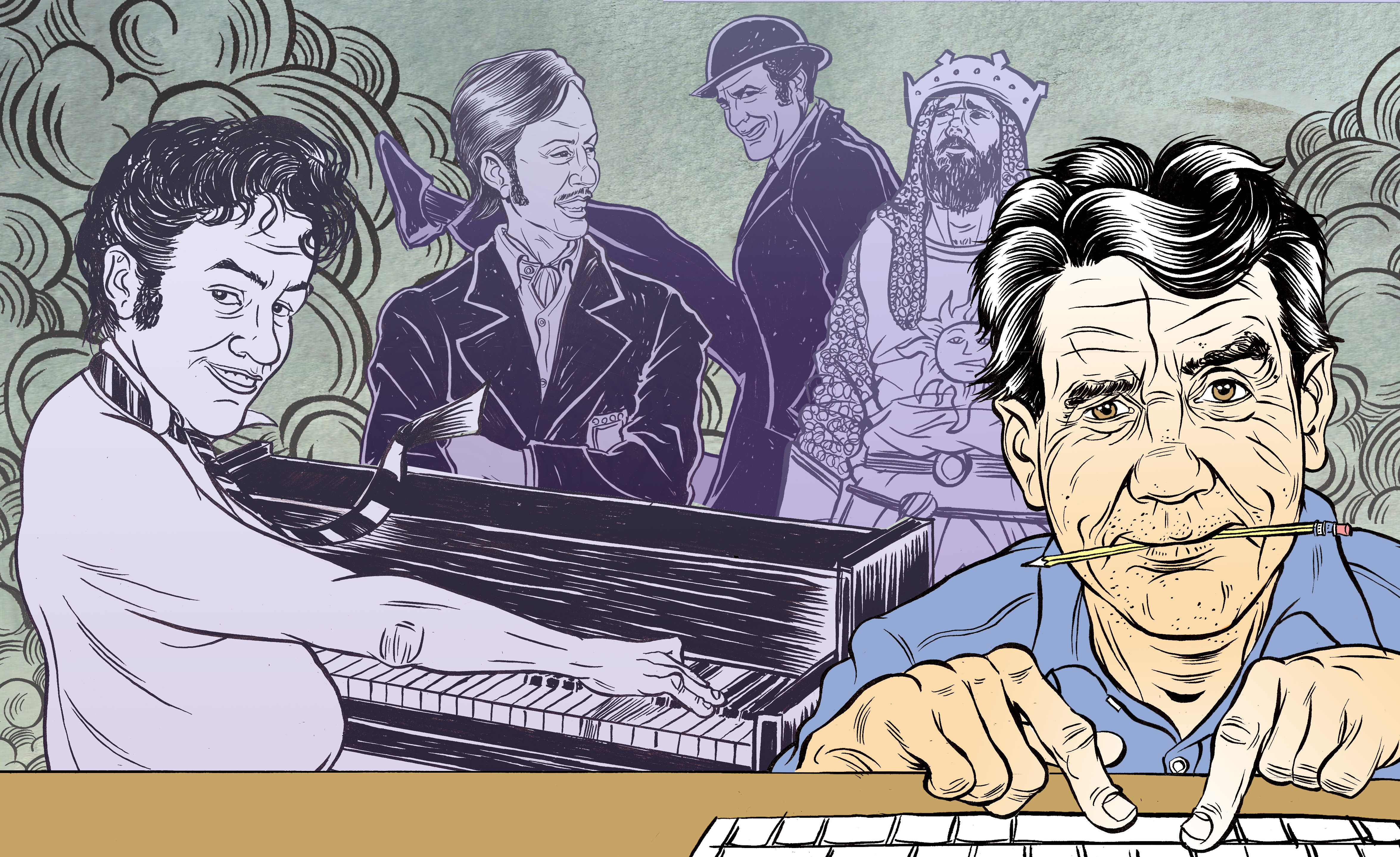

[illustration by ALEX FINE]

EDITOR’S NOTE: This interview originally posted in 2007, hence the crappy-looking overcrowded layout. We’re reprising it today to mark the sad passing of Monty Python’s Flying Circus performer/writer/creator Terry Jones. Enjoy.

