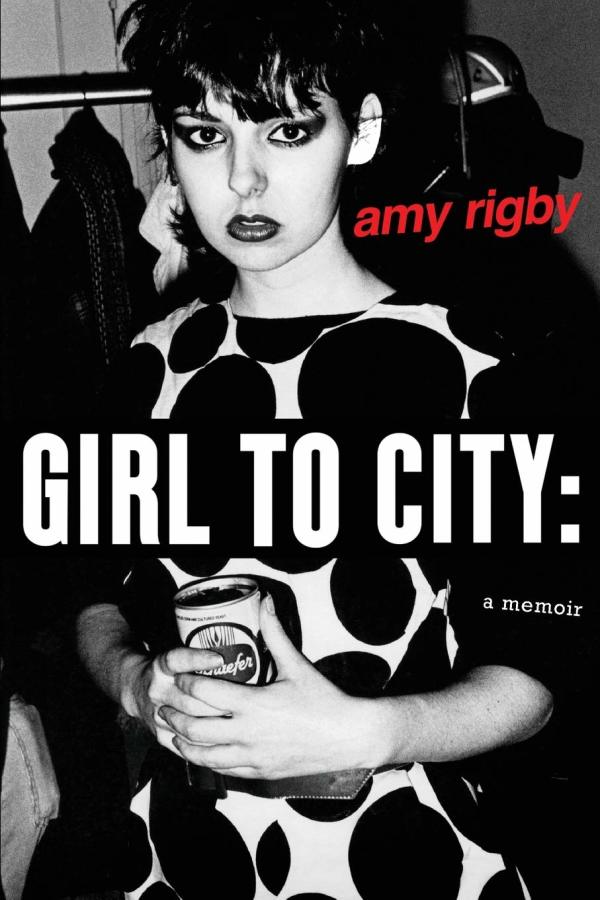

BY SOPHIE BURKHOLDER A Catholic-raised Pittsburgh girl, Amy Rigby fled her steel mill hometown for New York, then in its mid-70s punk prime to attend Parsons School of Design. Soon shrouding her eyes in black liner, she quickly became a fixture at CBGB and fell into a crowd of downtown punk scenesters. Her love of music grew into a passion for making her own, first with bands like Last Roundup and The Shams, and later on her own. Her first solo album, 1996’s Diary of a Mod Housewife, received widespread critical acclaim in the press a few short years before the dawn of the Internet. Last summer, Rigby wrote an equally praised memoir about all this and more called Girl to City, whose title references the classic “Ford to City” headline of New York newspapers in the 70s. We got her on the phone to talk about her Pittsburgh roots, increasing interest in female rock memoirs, and how she feels about faith and religion these days.

BY SOPHIE BURKHOLDER A Catholic-raised Pittsburgh girl, Amy Rigby fled her steel mill hometown for New York, then in its mid-70s punk prime to attend Parsons School of Design. Soon shrouding her eyes in black liner, she quickly became a fixture at CBGB and fell into a crowd of downtown punk scenesters. Her love of music grew into a passion for making her own, first with bands like Last Roundup and The Shams, and later on her own. Her first solo album, 1996’s Diary of a Mod Housewife, received widespread critical acclaim in the press a few short years before the dawn of the Internet. Last summer, Rigby wrote an equally praised memoir about all this and more called Girl to City, whose title references the classic “Ford to City” headline of New York newspapers in the 70s. We got her on the phone to talk about her Pittsburgh roots, increasing interest in female rock memoirs, and how she feels about faith and religion these days.

PHAWKER: Like you, I’m from Pittsburgh. As I read the beginning of your book, I really got the sense that you felt a real need to get out of Pittsburgh, that it was a backwater town, at least compared to like a cosmopolitan place like New York. I don’t know if you’ve been back to Pittsburgh recently, but assuming you have what do you think of it now?

