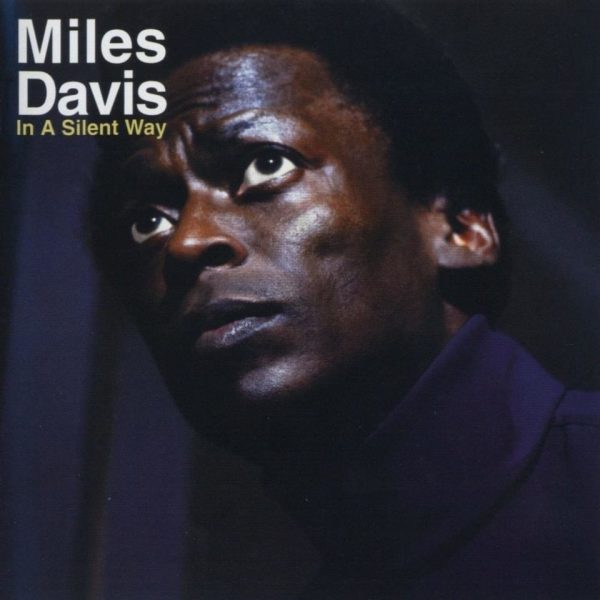

BY JONATHAN VALANIA If you don’t know Charlie Hall [pictured, below right] you should. He’s the drummer for The War On Drugs, Windsor For The Derby, co-founder of The Lindsey Buckingham Appreciation Society, leader of the a cappella choral group The Silver Ages, and an all-around good guy. A fan and a student of music in all its popular and unpopular forms, Charlie’s latest project is a tribute/cover band called Get Up With It that will mark the 50th anniversary of the 1969 release of Miles Davis’ In A Silent Way, the jazz master’s initial foray into the experimental electric/electronic music that would comprise the aural palette with which he painted for the latter part of his life and career.

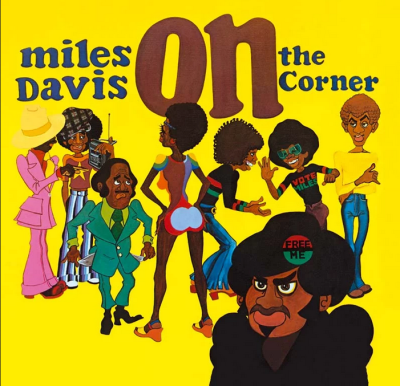

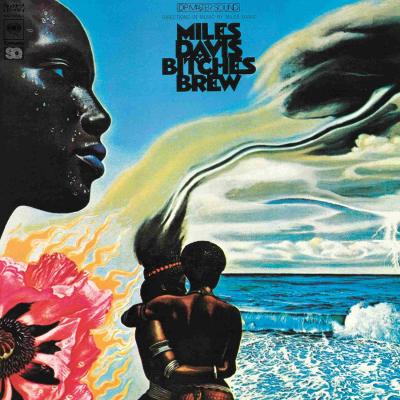

As part of Ars Nova’s October Revolution, Charlie has assembled an jazz ensemble that will perform In A Silent Way beginning to end — along with selections from key Miles Davis albums from that era, such as Bitches Brew, On The Corner and Agharta — at World Cafe Live on  Thursday October 10th at 8 pm. The band features Charlie and Brian Jones on double drums, Daniel Clarke (organ), Monnette Sudler (guitar), Ross Bellenoit (guitar), Jan Jeffries (percussion), Daniel Scholnick (tabla), Ezra Gale (bass), Mitch Marcus (Fender Rhodes and tenor), Darren Johnston (trumpet), plus special guests. Last week, I got Charlie on the horn to discuss all the above.

Thursday October 10th at 8 pm. The band features Charlie and Brian Jones on double drums, Daniel Clarke (organ), Monnette Sudler (guitar), Ross Bellenoit (guitar), Jan Jeffries (percussion), Daniel Scholnick (tabla), Ezra Gale (bass), Mitch Marcus (Fender Rhodes and tenor), Darren Johnston (trumpet), plus special guests. Last week, I got Charlie on the horn to discuss all the above.