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR THE INQUIRER In 1969 Michael Palin quit smoking, a pasttime he was quite fond of, through sheer will power. Having achieved a victory for mind over matter, Palin decided to raise the stakes — he would keep a diary for the next 10 years come hell or high water. What makes this enterprise interesting to people like you and me is that the decade he chose to document would also see the rise and fall and return of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. In clean, dispassionate prose spanning some 650 pages, Palin documents the trials and tribulations of the daring, off-the-wall comedy ensemble from humble-but-edgy beginnings (the name Flying Circus was foisted on the lads by the bullying BBC) to globally-recognized comedy institution (when translated for Japanese television, it became Gay Boy’s Dragon Show). A promotional tour for Diaries 1969-1979: The Python Years brings

BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR THE INQUIRER In 1969 Michael Palin quit smoking, a pasttime he was quite fond of, through sheer will power. Having achieved a victory for mind over matter, Palin decided to raise the stakes — he would keep a diary for the next 10 years come hell or high water. What makes this enterprise interesting to people like you and me is that the decade he chose to document would also see the rise and fall and return of Monty Python’s Flying Circus. In clean, dispassionate prose spanning some 650 pages, Palin documents the trials and tribulations of the daring, off-the-wall comedy ensemble from humble-but-edgy beginnings (the name Flying Circus was foisted on the lads by the bullying BBC) to globally-recognized comedy institution (when translated for Japanese television, it became Gay Boy’s Dragon Show). A promotional tour for Diaries 1969-1979: The Python Years brings Palin to the Free Library tomorrow.

Phawker: Let’s start out with a localized softball: You mention Philadelphia rather fondly in the book.

Palin: I was just looking at that. That’s the beauty of diaries — you look back in hindsight and say, “Oh I love New York, I always loved going over there” and then I read the little entry and I couldn’t wait to get out of New York and Philadelphia was like the Promised Land. The good thing about diaries is they remind you of things like that. If I hadn’t written that down I would have just carried on with this misconception that New York was more fun than Philadelphia, which clearly it wasn’t. We came to Philadelphia two or three times, I remember once, which is in the diary, we get flown in to do the Mike Douglass show and the helicopter flight from New York landed on top of a huge skyscraper, we rushed down to the studio and then back up to the helicopter and back to New York. Crazy times, not the way I’d like to travel nowadays.

back up to the helicopter and back to New York. Crazy times, not the way I’d like to travel nowadays.

Phawker: You also write in the diary that you went to the local public television station [WHYY] for a brief a 15-minute interview and it went so well you decided to do a whole special.

Palin: It was [public television who introduced Python to America] and when we went to these stations on promotional tours, it was a little like Beatlemania, albeit it on a much humbler scale. And I think we sometimes found it very difficult to play up to that. It’s one thing writing the show, but being spontaneously witty 23 times a day didn’t always work out. But I seem to remember we had a good interviewer that brought some sense out of us, as well as the nonsense.

Phawker: I was surprised to learn that the name Flying Circus was sort of foisted on you by the BBC.

Palin: Yes, we originally wanted to call it Owl Stretching Time or The Toad Elevating Moment or the Algae Banging Hour. We were determined that the show would be our own creation and that included the title. Of course, the title is very, very important. To have somebody else put a title on this mass of unconnected ideas that was Python was insulting. The BBC was very keen on Flying Circus — actually wanted to call it John Cleese’s Flying Circus. John, very wisely, was not to keen on having his name connected to a show that was untested and could be the end of his career. [laughs] So we agreed we should just make up a character and he could take all the blame if it all went badly. So I remember we all sat around one afternoon in John’s apartment off Knights Bridge. Up came the name Python as a surname. The name Mr. Python seemed very funny to us then. What will we call him? Brian Python? Eric Python? And somebody said ‘Monty’ and it for whatever reason made us laugh uproariously. So we agreed to give it the 24-hour test and see if it was as funny in the morning, and it was. So we went to the BBC and told them we wanted to call it Monty Python and they were annoyed, basically. ‘What does it mean?’ Nothing, we said. What does anything on the show mean? And so they begrudgingly agreed but with the famous last words that ‘in the future people will remember ‘Flying Circus’ but they certainly won’t remember ‘Monty Python.’

PHAWKER: And when the show aired in Japan, the title translated as “Gay Boy’s Dragon Show?”

PHAWKER: And when the show aired in Japan, the title translated as “Gay Boy’s Dragon Show?”

PALIN: Correct. Oh, the names for skits when translated were hilarious: Upper Class Twit Of The Year was translated as Aristocratic Number One Deciding Guy Show.

PHAWKER: In a sentence or two can you tell me what each of your fellow Pythons, in your estimation, brought to the table that made the show what it was?

PALIN: I’ll have a try. Terry Gilliam brought American-ness, which was very important. The rest of us were all from very similar background, all from provincial English towns and cities so he brought this trans-atlantic perspective. Terry also brought the animation, which before then had never been used like that on television show, and I think in many ways that was the key factor why Monty Python was remembered. Also it enabled us, as writers, to go from one sketch which didn’t connect to another. Very very important, helped the free form.