AMY RIGBY: Yeah, my dad still lives there and so do a couple of my brothers who originally left as well, but then they ended up back there. I’ve  definitely gone back plenty of times over the years. I’ve seen it progress. I’ve seen it change. But I can’t help it. When I go back there, I still feel like I’m like 14 or 15 years old. That feeling of self-consciousness never seems to go away.

definitely gone back plenty of times over the years. I’ve seen it progress. I’ve seen it change. But I can’t help it. When I go back there, I still feel like I’m like 14 or 15 years old. That feeling of self-consciousness never seems to go away.

PHAWKER: Have you had much exposure to the artistic scene there over time? Do you think it’s grown a lot since you grew up there?

AMY RIGBY: It sounds like there’s a big writing scene there now, and some great bookstores. Musically, I don’t really know as much because I was never part of a music scene in Pittsburgh. I left when I was too young to be involved in going to shows or anything. The drinking age in New York when I moved there was 18, and in Pennsylvania it was still 21. So I think that age difference had a big impact on there not being as much of the live music scene as there was in New York. I think that that really made a difference. But now, I know that there’s a lot of cool stuff going on in Pittsburgh with food and writing and craft beer. And I’m sure there’s been growth in other realms of art and music there too.

PHAWKER: The more I listen to your music, and especially your solo stuff, I feel like I can hear a lot of your Pittsburgh roots in how down-to-earth it is. Obviously, I can really hear the New York ’80s vibe too, especially in the guitar work. But why do you think this Pittsburgh sound remained in your music even though you got a lot of your formative creative years were in New York?

AMY RIGBY: Yeah, I think that’s really a great take on it. I think if you come from the Midwest – even though Pittsburgh is still slightly east of the Midwest – you grow up with this no nonsense vibe. You can’t be pretentious if you come from these places because it’s just not that kind of environment. People are plain-spoken and very self-effacing. And during the years when I was living in Pittsburgh, we’d go to see music at these epic arena shows at the Civic Arena, which is gone now, and the Three Rivers Stadium, which is also gone now [laughing]. But they were these big classic rock shows, and they were what I had to inspire me and interest me in music. Going to see Elton John or David Bowie at the Civic Arena, going to see Pink Floyd at Three Rivers. I actually didn’t discover country music until I was actually living in  New York City, even though Pittsburgh was so close to West Virginia. I think I probably went out of my way to avoid country music when I was growing up [laughing]. But later on, I think country songwriting was like a huge inspiration to me as a writer.

New York City, even though Pittsburgh was so close to West Virginia. I think I probably went out of my way to avoid country music when I was growing up [laughing]. But later on, I think country songwriting was like a huge inspiration to me as a writer.

PHAWKER: Your songs definitely have a storytelling element to them. Your writing style in this memoir reminded me a lot of the way your songs are written too. Is this your first big effort in longform storytelling? It seems to come so naturally to you.

AMY RIGBY: Yeah, I definitely undertook writing a full-length memoir before I really had any experience publishing shorter pieces. And in trying to learn to write, I would practice by writing in a blog. But to sustain that for the length of a book was very much a learning experience. But I felt like I did at least have the experience of writing songs, and knowing how to get some detail and rhythm in there. So, I think that it definitely gave me some tools to get going with writing the book, but it’s a lot harder than writing songs. It really was. Because with songs, you have the whole history of popular music helping you. People will hear references to other songs in certain rhythms or melodies or chords and harmonies, and those can do some of the work for you in telling a listener what you’re trying to say. The lyrics really fill in the story, whereas with writing, all you’ve got are those words, so that was a challenge.

PHAWKER: You’ve mentioned that part of your motivation in writing this book was that you felt a need to write yourself into the history of this time and place in music. Why do you think you might not have been part of it otherwise?