PHAWKER: So, for people that may not know who you are, for whatever reason, let’s just start with you for a sec. What is your pedigree? When did you start playing drums? How? Why?

CHARLIE HALL: You know, I had an older brother and an older sister–nine and eleven years older than me. So, you know, I’m four, and my brother’s thirteen, it’s 1978. He’s like deep in this middle-school classic-rock phase. KISS is happening. You know, The Who, The Rolling Stones. It was just all right there. Nobody in my family played an instrument, but for whatever reason, my grandmother gave me a little Muppet Show drum-set, and I just started playing along to all his records, you know, and they started playing me a nickel to play for their friends and sing “Beth” by KISS, and stuff like that, you know, with makeup on. You know what I mean?

PHAWKER: And how old were you then?

PHAWKER: Four?

CHARLIE HALL: Yeah, this is 1978. And then, you know, my sister was into more like, sort of, new-wave stuff. So I heard The Cars, and I was just like, “Whoa. What is that? It sounded like outer space, but it was still Rock, you know? So that was like really formative stuff for me. Also, in Providence, there was a band called The Mundanes. It was kind of like a new-wave band and they would practice at their school. I think they were like, I don’t know, I think one of them taught at my brother’s school or something, I think they went to Brown. Whatever. So I would go watch them play, and I had their 45. They were great, and actually, John Linnell went on to the — he started They Might Be Giants.

The rest of them — Kevin Tooley was the drummer. That was, like, super formative for me because he, like, lived up in the attic in this party house, and it was my godfather’s house actually, but they had all these kids and they just took in strays, you know, it was one of those houses. And I’d go up to the third floor, and he had Vistalites, the kind of drums I play now. Those clear acrylic ones, and that was, like, imprinted on me, you know, when I was five years old. I was like, “Ah, this is cool. I want to play these.”

PHAWKER: So, do you have any formal training, or are you completely self-taught?

CHARLIE HALL: I’m pretty much self taught. Except for the fact that I did go to college and I did study music, but I didn’t study performing, you know, I wasn’t a performance major. I studied music history and theory, and I sort of cobbled together a track- you know, there wasn’t a music education track, but that was kind of what I- my major was sort of in music education majors, as if preparing me to like be a music teacher, so taking conducting classes and stuff like that. I just always — I loved school, you know, so I always thought I wanted to teach. But, you know, then when I got into teaching, I was like, yeah, I don’t want to be a band-leader and I don’t want to be a choir director. You know what I mean? I love talking about music and I love talking about, you know, the way music makes people feel, and how music forms people’s lives and the history of music. That stuff is really interesting to me.

PHAWKER: You grew up in Wilton, CT. And Dave Brubeck lived in your town? I’ve kind of been obsessed with Take Five lately, it’s been my first-thing-in-the-morning music all summer.

CHARLIE HALL: He sure did, yeah. All those boys. All the Brubeck clan. You know who lived down the street from the Brubecks? One Ace Frehley.

CHARLIE HALL: My mom used to take me — my special treat once a month between the ages of five and seven, when I was in my KISS phase — she would drive me down to, like, the foot of his driveway and I would, like, stare at his house.

PHAWKER: Wait. So let me get this straight. You are like five or seven years old, and Ace Frehley lived down the street?

CHARLIE HALL: Yeah. In my little town. In my small town. In Connecticut.

PHAWKER: That’s hilarious.

CHARLIE HALL: So she would take me and I would just stare, for like half an hour, just stare at his house. It was a little pond in front, but I thought it was like a goddamn moat. So I was like, “Oh, if you’re a rockstar, you have a moat around your house.” It was amazing.

PHAWKER: So, did you ever run into him in town?

CHARLIE HALL: Ace? No, Ace and my mom ran in different circles, shall we say.