Terry Jones, well, it’s hard, he’s my writing partner. But he had great persistence and commitment to Python, and like Terry Gilliam, very cinematically-inclined. He wanted to be a film director since the late ’60s and that pushed Python beyond being a TV sketch show. Along with Terry Gilliam and myself, he also worked out the stream of consciousness theory of Python. John and Graham weren’t so interested in the theory, they just wanted to write funny sketches with a group of people that were sympathetic. Terry Jones understood that Python could be different and saw intellectually how it could be different.

Graham Chapman, possibly the best actor of us all and had a very manic kind of inventiveness. His mind would go in directions that nobody else I knew could or would, just all these wonderfully weird connections that brought that surreal quality. Like John, he could also play the straight man. When he plays the Colonel saying, “Stop! This is all getting silly!” You don’t think of him as a comedian doing a TV show, you believe him as a colonel telling you to stop being silly. As with John [Cleese], he had this great ability to look just like the Establishment, yet send it up completely from within.

like the Establishment, yet send it up completely from within.

John had a certain manic intensity in his performances, which I’ve not seen anywhere else except Fawlty Towers where he waves his fist at cars that don’t work and all that. Just wonderful to behold, and a very sharp writer. There’s a lot about John that you would think would disqualify him from doing comedy: this sort of intellectual legal mind and a rather serious way of looking at the world and he could turn that a few notches one way or the other and it would produce the most wonderful comedy writing. Also, and this can’t be underestimated, in comedy size is quite important. It helped in some of those sketches it helped to have two very tall men in the cast, especially when the rest of us weren’t especially tall.

Eric [Idle]? Very quick, very deft, very fast with jokes. Loved puns, loved wordplay and could play those cheeky Cockney characters — “Nudge, Nudge” being the best of those. Outside of comedy he was also the best businessmen amongst us, understood rights and deals, which the rest of us didn’t.

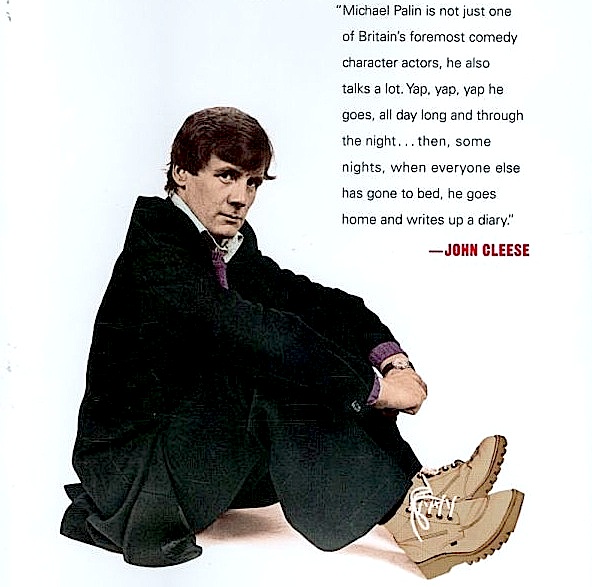

PHAWKER: Funny you should say that, if you were the Beatles I would describe you as The Sensible One. At least that’s the way you come across in the diary — a certain serenity and focus. Everybody else seems to be a little bit of a victim of their own excesses — whether it’s ego or alcohol — and you seem very centered.

PALIN: Well, maybe because it’s my diary and history is written by the winners. I avoid confrontation as much as possible, I prefer to get on with people. And I have a longer fuse than, certainly, John who used to get very irritated at things. Quite early in life I realized there were things you just couldn’t change and you were banging your fist on the wall if you tried to change the way the BBC worked or whatever. Not to say I couldn’t get upset about things as well. But I brought a certain conciliatory side to Python. There were times when nobody wanted to work with anybody else or this one didn’t want to work with that one and I just thought ‘well, I like them all so much’ and I would often act as mediator on these occasions.

PALIN: Well, maybe because it’s my diary and history is written by the winners. I avoid confrontation as much as possible, I prefer to get on with people. And I have a longer fuse than, certainly, John who used to get very irritated at things. Quite early in life I realized there were things you just couldn’t change and you were banging your fist on the wall if you tried to change the way the BBC worked or whatever. Not to say I couldn’t get upset about things as well. But I brought a certain conciliatory side to Python. There were times when nobody wanted to work with anybody else or this one didn’t want to work with that one and I just thought ‘well, I like them all so much’ and I would often act as mediator on these occasions.

