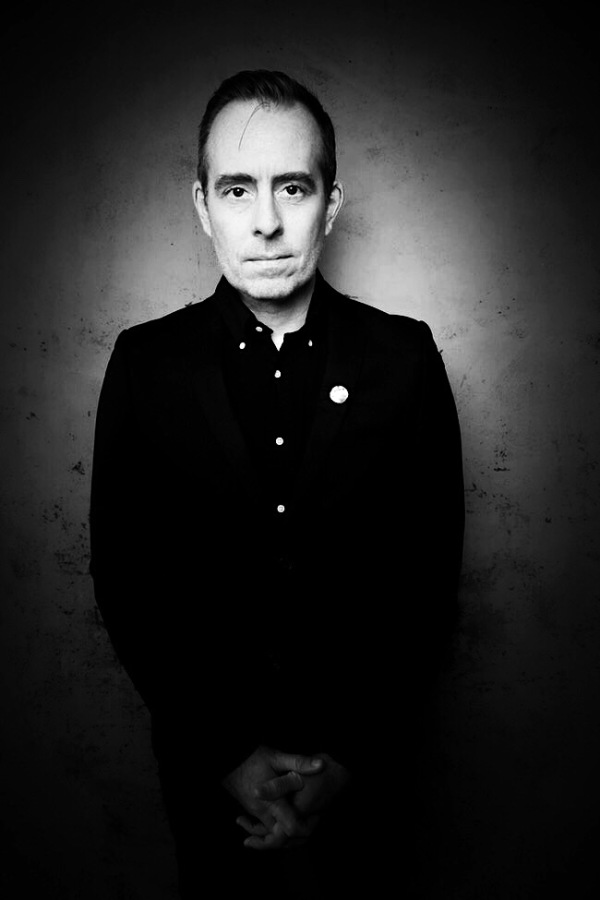

BY SOPHIE BURKHOLDER Ted Leo is a born and bred punk. He grew up in Bloomfield, New Jersey, coming of age at the peak of the 1980’s hardcore punk scene, playing in bands like Citizens Arrest, Puzzlehead, and, later, noted DC neo-mods Chisel. In 1999, having mothballed Chisel, he stepped into the spotlight with Ted Leo and the Pharmacists, cranking out seven well-received albums of high-octane, punk-edged power-pop over the course of the next decade and built a large and loyal following in the process. But somewhere around 2010 he ran smack into a brick wall of bad karma, personal struggles, diminishing record and concert ticket sales and mounting debts incurred treating his wife’s illness — and Ted Leo & The Pharmacists went on indefinite hiatus.

BY SOPHIE BURKHOLDER Ted Leo is a born and bred punk. He grew up in Bloomfield, New Jersey, coming of age at the peak of the 1980’s hardcore punk scene, playing in bands like Citizens Arrest, Puzzlehead, and, later, noted DC neo-mods Chisel. In 1999, having mothballed Chisel, he stepped into the spotlight with Ted Leo and the Pharmacists, cranking out seven well-received albums of high-octane, punk-edged power-pop over the course of the next decade and built a large and loyal following in the process. But somewhere around 2010 he ran smack into a brick wall of bad karma, personal struggles, diminishing record and concert ticket sales and mounting debts incurred treating his wife’s illness — and Ted Leo & The Pharmacists went on indefinite hiatus.

After seven years of releasing almost no new music — save a one-off LP collaboration with Aimee Mann in 2013 under the name The Both — Ted Leo came back last year with The Hanged Man, a deeply personal and emotional wrenching album that gave a new and poignant depth to the political punk rocker of the early aughts. Concurrent with the release of The Hanged Man, he went public with his struggles to overcome PTSD from abuse he suffered in his childhood, his wife’s epic and costly journey to regain her health and a prevailing sense of career entropy in a must-read in-depth story on Stereogum. Leo has spent the better part of the past year on tour – first for The Hanged Man, then in support of the 10 anniversary reissue of Hearts of Oak. He is currently in the midst of a solo tour which includes a stop at the Ardmore Music Hall on Saturday September 15. We got him on the phone to talk about the good, the bad, and the ugly of the last decade, and of course asked him to make the ultimate rock and roll choice: Beatles or Stones?