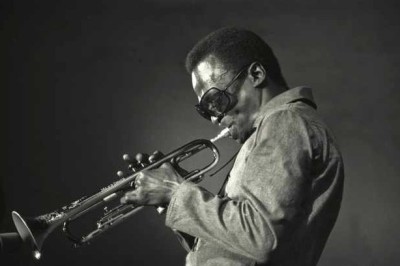

PHAWKER: So how did you get to Miles?

CHARLIE HALL: Good question. I mean, Kind of Blue. The same way everybody gets to Miles. But I don’t know. I actually don’t remember exactly how I found that, but there was a parent of a friend of mine. His name was Tim Smith. He’s recently passed but, you know, I was over at his daughter’s house, and he took an interest- he saw that I was taking an interest in jazz, you know, and I was 14, and he was like- It was like that classic thing. You know, he was like, “Hey kid.“ He gave me- he loaned me his copy of ESP of Miles Davis, which was pretty- that was pretty transformative, you know, because I was like- I was familiar with Kind of Blue and, maybe, I think I’d heard Round About Midnight, which is beautiful too, but then ESP is getting into the Wayne Shorter kinda modal zone, and that really kind of lit my Miles fire. And also, it was just a different time. It wasn’t, like, you could just immediately check everything out, you know what I mean? Also, a lot of that stuff wasn’t in print on CD. So, you know, it was like, thanks to somebody like that, like, a friend of mine’s dad, who was a jazzhead, who was like, “Hey, check this out.” He tried to set me on the right path, like before I went and started buying every Harry Connick Jr. record, or whatever. He was like, “Check this out.” Back then, there were only a handful of those Miles records that were in print, on CD. And then I remember, and I told Bruce this, I remember buying On The Corner because of the cover and I didn’t really know what I was in for. I heard On The Corner, and that was like a jolting blind lesson. And I would just keep putting it on. And I was like, “This is intense.” I had no idea what was happening. I don’t know what this music is. It sounds like someone’s doing the dishes, and it sounds like five different things happening. And then, I would put it on, like, every six months to try to understand it. And it actually took, like, hearing some of that other early seventies’ stuff to kind of really understand On The Corner, because I  think On The Corner is probably the most challenging of all that. Bitches’ Brew kind of made it all make sense, for me. You know, using the studio as a tool. You know, using editing as an instrument, not just fixing mistakes, but actually using tape edits and stuff like that as like another instrument.

think On The Corner is probably the most challenging of all that. Bitches’ Brew kind of made it all make sense, for me. You know, using the studio as a tool. You know, using editing as an instrument, not just fixing mistakes, but actually using tape edits and stuff like that as like another instrument.

PHAWKER: And, so explain to the neophyte In A Silent Way: what it sounds like, and why it matters.

CHARLIE HALL: Wow. Challenging. Obviously, there was plenty of stuff leading up to it that you can trace in Miles’ catalogue, but I think, in a way, if you zoom out and just look at his canon of music, this is kind of like the beginning of that really groundbreaking, fertile six-year period recorded right before Bitches’ Brew. It was like a three hour session one day. And I think those dudes left the studio not really knowing what they had just done. I think one of the cool things about it is that there’s three keyboard going on, that bubbling organ, which I think lends a sort of eeriness to the whole thing. There’s so much tension. One of the things I love about this record is the use of tension, without necessarily the release that you might expect. Then Miles took this three-hour session and sculpted it into this thing.

PHAWKER: So, when you guys are performing, there’s gonna be two drummers. Are there two drummers on the original recording?

CHARLIE HALL: No. Not on In A Silent Way. But, you know, we’re also going to dive into a lot of the rest of that period of music. You know, when I’m putting projects together, I’m usually playing drums, so I don’t usually have the chance to collaborate with other drummers and, so, it’s really fun for me to call my favorite drummer and be like, “Hey, are you available to do this gig?” So, I get to play with an old friend. And one of my favorite drummers in the world is Brian Jones from Richmond, VA.