There was a centrifugal force that kept Python together from the beginning. I mean, we weren’t the perfect six people to write together or anything like that, we all had different lifestyles and ways of behaving, but if you can control desire to fly out from the center, it actually created something very strong, very powerful and very funny. Because the one thing we all enjoyed was making each other laugh, so I suppose I was responsible for keeping that little group together for as long as possible.

PHAWKER: One thing that struck me was that the book covers 1969 to 1979, which is pretty much Woodstock to Studio 54, and yet there is almost no mention of drug use. I think the most tawdry thing that happens is the SNL cast sneaks into your bedroom at the Essex House for a ‘smoke.’ How is this possible? Its the ’70s!

PALIN: Well, you have to be careful what you say these days — you have to say you don’t inhale. When I was editing I would ask myself, “Do I put in that so and so did a line of coke or not?” but it didn’t happen with Python. Eric knew more people that did drugs than anyone else, but we didn’t really get involved at all. Although I think Graham smoked and we all did some marijuana. But it wasn’t central to the work and I think it’s important to say that because there are people who say ‘You guys must have been high as kites when you did this’ when in fact we weren’t and with the exception of Graham, fairly sober. If anything we used alcohol more than drugs.

was editing I would ask myself, “Do I put in that so and so did a line of coke or not?” but it didn’t happen with Python. Eric knew more people that did drugs than anyone else, but we didn’t really get involved at all. Although I think Graham smoked and we all did some marijuana. But it wasn’t central to the work and I think it’s important to say that because there are people who say ‘You guys must have been high as kites when you did this’ when in fact we weren’t and with the exception of Graham, fairly sober. If anything we used alcohol more than drugs.

PHAWKER: I was a little shocked to see how narrow the profit margins were for the Pythons in pretty much all the deals they struck. And likewise it was a little disconcerting to learn that half the Pythons were bankrupt by the end of the ’70s.

PALIN: Well, we never made a great deal from the BBC shows themselves — we were paid something like 200 pounds a week. The only money we saw was from foreign sales, specifically America when PBS bought the series, but even then it wasn’t a great deal of money. And then in 1974 when we made our first movie, nobody apart from a few rock groups were willing to back us financially. We made Holy Grail for [$400,000]. That’s just the way it was, we had a very strong and devoted fan base, but there wasn’t the big numbers that delivered a lot of money. It wasn’t until after Life Of Brian that Python offered any real financial security. And as the diaries show, everyone was off doing other things — commercials, script-doctoring, voice-overs — just to support ourselves. There’s never been crazy money in Python, it’s now coming along pretty nicely but to be honest Spamalot probably pays us more than anything else we’ve done. And that’s Eric’s show.

PHAWKER: One of the most profound passages of the diary is Terry Gilliam’s explanation for Graham Chapman’s alcoholism and how it was connected to him coming to grips with his sexuality and the courage it took to come out publicly back then. I imagine being openly gay in England in the late ’60s was a pretty tough row to hoe.

PALIN: Oh, yes. There were one or two really outrageous people who had sort of gone public, but Graham didn’t fit into that mold at all. Graham was a pipe-smoking, son-of-policeman — and of course none of these things preclude you being gay, but at the time you just wouldn’t have thought Graham was gay. I mean all his work mates and friend and Cambridge chums were, as far as I know, all sort of boring and British and straight. So it was quite a big deal that Graham declared openly that he was going to live with David [Sherlock]. I mean, you weren’t courting imprisonment as you might have five or ten years prior, but there were a lot of voices against homosexuality in the media. I think it’s mentioned in the diary that The Gay News was being prosecuted and the Pythons contributed towards their defense because we thought freedom of speech was being impinged and all that kind of stuff. But in the first instance, it was brave of Graham to do that. Because of his upbringing, he was very provincial, not London-cosmopolitan at all, and once he made that decision [to come out] it really loosened him up and he said “Now I’m going to live how I want to live.” And unfortunately he’d taken to drinking quite a bit as a doctor in training; apparently the bar was open all night at Bart’s Hospital. And it became quite excessive, really, but he was a lovely, lovely man.

PALIN: Oh, yes. There were one or two really outrageous people who had sort of gone public, but Graham didn’t fit into that mold at all. Graham was a pipe-smoking, son-of-policeman — and of course none of these things preclude you being gay, but at the time you just wouldn’t have thought Graham was gay. I mean all his work mates and friend and Cambridge chums were, as far as I know, all sort of boring and British and straight. So it was quite a big deal that Graham declared openly that he was going to live with David [Sherlock]. I mean, you weren’t courting imprisonment as you might have five or ten years prior, but there were a lot of voices against homosexuality in the media. I think it’s mentioned in the diary that The Gay News was being prosecuted and the Pythons contributed towards their defense because we thought freedom of speech was being impinged and all that kind of stuff. But in the first instance, it was brave of Graham to do that. Because of his upbringing, he was very provincial, not London-cosmopolitan at all, and once he made that decision [to come out] it really loosened him up and he said “Now I’m going to live how I want to live.” And unfortunately he’d taken to drinking quite a bit as a doctor in training; apparently the bar was open all night at Bart’s Hospital. And it became quite excessive, really, but he was a lovely, lovely man.

