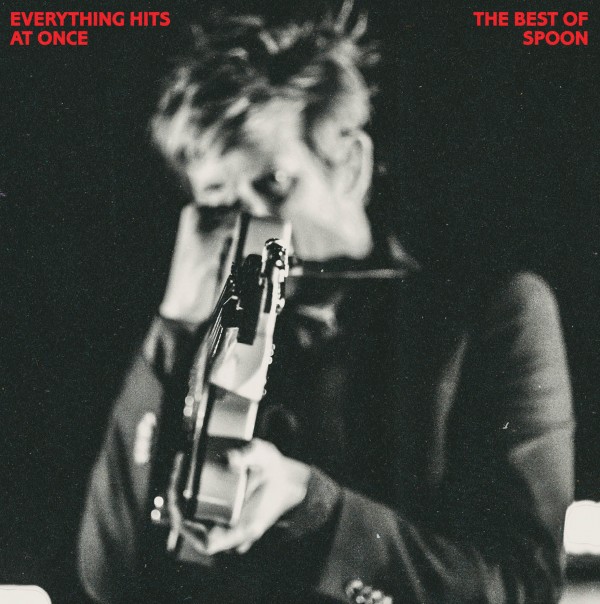

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA In the last 26 years, Spoon has gone from great white hype to major-label train wreck to “the most consistently great” band of the last decade, according to Metacritic. Algorithms can tell. They are the one band upon which we can all agree. The lion’s share of the blame and the glory rests squarely on the shoulders of singer/songwriter/guitarist Britt Daniel. Spoon is essentially a one-man band that’s had 11 members come and go or stay the course since 1993. MAGNET got all Spoon hands back on deck—not just the currently Spoon-fed, but the exiles and the mutineers, the ex-girlfriend, their first fanboy, the men who recorded their albums and the inimitable Gerard Cosloy—for this brutally honest oral history of the beast and the dragon adored.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA In the last 26 years, Spoon has gone from great white hype to major-label train wreck to “the most consistently great” band of the last decade, according to Metacritic. Algorithms can tell. They are the one band upon which we can all agree. The lion’s share of the blame and the glory rests squarely on the shoulders of singer/songwriter/guitarist Britt Daniel. Spoon is essentially a one-man band that’s had 11 members come and go or stay the course since 1993. MAGNET got all Spoon hands back on deck—not just the currently Spoon-fed, but the exiles and the mutineers, the ex-girlfriend, their first fanboy, the men who recorded their albums and the inimitable Gerard Cosloy—for this brutally honest oral history of the beast and the dragon adored.

BRITT DANIEL (Spoon singer/songwriter/guitarist, 1993-present): I grew up in Temple, Texas. Population: 45,000. There weren’t a lot of Velvet Underground fans around town. My dad was really into music, and when I was finally allowed to run the record player, that kind of sorted out a lot of boredom. But it was a long time before I was allowed to. I was in a band called the Zygotes in Temple when I was in high school. But that was mostly a cover band: lots of Doors, lots of Zeppelin, Cure and Ramones. Then I moved to Austin for school, and Skellington was the first band. I also performed and recorded solo under the name Drake Tungsten. Then there was a country/rockabilly band called Alien Beats. That’s where I met Jim.

JIM ENO (Spoon drummer, 1993-present): I only knew Britt as a bass player in this rockabilly/country band. So, he asked me to go over there and check out some of the songs he was writing, and I was pretty blown away. His songs were pop, but weird and angular, too.

ANDY MAGUIRE (Spoon bassist, 1993-1996): I answered an ad in The Austin Chronicle looking for a bass player. The band clicked very fast; we were playing out within a month. Everyone is Austin was a slacker, but Jim and Britt were willing to work very, very hard to get what they want, and that was very attractive.

JIM ENO: I think we had our very first show booked on a Friday night. We all got together Thursday night and tried to think of a name, and Britt had put on one of the cards, “Spoon,” after the Can song. I think if we would have known it was gonna stick 20 years later, we might have thought a little harder about it.

GERARD COSLOY (Matador Records co-owner): I remember my girlfriend and I were killing time between “official”  SXSW ’94 events, and stopped at the Blue Flamingo to see a more metal-ish combo that had been recommended. We saw Spoon instead. Other than making a mental note to give the charismatic vocalist plenty of shit for wearing sunglasses in a dark room, I thought they were awesome.