AMY RIGBY: I don’t know. Probably because I didn’t sell enough records. People will go and read about Riot Grrrls like Liz Phair or PJ Harvey. There’s a lot of artists that did great things that probably have more notoriety than what I did. I also feel like the scene that I was a part of was more low-key and more underground, partially because it was a pre-Internet time. So if you were on, say Matador Records in the early 90s — like my one band The Shams were — there hardly exists any evidence that we did anything, because there weren’t people filming shows. There weren’t people taking pictures of every show. So it’s easy to let a lot of that era just disappear. And then, as I started to make solo records, it was kind of the same thing. A record that had a ton of press in the mid 90s wouldn’t have that press on the internet. So if you don’t kind of tell people what you did and that you were there, there’s a good chance it could just get lost. I’ve been working in a bookstore for the last eight years, and I would see people pick up Patti Smith’s book and go like, “Oh, yeah, she’s actually a musician too.” And so I started to think of writing a book as a way to find people who like words and like stories, but might not be able to keep up  with music that much. And maybe if they read my books, they might go and check out my songs too. I think that that was a big motivation for me.

with music that much. And maybe if they read my books, they might go and check out my songs too. I think that that was a big motivation for me.

PHAWKER: There definitely seems to have been a lot of female-written rock memoirs in the past 10 years or so.

AMY RIGBY: Yeah, there’s definitely way more now than there were 10 years ago. And that’s really because of Patti. I think her first book, Just Kids, came out in 2010. I think that really helped open the floodgates.

PHAWKER: Right, and I’ve tried to keep up with a lot of them, like Viv Albertine’s or Kim Gordon’s or Patti Smith’s, and now, of course, yours. I’ve started to notice an interesting common theme, a lot of them talk about different relationships with guys at the time who seemed like they kind of dominated the scene even when they could be really toxic characters. But there was a temptation to be around them. Do you think that was something that was unique to the arts and music scene of the time or if it was just the cliched bad-guy interest that we all get at some point in our lives?

AMY RIGBY: Yeah, that’s a good question. I think those kinds of characters, at least in music world, were super compelling. Maybe this is unique to something creative, but they would have this daring quality that was very attractive. If you wanted to make a mark and create something, you kind of wished you could be that asshole in a way. You wished that you could be that brave to not care if anyone was watching. In my generation, at least, you were brought up to be a people pleaser and to try to keep everybody happy. So you look at these bad boys, and just think, “I wish I could just not care what anybody thinks of me and do work that stands out and grabs people.” I don’t know if that would be the case if you were in some other line of work. But people who take risks and take chances like that, that had a real appeal, and most of them happened to be male.

PHAWKER: I noticed that another theme of the book relating to you trying to break free of these norms was your use of makeup and fashion, and I really loved that. How did these aspects of your physical appearance help you achieve the kind of rebelliousness and sense of not caring that you were trying to find?

AMY RIGBY: I think back in the pre-MTV days, people outside of big cities would be really shocked by major differences in your appearance. You’d walk into a restaurant, and the whole place would just turn and stare and start saying, “Look at those freaks.” I think people became aware of different ways of dressing and looking as MTV brought that into everybody’s living room. I think that kind of self  expression was a kind of accessible way to make a statement without having to actually achieve anything. You could slather on all this dark eyeliner and look like you were interesting. It was also a little bit of a secret language with other people who were into the same things that you might be into. Maybe they had heard the Sex Pistols, too. And so they went out of their way to look different from the other people in their town and try to stand out.

expression was a kind of accessible way to make a statement without having to actually achieve anything. You could slather on all this dark eyeliner and look like you were interesting. It was also a little bit of a secret language with other people who were into the same things that you might be into. Maybe they had heard the Sex Pistols, too. And so they went out of their way to look different from the other people in their town and try to stand out.

PHAWKER: I almost got this sense in the book that while you were still going home for breaks and for the summer from school in New York, that you felt like you had a double life. Even though it seems like you grew closer with some of your family members over time, it also seems like it might not have happened as much with the others. Did you feel like you were living two lives in some way? And did that make you dread the proximity of the Pittsburgh one sometimes?

