Artwork via SHAPERSOFTHE80S.COM

EDITOR’S NOTE: This interview originally published in January of 2016, three days after David Bowie passed off this mortal coil. We are re-posting it because it’s Philly Loves Bowie Week, duh. Holy Holy kicks off a UK tour in February, click HERE for tour dates.

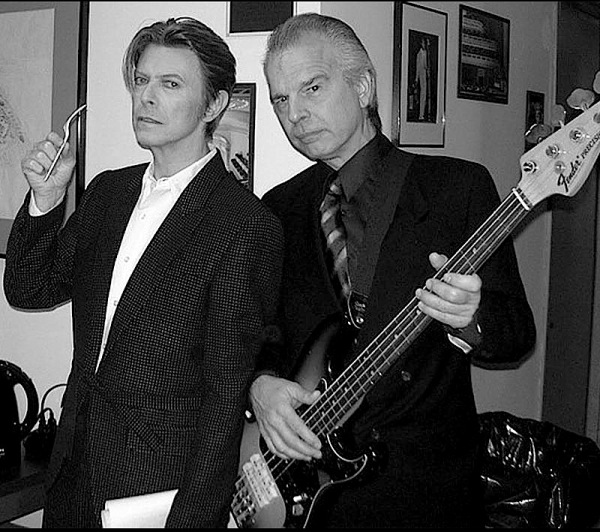

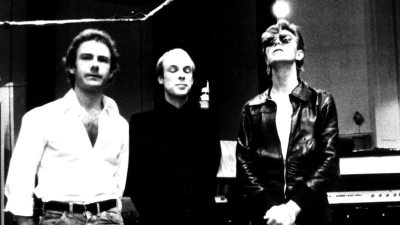

BY JONATHAN VALANIA The DJ Murray The K — the Geator With The Heater of his day — was known as the proverbial ‘Fifth Beatle’ for his tireless Fab Four boosterism during the initial waves of Beatlemania. Legendary producer Tony Visconti is the Fifth Bowie. There are others who, it could be reasonably argued, deserve the Fifth Bowie mantle, namely Brian Eno who collaborated on the vaunted Berlin Trilogy (Low, Heroes, Lodger) in the late 70s and more recently on 1995’s Outside, and Mick Ronson who from 1970’s The Man Who Sold The World to 1973’s Pin-Ups was “jamming good with Weird and Gilley” and boy could he play guitar. But Visconti is the rosebud in Bowie’s attic, recording 13 albums over the course of the last 47 years with The Thin White Duke. He was there at the very beginning (1969’s David Bowie) the middle (1975’s Young Americans through 1980’s Scary Monsters) and the very end (2013’s The Next Day and the just-released Black Star).

BY JONATHAN VALANIA The DJ Murray The K — the Geator With The Heater of his day — was known as the proverbial ‘Fifth Beatle’ for his tireless Fab Four boosterism during the initial waves of Beatlemania. Legendary producer Tony Visconti is the Fifth Bowie. There are others who, it could be reasonably argued, deserve the Fifth Bowie mantle, namely Brian Eno who collaborated on the vaunted Berlin Trilogy (Low, Heroes, Lodger) in the late 70s and more recently on 1995’s Outside, and Mick Ronson who from 1970’s The Man Who Sold The World to 1973’s Pin-Ups was “jamming good with Weird and Gilley” and boy could he play guitar. But Visconti is the rosebud in Bowie’s attic, recording 13 albums over the course of the last 47 years with The Thin White Duke. He was there at the very beginning (1969’s David Bowie) the middle (1975’s Young Americans through 1980’s Scary Monsters) and the very end (2013’s The Next Day and the just-released Black Star).

It is well-documented that Bowie habitually traded — some would say discarded — sidemen and collaborators after an album or two, always shape-shifting into someone or some thing different. The fact that Bowie called on Visconti for so many albums over so many years speaks to the depth of his trust and reliance. That alone would be enough to qualify most people for Crucial Person Of The 20th Century status. But in addition to forging all those Bowie classics, Visconti was also the architect of all those classic T. Rex albums, not to mention Iggy Pop’s The Idiot, three Thin Lizzy albums, and countless other credible works stretching back to 1968.