PHAWKER: You are definitely a high-octane guy, and your music is also very high-octane,  and I read somewhere that you said something about being 20 milliseconds ahead of the beat in your music and in your life, so could you just kind of explain that a little bit?

and I read somewhere that you said something about being 20 milliseconds ahead of the beat in your music and in your life, so could you just kind of explain that a little bit?

TED LEO: Well [laughing], it’s something I’ve been trying to actively combat since it was revealed in making the record that I made with Aimee Mann, but it was true while we were making that record. In mixing it we realized that every vocal that I did was consistently, exactly, 20 milliseconds ahead of the beat [laughing]. And we joke about it, but it is kind of a metaphor, I think, that is somewhat accurate of other areas of my life.

PHAWKER: You’ve talked a lot about the Clash in other interviews, which is actually interesting to me right now because I’m currently reading Viv Albertine’s first memoir. But anyway, it’s a known fact that you’re a huge fan of them, so I’m wondering what your favorite and least favorite songs are by them?

TED LEO: Hmmm, that’s interesting. I mean yeah, that was a band that I grew up with. Certainly it’s that particular kind of punk that had an influence on me, because they spoke and they sang to bigger issues. I sort of look at them as a high tide, like the kind of music that raises your eyes above your immediate surroundings to sort of think in different ways globally. I think that musically, probably what I would say, my favorite stuff would have to be either “Clamp Down” or “Death or Glory,” from the London Calling album. They’re rock songs where they were experimenting with a more danceable beat at the time, but they also have this sort of driving energy and political lyrics that are poetically expressed. That’s a template that I certainly learned, or maybe not learned, but understood when I heard.

PHAWKER: And then your least favorite song?

TED LEO: [laughing] I don’t know, I mean probably “White Riot.” Because it’s a great song in a lot of ways, but it’s a young person’s take on race relations that I think would make an older person cringe at the way of expressing it. I think the intention is in the right place, but one could possibly look back and say “Yeah, maybe I shouldn’t have written things that way.”

PHAWKER: Yeah, I read somewhere that if that exact kind of punk music came back around today, people would still be very shocked by it. But speaking of having those higher meanings, what would you say is the last thing you listened to for the first time that blew your mind or changed your perspective? Even if the answer to that is a band from the past, maybe you can also think of a band or music from right now that you think has that same vibe to it as well?

TED LEO: I think that some of the most interesting stuff that’s happening right now is non-straight-white-dude stuff. I’ve been lucky to have been able to tour over the last year with some great bands that are fronted by women. Like this band from LA called Ian Sweet, who we toured with last fall, who are making really interesting and intricate, almost like orchestrated pop, but as a three-piece. I also got to tour with Sad13, which a project from Sadie Dupuis of Speedy Ortiz. It’s really, really, really amazing. Just really amazing songwriting that really speaks to issues and really puts what I think is a very important voice from her perspective as a young woman in this particular moment in time out there in a way that people need to hear. Also, stuff that some friends of mine in the hip hop realm have been doing too. Like Jean Grae, who I also was lucky enough to have do some backup vocals on my last record. Her partner Quelle Chris did a record last year that was amazing. Also a Sad13 adjacent project, because the drummer Zoe, also plays with a hip hop artist Sammus, and she’s incredible as well.

PHAWKER: Last year you went public with your own, for lack of a better term, #metoo story from your childhood, we don’t need to dredge all of that up again but the question I wanted to ask is: did revealing that dark secret exorcise the shame and anguish you have been carrying around all these years? Was speaking the unspeakable somehow liberating, like a great weight and been lifted off your shoulders when you unloaded all that baggage you had been carrying around all these years?