SXSW ’94 events, and stopped at the Blue Flamingo to see a more metal-ish combo that had been recommended. We saw Spoon instead. Other than making a mental note to give the charismatic vocalist plenty of shit for wearing sunglasses in a dark room, I thought they were awesome.

ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER (Fiery Furnaces vocalist): He used to wear sunglasses onstage because he didn’t want people to see him looking at his hands when he played guitar.

BRITT DANIEL: Eleanor was my girlfriend at the time. Anyway, getting back to Gerard — Cosloy is the kind of guy who would go see punk-rock bands play in a drag-queen bar, because that’s more interesting to him than seeing Beck, who was playing that night two doors over at Emo’s, you know? He didn’t come up to me, but someone told me that he liked us. The next year he invited us to play the Matador showcase at SXSW. And then after that happened, all these labels knew that we weren’t signed to Matador, and a couple months later we had Interscope, Geffen and Warner Bros. all trying to sign us. Which, for a band that was having difficulty getting weekend gigs in our hometown, was fucking exciting.

ANDY MAGUIRE: : It was a bit of a bidding war. They all took us to dinner.

BRITT DANIEL: I remember I ordered eggs benedict for the first time.

ANDY MAGUIRE: : Tensions were high, Britt was only 22, and it got pretty heavy—people were telling him he was a genius, and it kind of went to his head. I had more experience. I was 10 years older than him, but he didn’t want to listen to any advice, so one day they sat me down and told me they were replacing me, and I walked out. And then I got a lawsuit filed against me. They sued me for leaving the band after they fired me, and they lied and told everyone I quit. They just lied openly to their friends; even his ex-girlfriend, she said to me, “No, no, you sued him,” but she worked for a lawyer and looked it up and came back to me and said, “Oh my god, he lied to me.” Nobody really won. I mean, it killed the first album. It was a really stupid move.

JOHN CROSLIN (Spoon producer 1994–2000): The first album was recorded in my garage. Had an eight-track one-inch machine, a fairly crude set-up. But it was a blast. They were a great band for that set-up because they were pretty minimal.

BRITT DANIEL: Telephono was basically just our live show. We would just record it after work for three to four hours a night. That kind of deal. It was good, fun. It felt pro. A lot of people think it’s a picture of me on the cover but that’s Phillip Niemeyer on the cover, he was in a bunch of bands in Austin — he was just a buddy. He’s wearing, like, Dracula teeth in that photo. The title was his idea. I was always checking my messages on the phone all the time. I was like a phone guy. It was before internet. And then he crossed that with phonograph and that was Telephono.

SEAN O’NEAL (Onion A.V. Club senior editor): Freshman year of college, I started the first Spoon fan site. It was called The Sort Of Official Spoon Web Page, and it was hosted on a school server and had this mile-long URL with like a million tildes, so it was impossible to find.

ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER: I remember Britt and I took a trip to New York together and went to the Matador office, and he was very nervous about that. He loved that label; it was the epitome of cool at the time, and he was very nervous about living up to that. I remember him getting a margarita on Broadway at some Mexican place downstairs from the Matador office to steel himself before we went up.

BRITT DANIEL: I loved Gerard and loved (Matador co-owner) Chris (Lombardi), and they were putting out all my favorite bands’ records, and I thought, if we could get to be half as big as Pavement or Guided By Voices, I will be very, very happy, and things will work out in the end. Even though that record sold, like, less than 2,000 copies in its first year and was deemed very much by us and by the label as a failure, I think it was a good move.

JIM ENO: I think it was closer to 1,300, I think I found a SoundScan from the year after it came out. I think it was about 1,300. That blows my mind now—to be out on Matador and only sell 1,300 copies. And we toured a lot on that record, too. We did two tours with Guided By Voices.

BRITT DANIEL: Yeah, we did so many tours on that first record. I don’t know what the people who managed and booked us thought, but they were sending us through North Dakota, Mississippi, Alabama. It fucking sucked. It was not a fun experience. A lot of shitty nights opening for really shitty metal bands. We played for the bartenders many, many times.

JOHN CROSLIN: I filled in on bass for a few tours after Andy left. Telephono had just come out and nobody was there to see Spoon; nobody had heard of them. Some shows there were five people in the audience.