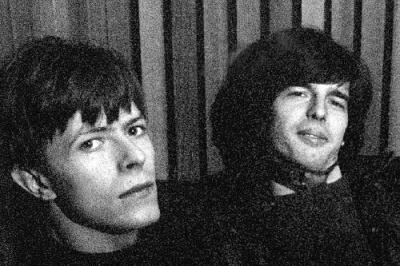

However, the album that brings us here today is Bowie’s The Man Who Sold The World, which Visconti produced, arranged, and, arguably, co-wrote, despite the fact that the songwriting credits on the album sleeve say otherwise. He also played bass on all the tracks, along with Ronson and drummer Woody Woodmansey, both of whom would go on to become Ziggy Stardust’s backing band The Spiders From Mars. Long considered one of Bowie’s lesser works, the album was largely forgotten before Nirvana covered the title track. If it sounds more like the time and the place of its making than most Bowie albums, that’s because it is the bridge between the psych-folk dabblings of late 60’s Bowie and the Brechtian glam-rock crunch of his classic early 70’s work and all that would come after. Bowie was too low on funds to promote the album with a proper tour and the album quickly vanished into the hashish mists of the early 70’s.

the tracks, along with Ronson and drummer Woody Woodmansey, both of whom would go on to become Ziggy Stardust’s backing band The Spiders From Mars. Long considered one of Bowie’s lesser works, the album was largely forgotten before Nirvana covered the title track. If it sounds more like the time and the place of its making than most Bowie albums, that’s because it is the bridge between the psych-folk dabblings of late 60’s Bowie and the Brechtian glam-rock crunch of his classic early 70’s work and all that would come after. Bowie was too low on funds to promote the album with a proper tour and the album quickly vanished into the hashish mists of the early 70’s.

Holy Holy — a new-ish group featuring Visconti on bass and Woodmansey on drums, and quietly underwritten by Bowie — is on a mission to change all that. They are currently in the midst of an American tour that stopped at the Colonial Theater in Phoenixville back in January and touches down at the Tower Theater on Saturday, April 2nd. In the wake of Bowie’s death, the concerts have become, in the words of Billboard, “strange, mad celebrations” of his life. Though the band won’t talk about it, presumably at Bowie’s behest, the tour, along with Black Star and the remarkable, next-level videos that accompany it, are all part of Bowie curating his own death. He was, after all, the man who sold the world. To be clear, the latter is all theoretical, I spoke with Visconti shortly before Christmas, three weeks before Bowie’s passing, when none of these questions were in the air.

PHAWKER: I’m a big fan of the many artists and albums that you’ve produced and it’s a huge honor to speak with you.

TONY VISCONTI: Thank you.

PHAWKER: Okay, very good. Okay so tell me, what is the impetus for doing an extended American tour performing The Man Who Sold The World with Holy Holy?

TONY VISCONTI: Well, a year ago I did four Holy Holy shows on a dare for Woody Woodmansey just to get back up on the stage and do it, and it really made me very excited to even contemplate it. But I had to put in about — I said yes — it took about three months of practicing before it even really even got up to that standard again on my bass playing. And then I went off and did the four shows and it was so exciting. I just want to do this like part of every year I want to work with Woody and his band. So I proved to myself that I still had it in me.

PHAWKER: Initially, there were four shows over in the UK. Are those the ones you’re talking about?

TONY VISCONTI: Yeah that was 2014 and then that was so successful that we went and did last year, no, this year actually, we did about 14 shows in the UK and Scotland and Ireland and then we went to Japan and did four shows so we’ve done 22 shows so far and we know it works and we know the fans love it and also the other thing Jonathan is that The Man Who Sold The World was never performed live when David Bowie was in the group. So we thought we could do it, and I mean it’s a very strong album. A dark, strong album.

