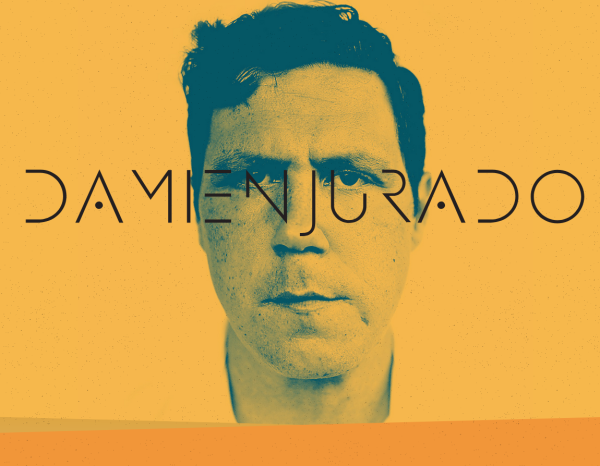

EDITOR’S NOTE: This Q&A originally published on May 18, 2018. We are reprising it now in advance of Damien Jurado’s performance at Johnny Brenda’s Friday May 17th in support of his new album, In The Shape Of The Storm.

BY BRIAN HOWARD Damien Jurado is back. That statement is more literal than figurative. With his brand new album, The Horizon Just Laughed (Secretly Canadian), Jurado—the heart-on-his-sleeve indie folker who’s spent the last two-plus decades honing his signature style of spare, probing songs that are at once hauntingly beautiful and emotionally devastating—has returned to the real world, in a way. Jurado’s three previous albums, starting with 2012’s Maraqopa, were inspired by a dream that took place in a fictional land of the same name. The Horizon Just Laughed, however takes place in much more recognizable locales, with references to familiar places like the Pacific Northwest (where Jurado had long lived)—including the ethereal heartstring-tugger “Over Rainbows and Rainier” (SEE BELOW)—and characters, including Thomas Wolfe, Percy Faith and Ray Conniff. But lovers of Jurado’s strange, alternate-reality wanderings need not fear that Jurado’s just playing it straight. The singer reveals that this album, too, has been inspired by a dream. It features some Billy Pilgrim/Quantum Leap-style time hopping—and deeply Freudian signals about the singer’s eventual move to Los Angeles, which is where Jurado was when Phawker caught up with him via phone ahead of [his May 18th] show at Johnny Brenda’s.

BY BRIAN HOWARD Damien Jurado is back. That statement is more literal than figurative. With his brand new album, The Horizon Just Laughed (Secretly Canadian), Jurado—the heart-on-his-sleeve indie folker who’s spent the last two-plus decades honing his signature style of spare, probing songs that are at once hauntingly beautiful and emotionally devastating—has returned to the real world, in a way. Jurado’s three previous albums, starting with 2012’s Maraqopa, were inspired by a dream that took place in a fictional land of the same name. The Horizon Just Laughed, however takes place in much more recognizable locales, with references to familiar places like the Pacific Northwest (where Jurado had long lived)—including the ethereal heartstring-tugger “Over Rainbows and Rainier” (SEE BELOW)—and characters, including Thomas Wolfe, Percy Faith and Ray Conniff. But lovers of Jurado’s strange, alternate-reality wanderings need not fear that Jurado’s just playing it straight. The singer reveals that this album, too, has been inspired by a dream. It features some Billy Pilgrim/Quantum Leap-style time hopping—and deeply Freudian signals about the singer’s eventual move to Los Angeles, which is where Jurado was when Phawker caught up with him via phone ahead of [his May 18th] show at Johnny Brenda’s.

DISCUSSED: Dream logic, Henry Mancini, time travel, Kurt Vonnegut, Mel’s diner, Mantovani, Chevy Chase, Percy Faith, Brian Wilson, heaven, Thomas  Wolfe, Mount Ranier, Flo, Armageddon, Tony Robbins, moving to California, moving sidewalks, Maraqopa, Ray Conniff, and trademarking the rain.

Wolfe, Mount Ranier, Flo, Armageddon, Tony Robbins, moving to California, moving sidewalks, Maraqopa, Ray Conniff, and trademarking the rain.