GERARD COSLOY: They had the very dubious “next-Nirvana” tag hanging around their necks without ever asking for it. Things got kinda hype-y through no fault of theirs—and I think most sensible people were suspicious. Some writers and fans alike immediately derided them as Pixies clones (a charge that seems especially hilarious today, but at the time, did Spoon no favors). And to be very fair, it should also be said that not everyone at the record label was totally behind those guys. In those days, we employed a publicist — an otherwise very talented and insightful person — who upon being told by a journalist, “Those guys kinda suck,” would’ve been apt to say, “Yeah, I know what you mean.”

ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER: The first time I saw Spoon was in the student union at UT. I was a freshman, I think, and I wanted to see them play with my boyfriend at the time, and as he said, “Oh, they sound so much like the Pixies,” and I had never listened to the Pixies, I didn’t even know what that meant, exactly.

BRITT DANIEL: There’s always, like, one storyline about an album or about a band that everyone apes, and that was ours: Pixies rip-off. The first review that I saw for that record was in Rolling Stone, and it was two stars out of five, and it was all just about the Pixies. And that kind of set the tone for the whole thing. Yeah, that wasn’t super fun. I’m not saying it wasn’t valid, you know; I love the Pixies. The cool thing is that the next record we made, Soft Effects, is still one of my favorite ones we ever did. That’s where we finally found a little bit of an identity.

GERARD COSLOY: Soft Effects felt like a big creative leap to me—really the first time those guys started using the recording studio as an instrument—a tradition they’ve built on considerably since. But there was little reaction to speak of at the time. There was so much negativity stemming from Telephono, it was super hard to get people to give Spoon a second chance.

JOSH ZARBO (Spoon bassist 1997-2000; 2002-2007): The deal with Elektra was signed after we had recorded almost all of A Series Of Sneaks. So, that record was pretty much made with Matador in the rearview mirror and Elektra not yet happening. I think Jim Eno financed that record completely.

JIM ENO: I was basically paying for the recording, since I had the day job. Near the end, it got a little hairy. It was kind of like, “I think I’m gonna get paid back for this … hopefully.”

ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER: I don’t know why Britt never gave me credit for it, but I came up with the title, He used to drive around town because he would take these secret shortcuts everywhere. I was like ‘Your life is just a series of sneaks.’

BRITT DANIEL: Most of the major-label offers that had been around a year before were gone, but this guy, [Elektra A&R guy] Ron Laffitte, hadn’t been around the first time through, and he was really big on signing us. Matador had just done a deal with Capitol, so they wanted to keep working with us. So, we had to choose between those two. Elektra offered us a lot of money—$250,000—and we were in a lot of debt, and it was like, ‘Should we try something else with this other system that we haven’t tried or go back to the system that didn’t work, which is paying us like a fifth of the money?’ It was one of the hardest decisions I had made, certainly, at that point. But we went with Elektra.

JOSH ZARBO: I remember playing the Noise Pop Festival in San Francisco — that’s where I met Ron Laffitte for the first time. He seemed like an A&R major-label guy, and I mean that in a nice way, and I mean that in a sense like he seemed like he had his shit together and he was definitely ruling the band. I remember we were backstage and somebody from Bimbo’s came back to ask us if we needed anything, and he took out a gold AmEx card and said, “Get these boys anything that they want.” I remember he took us out to eat at a really fancy restaurant, and our tour manager at the time was wearing a hoodie with holes in it and so we’re eating at this five-star restaurant and the concierge is taking our friends moth-bitten hoodie to hang up on the gold rack. It was very strange.

JIM ENO: Weirdly, he stopped returning our calls after we signed.

JOSH ZARBO: Things seemed like they really changed—it went from this guy telling us we were the greatest ever to now kind of keeping us at arm’s length. I think that right away we saw that we weren’t a priority. After we signed, we were all in New York, and we went up to Elektra at the Time Warner building, and they took up to like the 27th floor or something, and we could kind of tell they were going to show us that they were really behind the record, but really what it was was a hastily arranged pizza party.

BRITT DANIEL: A fucking pizza party.

JOSH ZARBO: It was like, “Oh fuck, Spoon is here—let’s order 20 pizzas.” We were coming in and (Sylvia Rhone, then-president of Elektra) was like, “Where’s the pizza? Why haven’t we gotten the pizza yet?” And that’s something me and Brit used to laugh about a lot. She said to me, with like a Brooklyn accent or something, she said something like, “I think we could have a lot of fun together,” and I didn’t know what to say. I was just a 24-year-old musician, you know? I wasn’t primed for the Time Warner building and meeting CEOs and stuff.

