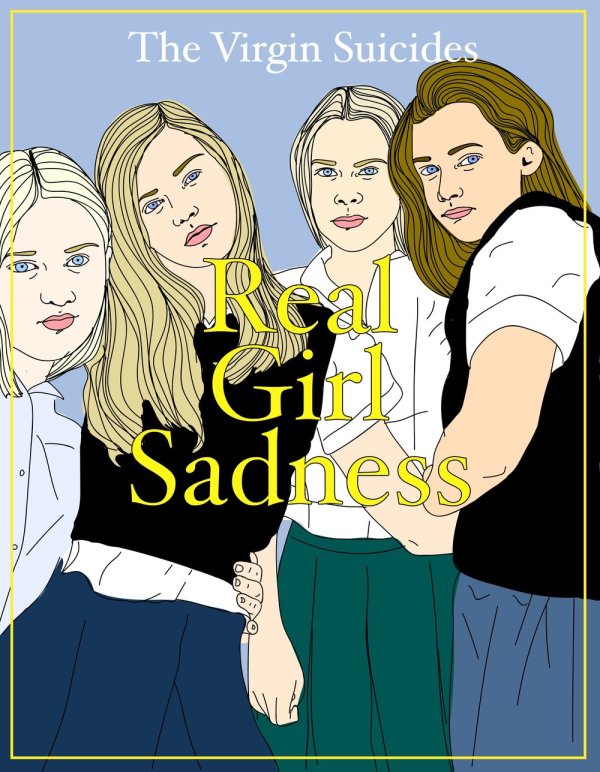

Illustration via GOLD HAND GIRLS

THE NEW YORKER: I still own the copy of “The Virgin Suicides” that I first read in high school, the evidence of my teen-age self on its pages: water-rippled from many hours in the bath, stained with juice from the tangerines I used to eat in great quantities. It’s a book I’ve read many times now, but I still remember that original encounter, how it felt like a flare from my own secret world, all the inchoate longings and obsessions of being a teen-ager somehow rendered into book form. Even the five Lisbon sisters seemed like some mirror of me and my four younger sisters—I knew the peculiarity of a household filled with girls, the feverish swapping of clothes, the rituals and ablutions, experiencing adolescence like some long-standing illness from which we all suffered. The world of “The Virgin Suicides” was gothic and mundane, just like the world of teen-agers, with our desire to catalogue and make meaning out of any sign or symbol, even the mildest of occurrences taking on great portent. It was exhausting to live that way, believing in the significance of every feeling, tracking every minor emotional shift. But still: sometimes I miss it.

“On the morning the last Lisbon daughter took her turn at suicide—it was Mary this time, and sleeping pills, like Therese—the two paramedics arrived at the house knowing exactly where the knife drawer was, and the gas oven, and the beam in the basement from which it was possible to tie a rope.” From the very first line, the reader understands the Lisbon girls—“daughters”—will all die. The paramedics can easily navigate this last attempt because what should be shocking—a young girl’s suicide—has become, in the strange logic of the Lisbon family, routine. Even the narration is measured, calm, relaying the suicide method with a simple aside. There is no crime for the reader to try to solve, no whodunnit. We know what happens. We know who dies, and how, and by what methods. By giving us this information immediately, with such cool distance, Eugenides directs our attention to different questions, to a different scale of novelistic inquiry. Even when all the unknowns become known, every detail accounted for, every witness interrogated, how much can we ever truly understand our own lives?

In one of the great feats of voice, “The Virgin Suicides” is narrated by a Greek chorus of unnamed men, looking back on their adolescence and the suicides of five girls in their Michigan suburb. The narrators are both elegiac and mordant, dipping in and out of lives, moments, acting as the collective consciousness of an entire neighborhood. The men have never quite moved on—despite their now “thinning hair and soft bellies,” they remain arrested as boys, circling around the lingering mystery of what motivated the girls’ deaths. With procedural effort, they’ve exhaustively catalogued relics from that time (“Exhibits #1 through #97”), conducted interviews with the most minor of neighborhood players, imagined themselves into the heads of the five Lisbon sisters—tried, essentially, to fully animate the past. The book retroactively constructs the eighteen months between the first daughter’s suicide and the last, while the middle-aged narrators obsessively probe a mystery that might never be revealed, the clues only half-legible. MORE