PHAWKER: Yeah. Um the band is called Holy Holy which is the name of a song David Bowie recorded around the time of when the album was made, but was not on the album — in retrospect, I think it would have made a good lead-off track — can you explain why? It’s a really good song.

TONY VISCONTI: I think it was an afterthought, and we had already stopped and I was already onto my next project, so Bowie recorded that without me.

PHAWKER: Oh okay, it was recorded after the album tracks.

TONY VISCONTI: Yeah, I was working with a group called T. Rex at the time, and so I had to rush off to my next gig.

PHAWKER: A little band called T. Rex. I’m a huge fan of those records and I wish we had time to get into all of that but let’s stick to Bowie. I hope you don’t mind talking a little bit about the making of The Man Who Sold The World, and the circumstances around that time. That’s cool with you?

TONY VISCONTI: Sure, that would be great, yeah.

PHAWKER: Wikipedia suggests there are competing narratives about the making of the album and the exact provenance of the songs so I just want to read a few things back to you and tell me what you think, if that’s how you recall things or otherwise.

TONY VISCONTI: Okay.

PHAWKER: I’m quoting here: “The album was written and rehearsed at David Bowie’s home in Haddon Hall, Beckenham, an Edwardian mansion converted to a block of flats that was described by one visitor as having an ambience “like Dracula’s living room”.[6] As Bowie was preoccupied with his new wife Angie at the time, the music was largely arranged by guitarist Mick Ronson and bassist/producer Tony Visconti.[7] Although Bowie is officially credited as the composer of all music on the album, biographers such as Peter Doggett have marshalled evidence to the contrary, quoting Visconti saying “the songs were written by all four of us. We’d jam in a basement, and Bowie would just say whether he liked them or not.” In Doggett’s narrative, “The band (sometimes with Bowie contributing guitar, sometimes not) would record an instrumental track, which might or might not be based upon an original Bowie idea. Then, at the last possible moment, Bowie would reluctantly uncurl himself from the sofa on which he was lounging with his wife, and dash off a set of lyrics.” Is that accurate?

TONY VISCONTI: Um, no that’s not quite right. Okay, here’s where that idea comes from, because just a few years later when Bowie made Young Americans he was giving other band members credit for helping him write the songs like Carlos Alomar mainly but in the time when we made The Man Who Sold the World, the arrangements were considered part of the composition, part of us the song, but nowadays, since the late 70’s up until nowadays, a whole band will get credit for writing a song. I mean I think that has to be agreed amongst the members of a group too, like say if it’s the Foo Fighters or like U2 I think the whole band gets credit, and the bass player just plays the bass part. You know, so this is an earlier time where I wish we had that law in effect because I certainly would certainly have gotten songwriting credits back then back in those days, for instance on “The Man Who Sold The World” I wrote my own bass lines.

PHAWKER: Okay.

TONY VISCONTI: And Ronson wrote his own guitar line, but we didn’t write the lyrics on the melody, that is purely Bowie. So Bowie obviously wrote the songs but we did live together like a hippie Commune. People were sleeping on the floor, bringing their girlfriends back and in an apartment where we could sleep four people comfortably we had up to  about a dozen people in some instances sleeping there and sharing one bathroom I might add. I was going to say, Jonathan, to put a positive spin on it, it was a very creative time I wouldn’t be in another place if you made me it was so exciting to work under that kind of pressure and that freedom as well to go into the studio and do it. Yet David was preoccupied not only by Angie, but he’s always got other interests. For instance, he was also interested in antiques at the time, so he was going to antique dealers and buying some Art Deco pieces. But Mick Ronson and I, and Woody of course, did generate the band sound and we worked very very hard to try and keep that sound that’s why Woody and I feel very qualified to go out and represent that album now.

about a dozen people in some instances sleeping there and sharing one bathroom I might add. I was going to say, Jonathan, to put a positive spin on it, it was a very creative time I wouldn’t be in another place if you made me it was so exciting to work under that kind of pressure and that freedom as well to go into the studio and do it. Yet David was preoccupied not only by Angie, but he’s always got other interests. For instance, he was also interested in antiques at the time, so he was going to antique dealers and buying some Art Deco pieces. But Mick Ronson and I, and Woody of course, did generate the band sound and we worked very very hard to try and keep that sound that’s why Woody and I feel very qualified to go out and represent that album now.