BRITT DANIEL: One time, I actually called her because I was told, “Call Sylvia and invite her to the show in New York,” so I did. I waited on hold for … I was at a McDonald’s, like, at the pay phone calling her, like, two days before we came to New York, sitting on hold for, like, I don’t know, 10 minutes or something. She finally came on. I was like, “I just wanted to let you know that we’re playing.” She goes, “You’re on the road?” And I said, “Yeah, we’re going to be playing in New York at Brownies in two days. We’d love it if you’d come.” She goes, “Oh, I know about it,” but she didn’t come. They never released a single, they never made a video, it was never released overseas. A Series Of Sneaks sold something like 2,000 copies, and within four months of it coming out, we were dropped.

JOSH ZARBO: I was concerned that maybe the band was going to stop because I could tell that Britt was living a very meager existence in a crappy apartment. They had taken small advances from Elektra because they thought that by taking a small amount of money we would be less of a liability to the label. I was concerned that maybe Britt was just not going to want to do it anymore. But then out of that is what kind of inspired him to start writing the songs that he wrote that became Girls Can Tell.

BRITT DANIEL: I felt like we were tainted goods, basically. And I guess we were. But for some reason, I didn’t stop writing songs.

MIKE MCCARTHY (producer, Girls Can Tell): I ran into Britt up there in Williamsburg. He said that he and Jim had bought an eight-track tape recorder, and had started a few recordings on their own, and would I be interested in coming down to Austin to work on music with them, to which I said, “Yes, I just need to be able to afford to do it.” So, they agree to pay my monthly child-support payment for a month to go down there and help them record, and that’s what became Girls Can Tell.

BRITT DANIEL: I felt that I was turning a corner stylistically. I was listening to a lot of oldies radio, and Elvis Costello. I started smoking pot for the first time. Maybe that had something to do with it.

JOSH ZARBO: It was less about Wire and Gang Of Four and more about Rubber Soul or Revolver or the Kinks. I remember Britt saying in MAGNET at the time that he started writing songs for himself during that time.

BRITT DANIEL: The title is a Crystals song. At that time, I was really into the idea of trying to make an old R&B kind of record. So, I was just looking through titles and liked that one. It seemed mysterious. Eleanor didn’t like that title, though. She said I was going to get backlash for it. I think she thought that I was saying, like, “Girls can tell that I have a big dick.”

ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER: [Laughs] I really don’t remember thinking it had anything to do with anything as vulgar as that. But if I did, I wouldn’t admit it now. I can remember just not liking “Girls” in the title. It seemed a little insulting.

BRITT DANIEL: I was living in New York, working temp jobs, and I remember taking my lunch break to go over to the Marriott to use their phone bank, because there was a quiet place where I could talk on the phone, calling my manager and lawyer. We would have a talk every week about shopping the album around, and every week it was the same thing—like, nobody is biting.

ROMAN KUEBLER (Spoon bassist, 2000-2002): Britt was always circling his tape around—and people were hearing it. Lots of people were hearing Girls Can Tell before it came out because we played CMJ in 2000, and there had to be 100 people there who knew all the words. I certainly remember (Merge Records co-owner) Mac (McCaughan) saying something about how he noticed how many people singing the words to an album that has not been released.

BRITT DANIEL: The record came out on Merge, and there was a story about Spoon for the first time that people wanted to talk about. Camden Joy wrote this great piece in the Village Voice that sort of set the tone, which was like, “This band made a great album on Elektra and they were dropped immediately. What is wrong with the music industry?” And then add to that that we wrote this single about it—“The Agony Of Laffitte”/“Laffitte Don’t Fail Me Now”—and it was just, like, this fucking story that’s ready to go and everybody wanted to write about, and for the first time, things started kind of happening. The first week, Girls Can Tell sold 1,200 copies, and the record before it sold 2,000 copies in a year, I was, like … I teared up. It was, like, I’m finally doing something right. Within the first year, it sold maybe 15-20,000.

JIM ENO: I remember the day the record came out; we got a little NPR thing that happened on the radio. We were driving around in the tour van, and I think we may have stopped in order to listen to it. That was unbelievable, to be able to hear people talking about our record on NPR. We had a show at the Bowery Ballroom, and I remember that every day on tour we were getting ticket-sales numbers. Every day they were increasing and increasing. We got to Chicago and we were like, “Oh my god, we just sold out the Bowery Ballroom. I can’t believe it.” Then, they added the night after, and we sold out that night, too. That was huge. Up to that point, we’d been playing in front of 60 people or so.