TED LEO: Yeah, it was. And I’ll tell you something specific, because I haven’t really been asked about this that much. It seems like it’s sort of a third rail that people don’t really want to touch when I’m doing press, and I understand that. But you know, I would never equate a childhood molestation, you know pedophilia is not the same as sexual assault among teenagers and adults. But I’ll tell you, as much as I’ve thought about this – you know, I’m about to turn 48, and I’ve spent a lot of my life thinking about all of these things – and as much as I’ve thought about this, it was only in the context of this larger conversation that’s going on right now about sexual assault, that I actually started to question myself, in terms of, on the question of – which gets asked of women a lot in situations of assault – “Why didn’t you just leave? Why didn’t you fight back? Etc.” I was a ten year old kid. I was small, but I had agency. It  wasn’t like I was a really small child or an infant or something. When the worst thing that happened to me happened, I was ten. I supposed I could’ve kicked and scratched and ran away. And the fact of the matter is that I had to confront that myself. Not that I was actually asking that question of women, but I never deeply understood until I really confronted this question in myself that I don’t know why. And guess what? It’s not my fucking fault, so fuck you [laughing]. Like I don’t know why I didn’t run away, I have no idea. Shock? Fear of something worse happening? Who knows? There are a million reasons. But I think it really pushed to the forefront just how, just how offensive that is to ask of someone who has been on the receiving end of any abuse or unwanted attention. It’s something that I’m shocked, and I’ve always been shocked, when I hear people still asking that question in 2018. But I don’t think until I went through this most recent process of thinking about my own experience that I deeply understood just how fucked up that question actually is.

wasn’t like I was a really small child or an infant or something. When the worst thing that happened to me happened, I was ten. I supposed I could’ve kicked and scratched and ran away. And the fact of the matter is that I had to confront that myself. Not that I was actually asking that question of women, but I never deeply understood until I really confronted this question in myself that I don’t know why. And guess what? It’s not my fucking fault, so fuck you [laughing]. Like I don’t know why I didn’t run away, I have no idea. Shock? Fear of something worse happening? Who knows? There are a million reasons. But I think it really pushed to the forefront just how, just how offensive that is to ask of someone who has been on the receiving end of any abuse or unwanted attention. It’s something that I’m shocked, and I’ve always been shocked, when I hear people still asking that question in 2018. But I don’t think until I went through this most recent process of thinking about my own experience that I deeply understood just how fucked up that question actually is.

PHAWKER: So moving on from that, if you don’t mind talking about this as well, could you explain what EMDR theory is and how it works? I only ask since it might be helpful to people who don’t know about and might want to consider that as a treatment for their own traumas.

TED LEO: Sure. It stands for Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing. It’s basically a method – I mean it’s not hypnosis – but it’s a sort of therapy where your eyes follow repeated lights or your ears follow repeated sounds or your hands hold something like a buzzer that repeats in motion. Your therapist will guide you through a series of emotions. This was developed as a way of treating PTSD, and it’s often used in the cases of people who are returning from active military service who have PTSD. I don’t know the actual scientific mechanisms of it, but I think what it’s meant to do is to decouple emotions from certain memories. So you can more productively comb through these neural pathways that have been set, and realign them, or actually decouple them. It helps in terms of not having these triggering experiences where we don’t understand why they’re happening to us. It helps in terms of being able to go further with what one would hope would be a healing process.

PHAWKER: Right. So I’ve got one last question on the psych front, and I’m pretty interested to hear what your answer is for this, because I’m still in college, and I know a lot of people who suffer from this or talk about it a lot, and that’s imposter syndrome.

TED LEO: Oh yeah.

PHAWKER: So do you think you could kind of explain that in your own words and talk about how it applies to you, or used to apply to you?

TED LEO: Yeah. That’s another one of those things that I think I really had the language for until pretty recently, and I didn’t always experience it. I think that’s the thing about imposter syndrome that’s important to remember. It can jump in on you at times when other people might not assume you would experience it. I’ve been working in my own world for a really long time, and I’ve played on giant stages and small stages. I developed a confidence to go out there and do what I do, hopefully with humility, but also without fear of being judged. There’s a difference between people not liking what you do and people thinking you’re not worthy of what you’re doing. But it was actually during the process of making this record with Aimee Mann and being surrounded by people who spoke a musical language that I just didn’t have. I wound up overreacting emotionally and receding, and sort of having to tamp that internally, and wound up being in this self-sabotaging ball sometimes, because I – what I realize now in retrospect – was feeling this utter inadequacy and rightfully diminished. It’s tough to remind yourself sometimes that you absolutely have earned your place in the world, and again, it doesn’t mean that you walk into every situation with the confidence that you’re the best person in the room – those people are assholes [laughing]. But you do deserve a place at the table, especially if you’ve been invited to the table. You deserve a place there, and you have to value your own gifts and your own talents and your own perspectives. It’s hard to do sometimes, but sometimes it’s really just a matter of identifying it, and once you’ve identified it yourself, then you can work on it in situations hopefully, and bring your best to the table.