PHAWKER: The three albums directly preceding the brand new album were, according to the lore, inspired by a single dream. It’s my understanding that the latest album is also inspired by a dream? How does all of this dream-inspiration stuff work?

DAMIEN JURADO: The dream that inspired this new record is very much a trailer. My dreams are more like trailers, they’re not these long, drawn-out epics. How do I get a trilogy out of a trailer? I have no idea, but I did. My dreams are very snapshot-oriented—sometimes still pictures, sometimes moving pictures—just enough for me to get a grasp on the narrative, if that makes any sense to you.

PHAWKER: I’m following you so far.

DAMIEN JURADO: So, yeah. Man boards plane in nineteen fifty-whatever—or forties—and is bound for a city. He’s the last to get off the plane, and when he gets off, he realizes that he is in a different time period. So, if he takes off in 1956, he’s going to be landing in 1972. If he boards the same plane, he will go to a different location in the United States, and a different era. And he’s having conversations with people he sees on television. He’s having internal dialogue with composers he might know or actors he’s familiar with. The theme of this is that there is no home—home is over. Home is an over concept—he’s never going back. No matter how many planes he boards, no matter who he talks to, he’s never going back. And I think at this point, if this were to happen to me, I’d start to question whether I was even alive or not.

PHAWKER: Are you a Kurt Vonnegut reader?

DAMIEN JURADO: I am not a reader period. I don’t read fiction at all. [laughs]

PHAWKER: I ask because his novel Slaughterhouse-Five features a character, Billy Pilgrim, who is quote-unquote “unstuck in time,” and he hops around through different eras, which is very similar to what you were just describing. Anyway, a lot of the song titles on the record are names of people, like the composer Percy Faith and character actor Marvin Kaplan. Are these people that the protagonist of the dream is popping in on?

DAMIEN JURADO: Well, he’s not popping in on. He’s just sort of talking to them, by way of his own imagination.

PHAWKER: So based on this idea that “home is an over concept,” your song “Thomas Wolfe”… I guess that’s a pretty direct reference to the novelist who famously wrote You Can’t Go Home Again.

DAMIEN JURADO: That is actually a Chevy Chase reference from a 1970s-era Saturday Night Live bit that he did on the SNL news. And he closed out with—I don’t remember what he was even talking about—but he said, ‘Well, I guess Thomas Wolfe was right: You really cannot go home again.’ I do know that that is a Thomas Wolfe reference, but I am referencing Chevy Chase referencing Thomas Wolfe.

PHAWKER: So, I have a question that I thought sounded pretty weird, and I wasn’t sure I was going to ask it, but now that you’ve told me the album’s backstory, I’m asking it. You’ve got a song called “Marvin Kaplan,” and Marvin Kaplan was an actor best known, if he was known at all, for his role as a telephone lineman on the 1970s Linda Lavin sitcom, Alice, which was set in a suburban Phoenix diner. A character named Alice pops up in that song. In the song right after that, “Lou-Jean,” there’s an actual diner and fluorescent skies in a town called Apache, which is a ghost town in Arizona. And the next song is called “Florence-Jean,” which is the full first name of the character on that show, Flo, whose enduring contribution to pop culture is the phrase “kiss my grits.”

PHAWKER: So… is this really a three-song arc about the TV show Alice? [laughs]

DAMIEN JURADO: It is not. That is a good question. I love that you’re asking this. So, during the writing of this album, I was watching a shit-ton of television. I don’t watch modern-day TV, most of the TV I watch is from another era, anywhere from the ’50s and going on until the early ’80s; that’s where it kind of ends for me. But yeah, obviously during that period of my writing, I was watching a lot of Alice, and during my watchings of the show, I start to feel a lot of connection happening with what’s happening in my life—also to the character I’m writing about. To give you kind of a backstory, during my upbringing I was moved around from state to state continually; I never had a sense of what home was, ever. And the one thing that remained consistent throughout my childhood was that, whether I was going from Phoenix to Houston, or Houston to Seattle, the shows were consistent, and the characters were consistent. The people and the landscapes and the environment could change, but the shows were my consistency. So, there’s that influence. But during this time, I found that my mind was wandering a lot—to the pay phone inside the diner in the show. Every time it rang, I caught myself wondering if it was me calling the diner. Like some other me. Some sort of parallel-universe-me calling the diner. So, the reality was that part of me realized that this is filmed in a television studio; but there’s another side of me that is not aware of that, where it is very much a reality, and that side doesn’t want to accept the fact that what I’m watching is on a TV show, but me peering into this alternate world. Does that make any sense?