JOSH ZARBO: I quit before the album even came out because I was very frustrated about working with Britt. It was very difficult always for me, from day one, to be in that band. As much as I love those guys, and as much as I learned from them and the many great times I had with them, it was very difficult to work with Britt.

BRITT DANIEL: I think the real issue is that Josh and I aren’t good at being in a band together, and we’ve broken up … it’s one of those things, like a boyfriend, girlfriend that get together, break up, then they realize how much they love each other, so they try again and they realize, “Oh, this just doesn’t work.” And we’ve done that three times.

JOSH ZARBO: It was about trust and acceptance. I was never looking to take over that band or write songs or anything like that. There was something about me as a person and the kind of musician that I was that was difficult for him. I just think he thought I wasn’t cool enough or something. Which is fine, but it was very difficult to deal with. It went beyond just creatively trying to block me; he would get into personal things with me about the way I talked, the way I walked, how I was onstage, whether I played onstage with my eyes closed or open, how I moved, what I wore. It all escalated over the years of working with him where I just felt like it difficult for me to know whether to move left or right because I was so self-conscious about working with that guy. We actually had an email exchange about whether or not I could grow a beard. If I was going to grow a beard, he wanted it to look like Paul McCartney’s from the Let It Be era.

BRITT DANIEL: We just have different ideas of what it means to be in a rock band, and what that entails, and what’s cool about being in a rock band, and what bass players do on rock records, that kind of thing. Like, just a matter of playing with a pick versus not playing with a pick. I say with a pick. Because I want it to have some chunk and some aggression. Josh liked to use his fingers.

ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER: Britt’s one of those people who’s not good at relationships. He doesn’t have a family; Spoon is his life, and he’s really good at it.

JOSH ZARBO: At the same time he could be very sweet and kind. I remember at that Seattle show he announced that it was my last show and after the last chord he played on stage at the end of a show in front of 6,000 people he laid down his guitar and he gave me a humongous hug.

BRITT DANIEL: Josh and I are in touch now. We’re good buddies, and I love that dude, but we’re just not good at being in a band together.

ERIC HARVEY (Spoon keyboard, guitar, percussion, backing vocals, 2004-present): There are some bands where, if you have five of their records, chances are the same people are playing the same instruments on all of those records. Spoon is definitely not one of those bands.

ROMAN KUEBLER: The low point for me was when we did a weekend in Las Vegas. It was a really isolating experience. I remember really not having any money at the time and getting a cab to the strip was $25 and stuff like that. And it was 108 degrees out, so I couldn’t really go outside, I went out one time and it was just unbearable. I think for about two days I sat in the hotel room and then showed up for sound check, went back to the hotel room, ate at the buffet at least three times a day, and we played the shows which were extremely boring because there were very few people there, it was a casino. That was one of the last things I did with them. It was pretty brutal, I hated it.

BRITT DANIEL: We didn’t tour a lot for Girls Can Tell. My idea was, “Let’s strike now while the iron’s hot.” I went up to New London, Conn., and wrote (the songs that became Kill The Moonlight) in solitude. I wanted to go somewhere that wasn’t hot, and Eleanor lived in New York, and things were still kind of on/off with her. And I just wrote every day, and was in solitude. I listened to that Clientele record, Suburban Light, constantly.

MIKE MCCARTHY: He was really coming into his own by this point. You can hear the way with his guitar sound—that janky “jank jank jank jank” thing, and the bass would go “boom boom boom.” It’s all angular, jagged kind of playing. Even the keyboard parts. He’s very insistent. When he plays a piano—I don’t know how familiar you are with piano, but there are pedals on a piano that give you sustain or not. And he will not ever play with the sustain pedal. He’s like, “I’m not doing that. It sounds too luscious, and lush, and slick.” Back then, I think that Britt really would work closely with me, and we agreed on a lot of stuff, you know? Later on, I think he wanted to do what he wanted to do and didn’t care what I thought as much anymore. I don’t mean to say that a bad thing; I just think that’s what it turned into.

JIM ENO: We were recording the hand claps for “The Way We Get By,” and he set his phone to vibrate and put it on a chair next to us. I remember as we were clapping and stomping, his phone started ringing, kept moving closer to the edge, and we were both looking at it. Right near the end the song, it falls off and makes a very loud bang. But we kept going. And if you listen to the record, you can hear his phone dropping at the 2:12 mark. We thought it was really cool when we listened to the playback, so we left it in.

