arm where all the money goes/ Jesus Christ died for nothing, I suppose.” Intended as a snapshot of a bleak moment in this American life, Prine never meant for the song to remain so painfully relevant almost 40 years later. “At the time, I fully expected the song to be irrelevant by the end of Vietnam,” Prine told me during a rare interview from his home in Nashville back in 2007.

Daddy’s arm where all the money goes/ Jesus Christ died for nothing, I suppose.” Intended as a snapshot of a bleak moment in this American life, Prine never meant for the song to remain so painfully relevant almost 40 years later. “At the time, I fully expected the song to be irrelevant by the end of Vietnam,” Prine told me during a rare interview from his home in Nashville back in 2007.

In the wake of recent disclosures of shabby treatment of disabled vets at Walter Reed Army Medical Center and a growing chorus of disgruntled Iraq war vets going public with tales of the government giving them the short end of the stick, the song retains a tragic currency. “But the demand for it only gets stronger – I’ve never been able to give a concert without playing it,” said Prine.

While the theme extends the theory that the war is creating yet another lost generation of damaged young men neglected by the government they served and invisible to the citizenry they defended, there is a crucial difference between Iraq and Vietnam, said Prine. “Back then, there was a silent majority that might question the patriotism of people who spoke out against the war, but nobody in the government would ever talk like that,” Prine said. “Today, it’s the vice president that talks like that. That’s really dirty stuff. I can’t believe that in 2007 people are acting like this. It’s really not progress.” – JONATHAN VALANIA

RELATED: John Prine On American Routes