NEW YORK TIMES: Krzysztof Penderecki, a Polish composer and conductor whose modernist works jumped from the concert hall to popular culture, turning up in soundtracks for films like “The Exorcist” and “The Shining” and influencing a generation of edgy rock musicians, died on Sunday at his home in Krakow. He was 86.

Mr. Penderecki was regarded as Poland’s pre-eminent composer for more than half a century, and in all those years he never seemed to sit still. Beginning in the 1960s with radical ideas that placed him firmly in the avant-garde. […] It was compositions from the wild first decade of his career, including “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima” (1960), “Polymorphia” (1961) and the “St. Luke Passion” (1966) that brought him lasting international recognition while he was still a young man.

The threnody, in particular, is a much-studied example of startling emotional effects created from abstract concepts. Following a score that often looks more like geometry homework than conventional notation, it forces an ensemble of 52 string instruments to produce relentless, nerve-jangling sounds that can suggest nuclear annihilation. Yet it was said that Mr. Penderecki dedicated it to the victims of Hiroshima only after hearing the piece performed. MORE

VULTURE: The most startling flashback in the history of American television is the one that takes us from a black screen to the first successful test of an atomic bomb in New Mexico, on July 16, 1945, at 5:29:45 a.m. (Lynch and Frost make sure to note the time as well.) It might or might not be significant that the first detonation was code named Trinity, and this series is built around a trinity of Dale Cooper figures: the BOB-possessed Coop, the “good” Coop who’s been trapped in the Black Lodge for 25 years, and Dougie Jones, an outwardly ordinary executive at a Las Vegas insurance firm who, in the Lynch tradition of beetles beneath green lawns, secretly has a mistress and a prodigious gambling problem. The mushroom cloud (CGI, not stock footage) is observed from a high, moving angle. This vantage point takes a godlike view of  humanity assuming the power of a god, initiating a military-industrial complex Frankenstein narrative. The music, significantly, is Penderecki’s “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima,” an “unorthodox, largely symbol-based score” that “sometimes directs the musicians to play at various unspecific points in their range or to concentrate on certain textural effects.” (Rather like Twin Peaks itself.) Bits of Penderecki’s piece have been used in other genre works with a strong horror component, notably Children of Men, The People Under the Stairs, and The Shining.

humanity assuming the power of a god, initiating a military-industrial complex Frankenstein narrative. The music, significantly, is Penderecki’s “Threnody for the Victims of Hiroshima,” an “unorthodox, largely symbol-based score” that “sometimes directs the musicians to play at various unspecific points in their range or to concentrate on certain textural effects.” (Rather like Twin Peaks itself.) Bits of Penderecki’s piece have been used in other genre works with a strong horror component, notably Children of Men, The People Under the Stairs, and The Shining.

That last film is notable because of the Stanley Kubrick connection. The section following the bomb blast is structured as an homage to the “Stargate” sequence that ends Kubrick’s 1968 classic 2001: A Space Odyssey. That work and this one are both so clearly concerned with ideas of evolution (and the role of weapons in furthering evolution) that it’s safe to say that Lynch is leaning into the comparison. Confidently, too.

It is the highest praise to say that, of all the filmmakers who’ve referenced the final section of 2001, Lynch seems to me the only one to have created something that equals it even as it humbly bows to its example. The post-bomb sequence takes us through what appears to be a series of tunnels, some comprised of nuclear hellfire but others of a more tantalizingly organic texture (as if to literalize the idea, expressed in Kubrick’s tunnels of light, that humanity was “reborn” after 1945). The use of the bomb claimed hundreds of thousands of Japanese lives, and was justified retroactively as necessary to make Japan surrender, but even in the immediate aftermath of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, historians, tacticians, philosophers, and pundits questioned whether any strategic objective could justify unleashing a genocidal monstrosity of science, the likes of which not even the prophet Mary Shelley could have imagined.

The episode is filled with figures and creatures that seemed to have slithered out of primordial ooze even as their appearance is accompanied by electronic or electrical distortion noises (notably, David Lynch  serves as his own sound designer on this series). The post-bomb sequences feel like a nightmare of Eisenhower/Kennedy–era American hypocrisy, with the proverbial chickens of the atomic age coming home to roost via a series of invasive and brutal acts, perpetrated against oblivious Americans in small town or suburban settings. (Speaking of chickens: See Eraserhead’s chicken baby.) They’re just going about their business, working in soda shops and enjoying innocent dates and broadcasting songs at a Podunk radio station, while unbeknownst to them a hideous evil unleashed by the bomb is secretly creeping up on them, preparing to squeeze the blood and brains from their heads, crawl inside their sleeping mouths, or (in the case of the coffee-shop waitress) knock them unconscious with Lynchian record-skip noises and incantations broadcast over the same airwaves that previously offered golden oldies.

serves as his own sound designer on this series). The post-bomb sequences feel like a nightmare of Eisenhower/Kennedy–era American hypocrisy, with the proverbial chickens of the atomic age coming home to roost via a series of invasive and brutal acts, perpetrated against oblivious Americans in small town or suburban settings. (Speaking of chickens: See Eraserhead’s chicken baby.) They’re just going about their business, working in soda shops and enjoying innocent dates and broadcasting songs at a Podunk radio station, while unbeknownst to them a hideous evil unleashed by the bomb is secretly creeping up on them, preparing to squeeze the blood and brains from their heads, crawl inside their sleeping mouths, or (in the case of the coffee-shop waitress) knock them unconscious with Lynchian record-skip noises and incantations broadcast over the same airwaves that previously offered golden oldies.

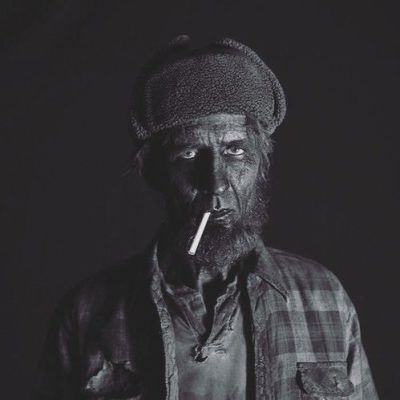

The mind-bending climax of the episode intertwines images of the “got a light?” guy invading the radio station and crushing employees’ skulls with shots of a hideous frog-cockroach hybrid, seemingly hatched from an egg on the nuked salt flats of New Mexico. Both narratives of creeping violence have the feel of a curse being visited upon a society that tacitly condoned one of history’s greatest sins, nodding to a rich tradition of post–World War II science-fiction cinema in which monsters birthed by atom bomb tests (and other scientific or military experiments that were essentially stand-ins for atom bomb tests) menaced teenagers and their adult guardians in Norman Rockwellian small towns and suburbs. MORE