PHAWKER: Yeah, I definitely think it stems from anxiety too, because like I said, I see it all the time here at school, and I can’t tell you how many conversations I’ve had with friends or them having them with me where it’s like you gotta build each other up because you just feel a self-consciousness and you can’t explain why.

TED LEO: Yeah, absolutely. And going back to an earlier question, it’s useful also to think of the constructs in which we are all approaching what we do. I imagine being a young woman in this  world that there are a whole host of challenges that I will never face being a white man. I would speak also to people in my position, or who have the opportunity to help people, as you said, build each other up. You just want to be on the lookout for your friends and your colleagues if they’re experiencing something like this. It’s not easy for them to come out of that shell on their own, and it would be helpful if we could all make that space for each other to be able to – wow, this sounds really cheesy – but to be our best selves.

world that there are a whole host of challenges that I will never face being a white man. I would speak also to people in my position, or who have the opportunity to help people, as you said, build each other up. You just want to be on the lookout for your friends and your colleagues if they’re experiencing something like this. It’s not easy for them to come out of that shell on their own, and it would be helpful if we could all make that space for each other to be able to – wow, this sounds really cheesy – but to be our best selves.

PHAWKER: I agree. Alright, so now we’re gonna move on from all of that weighty psych stuff. I always think it’s interesting when bands go on anniversary tours, so I wanted to ask you about what brought you to the decision to go on a 15th anniversary tour for Hearts of Oak. I know there have been some tough times for you personally, and for the world at large since its initial release in 2003, so how did that inform your decision to go through with it?

TED LEO: Well, yeah it’s been weird. I’ve never really retired from music, so it feels especially weird to look at something as an anniversary when there are songs from the Hearts of Oak record that I’ve never stopped playing since it came out. I mean there are some that I did stop playing, but that’s just the function of continuing to write songs and that there’s only so much time in an average set that you can’t play everything. But it was honestly a suggestion by my booking agent, who noticed that it had been 15 years – like I don’t even notice these things. So I was like, “Oh yeah, that’s interesting.” So he put together a plan for it, and I started thinking about it. He put together this two-night plan where it would be like, one night we play the album, the other night we play more of a normal set. Honestly it just seemed like a fun thing to do. We didn’t make a huge deal out of the anniversary, we didn’t make any special merch. One night, we just played the whole album. I think it was like a little bit of a roll of the dice as to whether or not it was going to be particularly fun, but I really love my band right now – and of course I’m saying this as I’m about to embark on some solo shows, which prompted this interview – but I really do love my band right now. But I think it was the initial getting together to practice the album stuff that we hadn’t played, where everybody was like [laughing] “Oh yeah! These are good songs, these are fun songs!” And I think the longer you go on and the more songs you have, the more you have to shed. And it was fun just for us to revisit them, and remember a couple that we maybe wanted to bring back out as part of a normal set. It just seemed like a good thing to do, and I’ll say this too – it was really, really gratifying to see the way that the audience responded to the Hearts of Oak album night. Like I wasn’t really sure, I mean I don’t know [laughing] – I don’t know, like that album went its cycle and then we kept putting out other albums. But I think it relates to the other part of your question, which is how so many of the political and racial issue songs that were written around that album not only still remain relevant, but are all of a sudden like, especially relevant again. It felt like a little bit more of an event than I expected it to, and it was good to see audience’s reactions to that.

PHAWKER: Would you say that making new music again and going on tour again works as a coping mechanism for this age of Trump? Or if not, what coping mechanisms are you leaning on?

TED LEO: Well, yes and no. I’ll be honest with you, there are times when it feels like it’s the last thing you want to do. There are times when it feels like this is just dumb, and that there are so many more important things. But then I have to go back to the music fan in me, for whom music in trying times has been so important. And then I’m reminded that, oh no, it’s actually one of the most important things. When you get out there and are actually able to talk to people, you know we try to have local organizations that are politically or socially active in their communities – we try to give them a table where they can get phone numbers and emails, etc. It feels good to connect with other humans who also feel similarly and who also need those kinds of things.