PHAWKER: Another thing I wanted to drag out from the past is this quote from the 1976 Playboy: “Well The Man Who Sold The World is actually the most drug oriented album I’ve made, that was when I was my most fucked up. Young Americans was probably a close second but that was from my current coke period, but The Man was when I was holding up some kind of flag for hashish and as soon as I stopped using that drug I realized it dampened my imagination. End of slow drugs.” Can you speak to that at all?

TONY VISCONTI: Of course I can. Well, that’s probably something he was doing privately before we even started living together because in that apartment, as libertine as we were, with drugs, I mean I don’t remember drugs being present. We were also very very poor. We couldn’t afford drugs. So that’s something that came out of, I think prior to meeting me he went through and smoked a lot of hashish, as we all did in London in those days. But not during the making of the album. Certainly not.

PHAWKER: So there wasn’t a thick fog of hashish smoke billowing through the studio while you were recording.

TONY VISCONTI: I mean I would say so if we did, I mean I don’t mind admitting to anything but it wasn’t like that.

PHAWKER: Kurt Cobain listed the album as number 45 in his list of Top 50 favorite albums, and so I’m curious of what you think of Nirvana’s cover of The Man Who Sold The World.

TONY VISCONTI: Well I’m flattered because it’s almost a direct copy of ours. They added a cello playing the bass line, it was great. It was great. I’m a big fan of Nirvana. That was flattering.

PHAWKER: There was a mellotron used on the album that belonged to George Harrison? Is that correct?

TONY VISCONTI: Yes, because at that time there were only two mode synthesizers in the UK and George Harrison owned one and we had to hire it along with a programmer because nobody knew what the hell those knobs did. I think there were two Moog synthesizers in London at the time, and only two people in the UK who knew how to work them. We loved the sound of Switched On Bach by Walter Carlos — who later became Wendy Carlos — and we were all so turned on about that album. We loved that album. We played it incessantly and David in fact, before his concerts in those days, he would have the Walter Carlos version of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” playing loudly over the speakers before he came onstage. We do that too. Holy Holy does that too.

PHAWKER: On Space Oddity, the album before The Man Who Sold The World, you refused to produce the title song even though you produced all of the other  songs on the record. Why?

songs on the record. Why?

TONY VISCONTI: Because the album was already written and it was, you know if you know the album well, it was in the nature of folk rock. My brief to record David in those days was to get him doing one thing because he was all over the place writing Broadway musicals and folk music and all kinds of different things so I said okay, and we were all set to go into the studio to make that album when at the last minute he just stayed up late one night and wrote the “Space Oddity” which was out of the character of the album. And I thought like the rest of the songs had such deep lyrics to them and this is like really simple and it sounded a little bit like imitation Beatles, a little bit of Paul Simon, Simon and Garfunkel, and I said: “This will be a hit but it’s going to be a one hit wonder kind of job.” Anyway, I was full of hippie ideals in those days, and I have since regretted not doing that but I mean that’s where I was coming from. And you know in those days he wasn’t famous and I wasn’t famous, I hadn’t made a hit record yet and we only had about four or five days in a studio and I couldn’t mess around with this new song which the current band couldn’t play anyway. But anyway his manager said that the album is not going to go and they decided to pull the album if you don’t record the song and I said okay, well, get someone else to record it because I don’t want to do it. And I was prepared to drop the album too you know. I was too much of an idealist.

