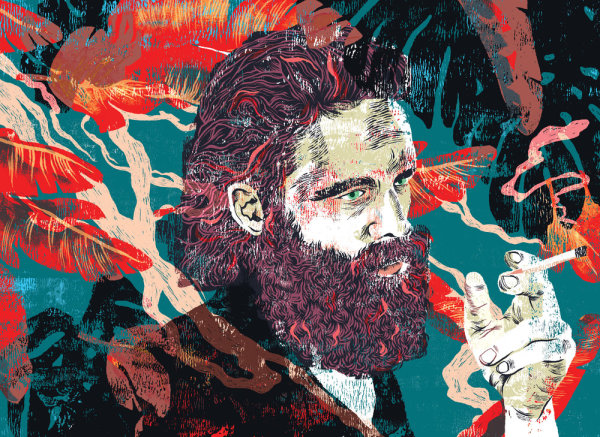

Illustration by RACHEL WADA

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the second installment of my 2013 MAGNET cover story. Part 1 is HERE.

Misty Mountain Hop

If Father John Misty’s life was a Hollywood movie, it would be a metaphysical jail-break thriller about a wrongly convicted man escaping the prison of belief thanks to the liberating power of rock ‘n’ roll and psychedelic drugs. MAGNET goes to the mountain to help write the script.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA

II

Joshua Michael Tillman is largely estranged from his family. He has contact with his parents about once a year, if at all, and it’s been that way since he left home at 18. He just turned 32, and there’s no sign of that changing any time soon, if ever. Up until he turned 18, and as far back as he can remember, he chafed under the heavy yoke of evangelical Christianity administered by his parents. “My situation at home was troubled,” he says. “I don’t really want to talk … I just never … I’ve left this out, I’m very careful to leave this out of the narrative of the music thing because it’s like, how much do you want to bring into the public square? But my situation at home was really troubled; it was a very unhappy situation underneath the suburban gleam.”

Most of his schooling was at religious institutions where the histrionics of belief were stressed over basic academics. “I have a really poor education,” he says. “I went to a Pentecostal Messianic Jewish Day School that had 30 kids, K-8. There were two people in my eighth grade class. They believe in the ‘gifts of the spirit’ as they appear in the Book of Acts: speaking in other tongues, speaking languages you don’t know, healing  people, prophecy, all that shit. They are like, that is still happening, everyone can do that, all you have to do is get baptized in fire, which is what they did to me the first day of school. Everyone in the school gathered around me and, like, put hands on me and started praying in their prayer language, which is like—if you’ve seen Jesus Camp, you know what I’m talking about. People are like [makes gibberish sounds], speaking in tongues. And that went on until I made up some gibberish sounds, which is what everyone else was doing. There was a lot of ‘slaying of the spirit,’ with kids praying over other kids, and then they would fall backwards and other kids would catch them, and they’d just be like having a seizure, which probably some of them were, like, having anxiety attacks because it was so intense.

people, prophecy, all that shit. They are like, that is still happening, everyone can do that, all you have to do is get baptized in fire, which is what they did to me the first day of school. Everyone in the school gathered around me and, like, put hands on me and started praying in their prayer language, which is like—if you’ve seen Jesus Camp, you know what I’m talking about. People are like [makes gibberish sounds], speaking in tongues. And that went on until I made up some gibberish sounds, which is what everyone else was doing. There was a lot of ‘slaying of the spirit,’ with kids praying over other kids, and then they would fall backwards and other kids would catch them, and they’d just be like having a seizure, which probably some of them were, like, having anxiety attacks because it was so intense.

“That never worked on me, and I was told it was because I was possessed by demons and that the demons had to be extracted. So, I’m walking around as, like, a fifth grader, thinking that I am like possessed by demons, and I’m like, ‘What did I do? How did this happen?’ Eventually, that turns into resentment, and for me it was like, ‘Fuck you, I’m full of demons—what the fuck are you talking about?’”

At the end of his eighth grade year, Tillman was cordially invited to never return. He got that a lot as he was growing up. His parents took him to a Christian therapist. “He diagnosed me with seasonal affective disorder and prescribed that I sit in front of a light box and read the bible for an hour every day,” he says.