PHAWKER: I’m extremely fascinated by the rock of the early aughts and the dotcom bubble, and you’re one of those musicians who got your initial rise sort of before or right around the time that the Internet was taking over. And now you’re making music on the other side of that where all of these streaming services are rampant and have taken over. So what was it like to work on both sides of that, and I wonder what you would say about now, and whether it’s easier or harder to become a successful musician today, i.e. someone who can quit their day job?

TED LEO: Well, it’s harder for me. I wouldn’t speak for everybody. As you say, I think probably Hearts of Oak or maybe even the next record, Shake the Sheets in 2004 – those early aughts records of mine were where I felt like the better part of two decades of working under that old punk model, which was the cottage industry of the normal record industry. But the idea was with the spirit of generosity and hard work, you could achieve something. And it did feel like we’d actually done that, and then, within two years, the rug just got completely pulled out. And I’ll be completely honest with you, I’m not one for figuring out how to monetize every little aspect of living online. In fact, I don’t even really like living online that much [laughing]. I’m not a luddite, I love the Internet, I love using it. I’ve actually forged great personal relationships over social media and stuff, but it gets a little overwhelming I imagine, for people like me who didn’t grow up with it as the main mode of interaction. It can feel a little overwhelming. And the fact of the matter is, I won’t get into specific numbers, but it doesn’t take a lot to do the math to figure out, if you look at how many Spotify plays my last album got, and then look at how many it sold, and then calculate, with some best guesses what the overlap of those two audiences are – you know, calculate the deficit that I’m at. But it’s real, it’s real. And I’m not suggesting that people shouldn’t take advantage of this amazing technology that puts the world at your fingertips. I use it myself, it’s fucking great. But we’re operating with these kind of utopian ideas in a world that is still grindingly capitalist. There’s a lot that has to change before this all shakes out in some equitable way. And it’s not only in the music industry. A lot has changed in the broader way our society is structured too. Yeah. Period [laughing].

PHAWKER: Last question. I don’t really like to do this comparison all the time, because sometimes I think that these two bands are so different in their sounds, but I’ve gotta ask: Beatles or  Stones? And best albums for each, please.

Stones? And best albums for each, please.

TED LEO: Beatles or Stones [laughing]. Okay, I mean look, I’m definitely more of a Beatles person. I’ll go one step further, and say that I’m more of a Paul McCartney and George Harrison person. Not to say that I don’t love John Lennon, but when it comes down to it, those are the songwriters I gravitate more to because of their energy and because of their use of melody. I love what the Beatles did in the studio. Something that I feel like maybe doesn’t get talked about as much with them was really how they pushed recording technology forward, and just the ideas of what you could do with a recording studio. It’s just fascinating to me, and I’m in love with all of their music. Now, I’m not anti-Stones. I love the Rolling Stones as well, but I think it probably says something that when you ask me what I think their favorite album is, I would say Sticky Fingers, because it’s still got that rawness and rock and roll purity that the Stones are praised for, but it’s also deeply soulful in a way that…oh boy, as I’m saying this right now I’m also thinking about Their Satanic Majesties Request, which is also really great, but I’m gonna go with Sticky Fingers. Yeah, it’s soulful in a way that speaks to me in a way that lot of their other albums just don’t. As far as Beatles albums go, I don’t know, I mean it’s tough because there’s so many different phases. I was never a huge Sgt. Pepper’s fan to be honest with you, but there’s a new version that came out last year that’s remixed and remastered, and it’s stunning. But from that era, I think I probably listen to the White Album a lot more. There are songs like McCartney’s “Martha My Dear,” that I think are just masterpieces. But, but, if you force me to choose and I can only take one album of theirs with me, it’s the American mono version of Meet the Beatles, their first album.

PHAWKER: Well, it’s Revolver for me by far.

TED LEO: Revolver’s great too. It’s always tough to choose.

TED LEO PERFORMS SOLO @ ARDMORE MUSIC HALL SATURDAY SEPT. 15TH