AMY RIGBY: Yeah, it was interesting to write this book because I don’t think I realized until I had written about my family how happy of a family I really had. I think I always felt like I was the rebel and that I got a lot of shit. I went to New York and two of my brothers followed me there. I kind of laid the groundwork for them. But I realized that I really did still crave that kind of happy family and sort of a normal life. I realized I wanted to be a mother. And the kinds of New York things that I had heard about that actually like took a lot of money to do — like the frozen hot chocolate at Serendipity and uptown kinds of things that I’d been reading about when I was growing up. I remember thinking that sophistication like that was anti-bohemian, but it still appealed to me. I often went back and forth between the two worlds and between wanting one over the other but also not really being able to choose. I think that was a real challenge — to try to have a baby and be a mom and keep doing music.

PHAWKER: Tell me more about what it was like to be a mother on the road, especially as Hazel got older.

AMY RIGBY: Sometimes it was fun. And a lot of times it was really hard. It was fun to be able to have her there. At the time, when I was in a band with other women, everybody kind of pitched in and I didn’t feel like I was isolated. It was nice to have the support of the other two women in the band. But then as she got older and was in school, it was hard. It felt really hard to be away from home. I felt like I missed out on things and, I felt like it was my fault because I wasn’t there. But when she got a little older, I took her with me again on some tours. We did one in England and Ireland and Scotland, and she came along with me and played with me a little bit. She started developing her own interest in music and I would tell her to pick a couple of cover songs for us to play. She was really into punk at the time. So she picked a Cramps song and we did a Wire song. That was really fun. That was really a special thing.

PHAWKER: You’ve talked before about how different you felt performing alone as opposed to how you felt performing in a group. Did having Hazel around with you like that help ease those anxieties?

AMY RIGBY: I think being a mother gave me confidence. Maybe not necessarily even having her there, but it gave me a focus and confidence that I don’t think I really had before I had her. I felt almost like there was a purpose to what I was doing, and that I wasn’t just doing it for myself anymore. At first, I just wanted to accomplish something and hope to make some kind of a living. And so it like when it didn’t feel like it was all about me anymore, it made it easier to put myself out there.

PHAWKER: Like you, I was raised Catholic, and I personally have a lot of tensions  with it. But sometimes I feel like I’m missing a community. There was a part in the book where you talked about how you tried to go to church by yourself one time in New York, but it felt like there was a disconnect there, and your relationship to church was through your family. Has anything changed since then? What place does religion, or even faith, have in your life now?

with it. But sometimes I feel like I’m missing a community. There was a part in the book where you talked about how you tried to go to church by yourself one time in New York, but it felt like there was a disconnect there, and your relationship to church was through your family. Has anything changed since then? What place does religion, or even faith, have in your life now?

AMY RIGBY: That’s a really good question. I won’t say I lost my faith. I think the whole part where my mother was in an accident — that left me pretty astounded. It was catastrophic. It was tragic. And I was amazed that my father kept his faith through it all. He really leaned on his religion and got a lot of comfort from going to mass and going to church every day. But I kind of feel like it turned me away from it. I won’t say it made me cynical, but I definitely didn’t look to it ever again. It’s funny because I have not even thought about this until just this moment as you’re asking me this, but I didn’t even reflect on it when I was writing about that time with my mother. But it just seemed like that that door just was kind of closed. I remember walking by this Catholic Church on 14th Street between Avenue A and First Avenue in New York City. That was the church that I passed the most often back then, and still do. My brother still lives around the corner from there. But it just seemed like an empty shell to me. Only St. Patrick’s felt real, maybe because it’s just such a grand building. That’s the only church that really kind of felt like it held any chance of me going in there and lighting a candle once in a while. But almost more for the drama and the ceremony of it, not as much as a for a need for prayer. When I left New York, I found nature in a way that I never knew existed before because I lived in the city for so long. I think I started to find a lot of that kind of peace and a place to contemplate out in nature.