PHAWKER: Yeah.

DAMIEN JURADO: So, I began to really focus in on the extras in the background. Who was that guy getting coffee at the table? What was his name? What was his deal? What’d he do for a living? Was he married? I wonder what his house looks like. I’d go down these rabbit holes, you know. That’s kind of how the Marvin Kaplan-Alice thing took off. I started building narratives around just human episodes.

PHAWKER: Interesting.

DAMIEN JURADO: [laughs].

PHAWKER: [laughing] This interview has gotten more X-Files than I’d expected. So, is this an autobiographical album? Are you the person in this dream?

DAMIEN JURADO: Yes. I’ll say yes to the first question, and to the second, it is me. I wanna say it’s me coming from another time, but it is me. His name isn’t Damien Jurado, I don’t know what his name is.

PHAWKER: But it’s another iteration of you.

DAMIEN JURADO: On the album I reference to him by the name “Q.”

PHAWKER: The song “Over the Rainbows and Rainier” has got to be one of the most beautiful songs I’ve heard in a while. It’s also got some pretty heavy biblical themes. Is this a song about the end of the world, about Armageddon?

DAMIEN JURADO: You know, yes, in the way that it’s about ending. When I say lines like “We waited for Armageddon to go down,” Armageddon is a very loose term in my mind. It doesn’t mean biblically, it’s more that I’m talking about the shit about to go down. Now here’s what’s crazy: This album, although it was written over a year ago, ended up being very prophetic, and I still can’t wrap my brain around it. You know, the lyric “Over Rainbows and Rainier”; if you asked me two years ago, would I have ever left Washington State, I would have laughed and been like “Oh, hell no!” If you would have said a year ago, “Would you ever move to California, or anywhere else,” I’d be like “Oh, god no.” And that ended up happening, I left. I went over Rainier and I left. It’s funny. When I’ve talked about leaving to go on tour, I’ve always referred to it as “leaving the walls of the Pacific Northwest.” The mountains are pretty much like walls: the Cascades, the Olympics, Rainier, St. Helens: These are all walls to me. This song is me going over the wall.

PHAWKER: It’s almost like you knew, on some level, what was coming.

DAMIEN JURADO: I had no idea it was coming.

PHAWKER: I was thinking that “Over Rainbows and Rainier” almost sounds like a metaphor for death, or going to “Heaven.” With that in mind, there’s also a lot of bleak imagery in “The Last Great Washington State”: The building’s on fire, the sky gets turned off like a light. And you ask, “What good is living if you can’t write your ending?” It does sound very much like a goodbye.

DAMIEN JURADO: It is. And what’s crazy is that I didn’t even know it. You know, when I’m confronted with a line that says, “What good is living if you can’t write your ending,” I’m telling you, man, to even say that line, it really hits me emotionally, because I believe that’s true. Really. What the fuck is the point? There’s a line in the song: “You’re always in doubt of the truths you’re defending”? God, yeah, that is me, that was me. I always had to defend everything I was thinking or feeling. … This time last year I started watching these self-help videos, and some of these people were motivational speakers, like Tony Robbins and Les Brown. And they all have the exact same question: What is it that you want out of your life? Are you living the life that you want to live? And I just kept saying, “No, I’m not.” Now, if I’m saying no, well then what is it that you want? And even if you don’t know what you want, even if you have a smidgen of what you want, walk in that direction, and take a chance.

PHAWKER: So, you’re in California now. Was it the step you needed to take to live the life you wanted to be living?