When Tillman turned 11, he found a constructive way to channel his existentialist angst. “My teachers came to my parents and said, ‘Your son is hyperactive. He won’t stop tapping,’” he says. “I was constantly tapping on my desk and just running around and whatever. They’re like, ‘Maybe you need some extracurricular outlet for all this fucking energy.’ They said, ‘If we buy you a drum set, will you stop tapping at school?’”

Secular pop-culture artifacts were forbidden in the Tillman household. “It really was the McCarthy era in our house,” he says. “I didn’t see any movies that weren’t Christian, and my dad had a sign up by the TV that said … it’s like a King David quote, and it said ‘May my eyes only behold that which is holy and pure,’ or something to that effect.”

Likewise, non-Christian rock was verboten, which of course had the effect of amplifying its allure. In addition to drums, Tillman began teaching himself to play the guitar, and pecked away at the family piano, but this too was fraught with peril. “We had a piano in our living room, and I would sit at the piano and play a G chord and then a D chord, and then my mom would come tearing around the corner and accuse me of playing ‘Hey Jude,’” he says. Still, he found ways to access the forbidden. At night, he soaked up the latest alternative rock like a sponge, with the proverbial transistor radio turned low and pressed against his ear under the blankets. He befriended schoolmates he didn’t really like and mutely endured their insufferable company while availing himself of their excellent record collections.

To hear Tillman tell it, his father was Ned Flanders with a Pentagon security clearance. He is currently in the business of selling telecomm systems to repressive regimes around the globe, the kind that can be used as an internet killswitch or to pinpoint the location of dissidents for arrest and god knows what else. “He would meet with, like, generals and shit,” says Tillman. “(Tracing the location of dissidents) isn’t what it’s intended for, but it does get used for that. So, you get a lot of bang for your buck when you put in a telecommunications sytem for the people of your country all the while … just to be clear, that’s just my synopsis of it. I’m sure he would not want me to reveal that, and I’m sure it’s more complex than I am making it seem.”

His mother was the daughter of missionaries, and she spent most of her formative years in Ethiopia. She was a stay-at-home mom given to wild mood swings and sometimes scary outbursts. “This was like a severely manic parent who can’t be reasoned with, an unbelievably angry person,” he says. “And the religion thing was like putting all that anger on steroids. She was prone to really irrational outbursts—pushing and provoking me, throwing juice in my face. Having said that, she is like a really fascinating person to me the further I get from it. I very much identify with her, the pain and the despair; a lot of it I chalk up to despair on her part.”

Despair from what?

Not being loved.

Was your father like that?

No, my father had kind of a different take on despair—he really wanted all of this stuff to just not be the case.

What stuff?

The family stuff, travelling around the world and then coming home to the nightmare.

He was kind of like a passive guy?

Yeah, but I remember him intervening one time, and it was like boom! Picking [my mom] up and throwing her in another room. Talk about a primal scene, like I am being defended from my mom. Crazy.

How old were you when that happened?

That was the morning of my birthday in fifth grade, so I must have been turning … how old do people turn in fifth grade? Like 10 or 11 or something? Yeah. These things always had this really intense trajectory where it was, like, crazy anger with all the trimmings, and then intense, like, ‘I love you, I’m sorry!’ This constant kind of crazy. By the time I was in high school, I had fully emotionally disconnected from them.

In his mid-teens, Tillman started planning his escape. When he turned 18 and was legally emancipated, he would open the front door, walk the one mile to the train station and never look back. But upon graduating high school, his parents strong-armed him into enrolling at the Christian Nyack College in upstate New York.

“That was when I just really lost it,” he says. “I didn’t go to class, I slept all day and walked the streets chain-smoking all night and just didn’t see anyone. It culminated in this sort of sleep-deprived, two-day crying thing where I couldn’t stop crying and I was just thinking, like, ‘I have to get the fuck out of here. All I want to do is play music. I will move to Seattle and go fail at that.’”

And so he did.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Look for the exciting conclusion tomorrow on a Phawker near you!

FATHER JOHN MISTY PLAYS THE MET PHILLY ON SATURDAY JUNE 22ND