PHAWKER: Back to the The Man Who Sold The World, at the end of “Black Country Rock” David Bowie seems to be channeling Tyrannosaurus Rex, with that crazy vibrato thing that Bolan used to do. Bowie sounds like a dolphin. Reportedly Bowie was heavily influenced by Bolan at the time, can you speak to that?

TONY VISCONTI: Well they were friends from around the time they were both 14 or 15. And they were both London boys they were always bumping into each other. They always had very entrepreneurial ideas like they were both trying to dominate the fashion scene as well, you know David had his long hair, and oh my gosh what do you call it, The Long-Haired Men’s Society, he was the rocker and Marc Bolan was the Mod, but of course there was a jealous competition for a brief period. But they always respected each other musically as well so I think David simply alluded to Marc just as respect. They influenced each other it was very clear.

PHAWKER: Most people say Electric Warrior is the definitive T. Rex album but I would vote for The Slider. What do you remember about making that album?

TONY VISCONTI: Well The Slider was a very slick version of Electric Warrior. We kind of got better. Electric Warrior was kind of a little inconsistent but still one of my favorite albums. But on The Slider we really knew what we were doing. Finally. And I had been with them from the very early stages of Tyrannosaurus Rex days and both Marc and I were on this mission to make hit records. We were dying to make hit records. David Bowie was more like an art rock performer even from his earliest beginnings, we just wanted to make radio hits. And we finally did it, so I think The Slider represents the highest of our achievements during that period.

PHAWKER: Thank you for vindicating me. You just helped me win a number of bets. This is like Woody Allen getting Marshall McLuhan to help him win an argument he’s having with the pretentious guy standing behind him in line for a movie in Annie Hall.

TONY VISCONTI: *Laughs*

PHAWKER: After The Man Who Sold The World was released in 1970 you didn’t work with David Bowie again until 1974. Can you explain that gap?

TONY VISCONTI: Well we parted our ways after The Man Who Sold The World because it looked like no one appreciated what we were doing. And we released it to some critical raves about it but mostly it was ignored. So we split up. That’s why we didn’t even play the album live. Mick Ronson and Woody Woodmansey went back to the North of England where they lived for a full year before they came down and made Hunky Dory. As I said by that time I had moved on to concentrating on Marc Bolan so by then David, I mean Hunky Dory was great, one of my favorite Bowie albums. But by the time he invented Ziggy Stardust we were long parted and I didn’t really know if we were ever going to get back together again. But really that’s why we split up I mean we liked each other but we just didn’t really know if we were right for each other.

PHAWKER: The album that you did come back to work on was that you mixed the live records that was recorded here in Philadelphia, where I’m calling you from, at the Tower Theater? Were you there for those concerts?

TONY VISCONTI: Let me see, no I wasn’t. I just mixed the audio part. Actually, we got together and I mixed the album Diamond Dogs just before that. Then he recorded that with some engineer you know they just went around with a mobile and recorded a few shows. And if I did mix that show that was maybe the second thing we did together. Mixing the live show. I was in Philadelphia for the following live album called Stage. I was actually in the truck I was recording it that was my own engineering.

PHAWKER: Terrific. Well speaking of “Space Oddity” and jumping ahead to the present year, at the beginning of the video for “BlackStar” — this beautiful, bizarre, strange, this very artfully rendered video — there is a dead astronaut laying on the ground, presumably the remains of Major Tom who’s been has been quoted and referenced in Bowie songs stretching back from “Hallo Space Boy” to “Ashes To Ashes” to “Space Oddity.” Do you see any sort of connection between those older songs or the character of Major Tom in “BlackStar”? I mean is that intentional or is that just a coincidental thing?

TONY VISCONTI: I mean it could be or it could be another astronaut. That’s all I’m saying about it. I don’t know.

EDITOR’S NOTE: In hindsight, it is readily apparent that Bowie was auguring his own impending death.

PHILLY LOVES BOWIE WEEK RUNS FROM JANUARY 4TH-13TH CLICK FOR A LISTING OF EVENTS