MIKE MCCARTHY: I insisted that Jim and Britt play “Jonathan Fisk” together live. And I had them play it over and over until we got the most aggressive, punk take we could get. I think they actually got kind of annoyed with me, because I kept making them play it over. They got mad, and fired up, and we got a great take.

JIM ENO: I remember doing a lot of takes, and I don’t think he picked the right one. [Laughs] I thought one of the other takes was better.

BRITT DANIEL: In middle school, Jonathan Fisk [not his real name] decided that he wanted to terrorize me, beat me up. He was always challenging me to fight, and I was like, “I actually think you’re kind of funny, I don’t want to fight” [laughts]. But he was just so mean about it, so we got into some fights after school. By the time he got to high school, being the angry little metal head was not working for him any more. He became a lot more liberal, and got really into The Cure. Eventually I gave him a bottle of vodka, and we became buddies, and then years after that, he started coming to Spoon shows.

ERIC HARVEY: I ended up living in this Austin apartment complex where Britt was my neighbor. This schizophrenic guy lived in the apartment in between, and this guy would knock on our door in the middle of the night and accuse us of, like, pouring gas in his apartment and shining lights on him and all kinds of crazy stuff. Britt and I bonded over that, and compared notes on what this guy had been doing lately. This is about a year before Gimme Fiction came out.

ALEX FISCHEL (Divine Fits/Spoon guitarist/keyboardist, 2013-present): The first time I heard of Spoon was when Gimme Fiction came out. I think I was in ninth grade.

BRITT DANIEL: The album cover was the art director Sean McCabe’s idea, based on Little Red Riding Hood. It’s his girlfriend wearing a red hood. He showed me a bunch of the photos from the shoot, and I was like, “This seems very literal.” And then he found this one, and he cropped it so you couldn’t really tell what was going on. I love it. It’s my favorite Spoon cover.

MIKE MCCARTHY: Most of their records have been recorded in a piecemeal-type fashion where one part is done at a time. I don’t know if people know that. “My Mathematical Mind” was one of the only tracks I’ve ever recorded with them where it was actually a band in a room playing the track.

BRITT DANIEL: Josh Zarbo was in a heavy-metal band called Requiem, that’s where that line comes from.

JOSH ZARBO: I was in a heavy-metal band called Requiem, yes. He ended up using that band name in the lyrics for “Sister Jack.” Which I thought was great, and the guys from Requiem thought was just incredible that that band was kind of going to be set in stone to a Spoon lyric like that.

MIKE MCCARTHY: I was really surprised that “I Turn My Camera On” became as popular as it did, because to me it seemed very repetitive and simple. I thought it was such a drastic turn by that point; I wasn’t quite sure how it would be received.

BRITT DANIEL: Gimme Fiction did well. By this point, each time we put out a record, it sold twice as many as the one before. I think it probably sold about 120,000-150,000 copies.

ERIC HARVEY: I just remember the first show I played with them was at this place called Acropolis in northern Oklahoma. I was just hanging out in the alleyway afterward, and these kids come up and ask me for an autograph and hand me a copy of Kill The Moonlight to sign, and I was like, “This is my first show, and I didn’t even play on that album.” They were like “Who cares?” By the middle of that tour, we had graduated from a van to a tour bus.

ERIC HARVEY: My most distinct memory of playing Letterman for the first time was the union guys making me feel like I was always in the way. I remember Paul Shaffer complimenting me on my clothes afterward and saying, “You’re very well-dressed for a young man. I don’t see that too often anymore.” I wasn’t sure how to take that coming from Paul Shaffer.

JIM ENO: One of our worst gigs ever was in Atlanta in one of those big summer radio festivals. We were right after this band called Heavy Mojo, who were sort of like Limp Bizkit. During their set, the festival was selling plastic bottles of beer. They would drink half of it and throw the bottle at the stage. This was before we even came on. I was like, “Boy, this is gonna be bad.” Right when we started, everyone started pelting us with these bottles. I just remember looking at Britt. He was singing into the mic and moving his head like two inches left and two inches right as these bottles are coming at his head. He kept singing and everything. I remember seeing this beer come right at my head from about 50 yards away. I was just staring at it.

MIKE MCCARTHY: The working title for “The Ghost Of You Lingers” was “Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga,” because the keyboard goes ga ga ga ga ga ga ga, and that’s where the album title came from later on.