PHAWKER: Yeah, let’s talk about the band.

CHARLIE HALL: Yeah, Brian is from Richmond, VA. He plays in a band called Agents of Good Roots. And he teaches at all the colleges. Brian is, like, The Dude in Virginia. He’s always been one of my drumming heroes. He’s just a few years older than me, so  I used to go see him in college a lot. You know, it sounds like he was probably brought up on metal, the way he approaches jazz. He’s got that polyrhythmic thing. He’s just a master. He can do anything.

I used to go see him in college a lot. You know, it sounds like he was probably brought up on metal, the way he approaches jazz. He’s got that polyrhythmic thing. He’s just a master. He can do anything.

So, it’s him and then my other buddy from Richmond, Daniel Clarke, who is playing the organ and he is also a supreme shredder. We’ve done some projects together before. He’s k.d. lang’s bandleader. He’s just so fun. And a natural. This is gonna be great. So those two are coming up from Virginia. We’ve got Monnette Sudler, from Philadelphia, who’s a legend. She’s part of the Sounds of Liberation movement. She played with Khan Jamal. And so, it’s so cool that I got in touch with her and she was down. So she is going to be playing guitar, along with Ross Bellenoit, who has done this with me a couple times before. Ross has a group called Muscle Tough, and he plays with Birdie Busch, and tons of people. He’s a ripper. And then, Jan Jeffries. Monnette connected me with Jan Jeffries, who’s going to play percussion. She’s from Philly, also. Amazing lady — she’s already becoming a mentor to me. And I can’t wait to play with her. And who else? And then, my crew from San Francisco is Ezra Gale on bass. And he plays in a bunch of really cool Afro-beat bands in New York, and he and I have been playing since 1996, in trios and quintets and big bands and stuff like that. Mitch Marcus on Fender Rhodes and tenor. Me, Ezra and Mitch all played in a jazz group that gigged a lot around the Bay Area when we all lived in San Francisco.

There’s Daniel Scholnick, who’s done this with us before, on tabla. And I met Daniel through a mutual friend not long after I moved to Philly actually. Really cool guy, and a really, really great tabla player. It’s not often that you get to call your buddy to play his tabla, and be like “Hey, do you wanna play this gig?” You know? So, that’s great. And then, one of the other really special things about this is that Darren Johnston, the trumpet player, who Ezra and Mitch and I started doing this with initially in San Francisco, is back. So, this is kind of a reunion of sorts for us.

PHAWKER: Very good. Okay. So how does one cover a Miles Davis song? Note for note approximation? Or is it more a loose sonic framework for exploratory improvisation?

CHARLIE HALL: Yeah, I mean, it varies from tune to tune. For me, maybe this is a drummer’s bias, but I feel like a lot of these tunes are built from a rhythmic idea. You know? So, some of these- And then, most of these tunes- There’s a motif. Like maybe it’s an eight-bar motif or something. But a lot of times, that’s the extent of the traditional head, you would call it, or melody. Sort of like, here’s a jam in E mixolydian, and it’s a James Brown groove. It’s gonna transition, then the tablas will transition us to X, Y, or Z. I made a roadmap for each tune for- like here’s the basic deal, here’s the mode, here’s the melody. And then, you know, when we get together, we’ll sort of plot out. In A Silent Way itself is a composition with a very defined melody. And there’s some important movements, like certain things that will signal another section. In A Silent Way has those really cool descending chords that signal that final section. So, you know, these are not tunes that have traditional charts. They’re built on rhythmic ideas and some version of a melody.

PHAWKER: What was the motivation for doing this project?

CHARLIE HALL: I’ve been thinking about In A Silent Way so much over the last six months and then it just occurred to me that it’s the fiftieth anniversary of it, so it just seemed like the right thing to do.

IN A SILENT WAY @ WORLD CAFE LIVE THURSDAY OCTOBER 10TH @ 8 PM