DAMIEN JURADO: You know, that’s a very complex answer. All I can say about it is… I’ll say this: Love brought me to California. Love for my own life, for my own sanity, love for another person. Love. That’s what brought me to California, which I think is very big and powerful.

PHAWKER: Absolutely. In the song, “Percy Faith,” there’s a lot of angst about, to put it broadly, how things are and where things are going, which feels like a part of this personal journey you’re describing. You talk about rioting in the street, you talk about Seattle trademarking the rain. How people never look you in the eye, there’s no need to talk, the sidewalks walk for you. What does Percy Faith signify for you in this?

DAMIEN JURADO: This isn’t just Percy Faith. In this song, I’m talking about people like Allan Sherman, I’m talking about Ray Conniff, and these are people, in my opinion, that when we’re talking about the greats in music, we’re so quick—and honestly, it’s so cliché—even if deservedly [to worship] The Beatles, The Beach Boys, blah blah blah blah, blah blah blah blah, xyz blah blah blah, who cares? We’re not talking about innovators. And you know what’s funny? If you ask—and I know this for a fact because I’ve seen these interviews—if you talk to people like Brian Wilson, Brian Wilson will tell you, first and foremost, he is taking cues from people like Ray Conniff, like Percy Faith, like Mantovani, like Henry Mancini. It wasn’t Phil Spector. Phil Spector was of his time, no doubt about it. But, Brian Wilson was very much inspired by these very modern-day pop arrangers. And you can listen—you can put on a Ray Conniff record and be like “Oh, I get it. I now understand where the fuck he was going with Pet Sounds, or Smile, because this all makes sense now.” Now, on the flip-side of that, the commentary that I’m talking about with Seattle’s made a trademark on the rain, that’s a direct reference to Amazon. People never look you in the eye, obviously a smart phone thing. Sidewalks that walk for themselves: airports, escalators, you name it. Because of the Internet, I know everything, but yet I don’t know the guy who works at the corner store that I go to every damn day of my life.

PHAWKER: Having spent three records telling the Maraqopa story, was it liberating to make a record outside of that story arc?

DAMIEN JURADO: Yes, it was. I recently told this journalist working for the Foreign Press that it’s funny because me and the protagonist of Maraqopa have something in common, which is [that] we stayed there too long. We weren’t supposed to be there that long. I did, and it made me unhealthy. I don’t know how else to explain it, other than that I stayed there too long, so to move on, finally leave and sort of move away from that is very liberating.

PHAWKER: Why did you move around so much growing up?

DAMIEN JURADO: A lot of it, honestly, man, had to do with family circumstances. I basically had a father who wasn’t very present in my life, and a mother who wanted to chase him around the country. And during that time, neither of them could decide on a career, what the hell they wanted to do. My parents are polar opposites, but the one thing they have in common is that they are very nomadic. They love to move around, on the drop of a dime, and nothing’s going to hold them back. The trait that I pick up from them is determination. Once they decide something, good luck getting them to waver on their decision. If my mom or my dad decided, “All right. I’m moving to Arizona next week,” that’s what we did. Middle of the school year, goodbye everybody, see you later, have a nice life, see you never, you know, I’m moving to Phoenix. And then, the next year again, mid-school-year, “Hey, I’m going to go to law school in Houston.” All right, goodbye everybody, see you never, moving to Houston. And it was repeating itself over and over and over again.

PHAWKER: You were in Seattle for a good while, am I correct?

DAMIEN JURADO: Thirty-three years.

PHAWKER: Do you think that you stayed in the same place that long as a reaction to that?

DAMIEN JURADO: That’s a good question. I don’t know why. How about this for an answer: When you spend your whole life moving around all the time, you want to finally just stop. And for me, with as much moving as I did, not just from state to state, but within the state I was living—take Arizona, for instance: we lived in Surprise, then Glendale, then Phoenix. We’re going to move to Seattle, Washington, and then we’re going to move to Grays Harbor, and then we’re going to move back to Seattle. So that is basically my existence. I didn’t know it was always looking for that place to land and say, “Enough is enough. I just can’t do this shit anymore.” But I can say I’m home now.

PHAWKER: That is nice to hear.

DAMIEN JURADO: It feels good.