BRITT DANIEL: Why is it five Gas and not four or six? Five just sounds better. Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga. That sounds better than Ga Ga Ga Ga.

MIKE MCCARTHY: I was trying to retain the unique character of Britt’s voice, his writing style, and his playing style, no matter what instrument it is. We started bringing in (bassist) Rob (Pope) and the other guys to play on stuff, and there was a lot of interaction from the other guys on the record and trying to incorporate them in there. And then you sit back and listen, and not to … I don’t want to downplay anything anybody did, but at the end of the day, the character of Britt’s voice, writing and playing style is the gold of that band. He’s very adamant about style, you know? Like, you know, all downstrokes on the bass. No upstrokes at all. Make sure you play with a pick. Don’t play bass without a pick. When you do guitar parts, it’s all downstrokes. Things like that. If there’s something that doesn’t fit in—no matter how great it is—if it doesn’t support the vibe, if it takes away from it, then it’s not a good part. We don’t want it. And so there WAS a lot of time spent, you know, with other people doing things that wound up getting erased.

BRITT DANIEL: “The Underdog” kind of felt like a hit. It debuted at number 10 on Billboard, and so it felt like we had shit going on.

ERIC HARVEY: We were definitely playing our biggest shows; we were either headlining festivals or close to headlining festivals. The whole thing was just a step up—that was the first album where we had songs on the radio. So, that definitely brought out a lot of people.

ELEANOR FRIEDBERGER: For me, the biggest thing was when they played at Radio City Music Hall and Britt asked me to sing a couple of songs with them. That was when I realized how big a band they were.

BRITT DANIEL: The week before we played Radio City Music Hall, I was watching this cartoon where Donald Duck does a show at Radio City Music Hall, and I’m like, “That’s me. I am Donald Duck.” That just made it feel even more legendary.

ROB POPE (Spoon bassist, 2007-present): Playing SNL felt like a giant party all the time. Everyone was so happy and the staff was very cordial; it felt like they wanted us there, which was awesome. We had multiple people come up to us, and at that point it was kind of a transition period for SNL, too. I remember Fred Armisen being like, “Awesome, we’re finally getting some cool bands.” I bonded with him because I used to go see Trenchmouth at a VFW hall in Kansas City. I was like, “I know that you’re a good drummer because I use to go see Trenchmouth.” He’s like, “What? No one who’s ever been on SNL knows about Trenchmouth.”

JIM ENO: Chevy Chase was watching us during soundcheck, which was pretty insane. I had read the oral history of SNL right before. When it was over, he said something like, “You guys sound pretty good, but you’re playing in the wrong key.”

ERIC HARVEY: I remember you couldn’t quite tell if it was a compliment or not. But it was Chevy Chase, so it’s just amazing. The other funny thing that I remember about that show (is what) they do when the credits are rolling, when everyone is kind of hugging and they are all acting like they just became best friends all week long—most of the cast are just faking it, like they are just saying completely weird shit or just mumbling. That whole thing is a total put-on, but it’s kind of awesome.

BRITT DANIEL: The week that Ga Ga Ga Ga Ga came out and was, like, number 10, it felt like we were this fucking machine that was just firing on every cylinder and, like, we were playing Saturday Night Live, and we were playing these huge shows. Success beyond my wildest dreams, you know? And I remember thinking at that point, like, “I’ve done it,” you know? Like, I remember thinking that my favorite song on that record was “The Ghost Of You Lingers,” which was the weirdest one, and I decided that from now on I should just do the weirdest stuff I can think of. That’s what I want to do right now. Why do I need to prove anything else, you know? Why don’t we just try to do it a different way and see what happens?

ROB POPE: We decided to not have any bridges. We all kind of looked at each other and were like, “Fuck, man, bridges are awful. Fuck bridges. Let’s not do any bridges this record.”

ERIC HARVEY: Transference to me immediately felt like, “I’m not really hearing a radio song on here. I’m not hearing the song that everyone is going to be dancing to.” It’s definitely a fragmented sound. It’s intentional, and it’s very cool, but I think it’s hard for some people to wrap their head around.

ROB POPE: I really enjoy the record. Now it’s become, like, our ugly stepbrother for whatever reason, which it shouldn’t be.

ALEX FISCHEL: I love Transference, and I hate that people talk shit on it. I think it’s an amazing record—all dark and kind of bruising. It sounds very personal and intimate.