PHAWKER: It says on Wikipedia that the Python cast was at his side when he died, is that true?

PALIN: I was there, and John was there. I just happened to be there. He was very ill and in hospital, and I just thought, “I should go down there, it may be his last night.” And I was there with John when he died.

PHAWKER: The British are notorious for bad teeth and in the in the diary you keep a running tally in the diary of your struggles to avoid the classic “skinny English teeth.”

PALIN: It’s funny the things that wind up becoming a running theme in your life. I discovered I had some kind of periodontal condition right around the time Python was starting and so I associated that lovely time with a certain amount of pain. I’m very serious about my teeth and it was the beginning of a course of treatment that took me about 20 years. And now I know that the last thing you do is have a glass of wine after gum surgery, but in those days we just learned from our mistakes.

kind of periodontal condition right around the time Python was starting and so I associated that lovely time with a certain amount of pain. I’m very serious about my teeth and it was the beginning of a course of treatment that took me about 20 years. And now I know that the last thing you do is have a glass of wine after gum surgery, but in those days we just learned from our mistakes.

PHAWKER: Is is accurate to say that the Pythons were the de facto comedy analogue to the Beatles?

PALIN: People say that, I wouldn’t have said that myself, but oddly enough Python was much liked by rock groups, and it wasn’t just the Beatles. Led Zeppelin was one of the investors in Holy Grail. There was something about us that musicians particularly liked, maybe it was because we seemed a little dangerous, we weren’t particularly Establishment. They thought we were friends, and of course we were. And it wasn’t just George, Paul McCartney would stop recording his album just to watch Python when it first came on the telly back in 1969. Also, the Beatles broke up almost exactly the same month that the Pythons were formed, I think it was October 1969. Also in our material, there was a whimsical side as well as a hard side — there was Jones-Palin material as well as the Cleese-Chapman material, so there was a Lennon-McCartney dynamic. You give them the hard stuff, but mix it in with the surreal and the whimsical.

PHAWKER: How did the recent furor amongst fundamentalist muslims over the political cartoons in Danish newspapers compare to furor created amongst fundamentalist Christians when Life Of Brian came out?

PALIN: Well, there never was a fatwah and I don’t think we had a sense of being vilified we just knew that certain people hated what we did. And it wasn’t just Life Of Brian, there were voices in the media back then that just thought Python was subversive and irresponsible and cruel, and of course it wasn’t. Bits of it might have been, but as a whole it wasn’t. But it was a more benign atmosphere then. Now you see images of people burning copies of Danish newspapers or pictures of the Danish Prime Minister — if they can find one — in continents 7,000 miles away. I mean, nobody knew about Python in Asia. Our opposition were much more closer to home — they were churchmen, or anti-gay, or just thought we were trying to corrupt the youth of the world. And they made it clear they didn’t like what we were doing, but there were no threats. And I think now it is slightly different.

PALIN: Well, there never was a fatwah and I don’t think we had a sense of being vilified we just knew that certain people hated what we did. And it wasn’t just Life Of Brian, there were voices in the media back then that just thought Python was subversive and irresponsible and cruel, and of course it wasn’t. Bits of it might have been, but as a whole it wasn’t. But it was a more benign atmosphere then. Now you see images of people burning copies of Danish newspapers or pictures of the Danish Prime Minister — if they can find one — in continents 7,000 miles away. I mean, nobody knew about Python in Asia. Our opposition were much more closer to home — they were churchmen, or anti-gay, or just thought we were trying to corrupt the youth of the world. And they made it clear they didn’t like what we were doing, but there were no threats. And I think now it is slightly different.

PHAWKER: What is the status of Python, any chance you guys will work together again?

PALIN: No plans at the moment and I can’t really see it happening, but there are different views on this. We have always said that Python was six people writing and performing resulting in a balance which for some extraordinary reason really clicked to produce an enormously diverse range of funny material. So without Graham, it’s difficult. We could get together and write, but then to perform who plays Graham’s parts? And if you bring somebody else in immediately Python isn’t quite what it was and I’m wary of that. Everyone is doing other things and so I don’t see a Python reunion on the horizon, but you never know.