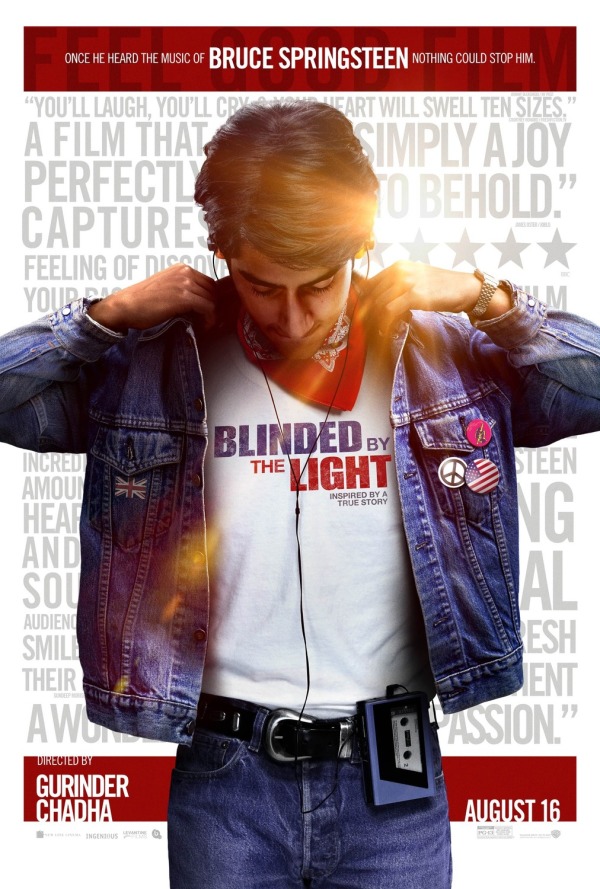

BLINDED BY THE LIGHT (Directed by Gurinder Chadha, 118 min., 2019, USA)

BY JASMIN ALVAREZ Recently, director Gurinder Chadha led a Q&A in Philly to discuss her new movie Blinded By The Light (2019) and the harrowing actuality of immigrant life during the Thatcherite ‘80s that impelled her to reimagine an upbeat and unifying cinematic alternative history. The screenplay is adapted from the memoir Greetings from Bury Park: Race, Religion, and Rock N’ Roll, written by journalist Sarfraz Manzoor, a second-generation British-Pakistani turned Springsteen-zealot who found shelter from the racist cruelties of Thatcher-fueled xenophobia in the music of The Boss. Manzoor, who co-wrote the screenplay with Chadha and her husband, joined her at the Q&A along with the film’s two starring actors—Viveik Kalra (Next of Kin), who plays Javed, the fictionalized version of Manzoor, and Aaron Phagura (Doctor Who) who plays Roops, the friend who slips him a couple of Springsteen cassettes on their second day of sixth-form college.

BY JASMIN ALVAREZ Recently, director Gurinder Chadha led a Q&A in Philly to discuss her new movie Blinded By The Light (2019) and the harrowing actuality of immigrant life during the Thatcherite ‘80s that impelled her to reimagine an upbeat and unifying cinematic alternative history. The screenplay is adapted from the memoir Greetings from Bury Park: Race, Religion, and Rock N’ Roll, written by journalist Sarfraz Manzoor, a second-generation British-Pakistani turned Springsteen-zealot who found shelter from the racist cruelties of Thatcher-fueled xenophobia in the music of The Boss. Manzoor, who co-wrote the screenplay with Chadha and her husband, joined her at the Q&A along with the film’s two starring actors—Viveik Kalra (Next of Kin), who plays Javed, the fictionalized version of Manzoor, and Aaron Phagura (Doctor Who) who plays Roops, the friend who slips him a couple of Springsteen cassettes on their second day of sixth-form college.

The tale begins in the dreary and humdrum factory-town of Luton. Javed, a Pakistani teen living in a predominantly white neighborhood, feels cloistered under the roof of his overbearing immigrant parents who prohibit him from partying or embracing English culture, confiscate his wages and allude to the prospect of his prearranged marriage. In spite of aspiring to be a professional writer, he shies away from sharing his work and chooses instead to live in the shadows—ghost-writing lyrics for his hip best-friend Matt’s (Dean-Charles Chapman, Game of Thrones) rock band. Of course, living in Thatcher’s England only adds to his angst. He is routinely spat on by skinheads while walking home and does his best to ignore the racist profanity graffiti’d onto the garages of his fellow Pakistanis.

But all that changes the night he pops a Bruce Springsteen cassette into his Walkman and presses PLAY. As “The Promised Land” comes on and Springsteen’s lyrics are plastered all across the screen, Javed’s fury — angry at politics, his parents, and the world— slowly gives way to a kind of ecstasy. Suddenly, the shackles of his parents’ subjugation and society’s contempt are shed, and he erupts — dancing fiercely in the dark.

What follows is a celebration of the transcendental power of music—exemplified by the way a white, blue-collar New Jerseyan’s song lyrics can cross the Atlantic and deeply affect and revamp the life of a young, almost-jaded Muslim teen stranded in the tiny town of Luton. The Boss becomes Javed’s permanent background music, inspiring boldness and immediate action during those moments he finds most anxiety-inducing. Hearing Springsteen’s “Prove It All Night” soon empowers Javed to kiss his crush, Eliza (Nell Williams, Game of Thrones), and “Born to Run” inspires him to cut off the sleeves of his denim jacket, Born In The USA-style. Simultaneously, he grows more confident about his own writing, passing on his poems to his English teacher (Hayley Atwell) and securing himself an internship at the local newspaper.

Not everything lands here. Blinded’s kitschy medley of coming-of-age tropes (teenage rebellion, fumbling romances, finding your tribe) does at times feel a little too on the nose and the film’s obsession with all-things-Bruce may vere into cringe-y depending on your tolerance for that kind of thing. Nor was it necessary for the lyrics of every song on the soundtrack to be spelled out and swirling across the screen for viewers to get each song’s message. And it’s kind of self-defeating that the movie’s aspiring-writer protagonist — who wants to express his own ideas and thoughts through his poetry — is constantly quoting Springsteen’s words, even in simple, everyday conversations.

Still, the film’s all-in performances (especially Viviek), kinetic pacing and pointed political commentary more or less redeem all its sins. In the film’s final act, Javed’s writing teacher secretly submits one of his poems to an academic writing competition, which wins him admission to a lit conference in New Jersey and cues up a transformational pilgrimage to the promised land of Asbury Park. What follows is a vibrant and heartwarming montage of two vastly different words colliding, which is too sweet to resist. In Javed’s absence, his overbearing father also has a change of heart and the film culminates with his family accepting his artistic endeavors and non-traditional aspirations—an ending so atypical for the era in which it is set. But that is what art does best: getting right what reality got wrong.