ERIC HARVEY: Some of the songs were really hard to play live in a way that offered the same energy as the recording.

ROB POPE: The last leg of the tour was in Europe, and I remember I only saw the sun once in like two and a half fucking weeks. That whole tour felt like an Anton Corbijn Joy Division photo shoot. That was kind of a sign. I remember being in the back of bus talking to Britt, and we were like, “What should we do next?” It was an open discussion with him saying, “Maybe we should take a break for a minute and not schedule anything.” I think it was the first time that happened in Spoon’s career, to not have anything impending on the calendar, which needed to happen.

JIM ENO: We had just been working so hard, for so long. It just got to us, you know?

ERIC HARVEY: Toward the end of the tour, I just remember Britt saying, like, “I think this band needs to go away for a while,” and it didn’t totally shock me.

BRITT DANIEL: I remember saying to everyone, like, “We’re signed up to do a year, year and a half of touring, and maybe this record just doesn’t want to do a year, year and a half.” I was drinking more. I definitely saw that pattern emerging where you drink a lot to get through the show, and then the next day you feel hung over and shitty, and then in order to feel good enough to do a show the next day, you start drinking and just keep drinking.

ERIC HARVEY: It didn’t surprise me that he would want to do side projects with other people, because a lot of Spoon stuff rides on his shoulders. For him to be able to do a project where he wasn’t the guy in the spotlight 24/7, I could see how that could be a big relief.

BRITT DANIEL: The biggest difference between Spoon and Divine Fits for me is that I’m not writing all the songs. I was feeling a little stressed at the end of Transference, feeling like this is a lot of weight I’m carrying. I would love to just be playing bass in someone else’s band. Let them carry the weight and I can still enjoy the music.

ERIC HARVEY: I always knew that Spoon would be making another record—it was just going to be a matter of time.

BRITT DANIEL: We recorded They Want My Soul at Dave Fridmann’s Tarbox Road Studios, deep in the woods in Cassadaga, N.Y., which is maybe an hour and a half from Buffalo. It’s in the middle of nowhere.

ERIC HARVEY: My hometown is an hour away from there. The idea of recording a record in the woods is very appealing to me, and whenever I read about bands who are like, “We all lived in this cabin in the woods and did a record,” I’m like, “I wish Spoon would do that, but we’re all a bunch of city slickers. It’s not gonna happen.” Careful what you wish for. Every day there was, like, three feet of snow or something.

BRITT DANIEL: We were there when the polar vortex was going on, so it was snowing, and it was intense. It felt like The Shining after like a night or two.

ERIC HARVEY: Before I showed up Jim texted me to say it felt like “The Shining” out there. I don’t think Alex had ever seen snow!

ROB POPE: It got a little weird. I showed up one day and I think Britt and Jim had been there for a few days, and I looked in the fridge and there was half a packet of hot dogs and a couple of beers, and that’s all. I was like, “Jesus Christ.” And those guys had more facial hair than I’ve ever seen on them in their entire life. I didn’t even know those guys could grow beards. I was like, “Is everything OK? What’s going on here?”

JASON DIETZ (Metacritic): We decided to highlight the top overall artists of the past 10 years … and the band topping the list was a surprise to us as well, albeit a pleasant one … Spoon may not be the most prolific band of the decade, but they were the most consistently great.

SEAN O’NEAL: There is next to no dead weight on any of their albums. It’s an incredible batting average. The one word that comes up often in Spoon reviews is “solid”—every time they release an album, it’s solid, their career is solid, their songwriting is solid. There’s no holes in it.

ROMAN KUEBLER: Britt’s got a gift with that voice and couple his great voice with being able to write great tunes and after being thrown into an adverse situation, where the music that you make has been rejected so you’re put in a position where you’ve got to innovate and you’ve got to develop, you’ve got to be better than you are, you know? Britt certainly rose to the occasion.

BRITT DANIEL: I can’t think of too many bands that have had our trajectory: The first two records are abject commercial failures, we’re basically critical pariahs, nobody liked us, and then somehow we turned it around. But I never think about the past; I’m always thinking about what I’m doing right now and what comes next. I never think about what happened in 1997 or whatever unless I’m in an interview. It hasn’t been a bad way to spend the second half of my life. It’s been a serious improvement on the first half, all told. Despite everything, I’m still obsessed with making records and otherwise being in a rock ‘n’ roll band.