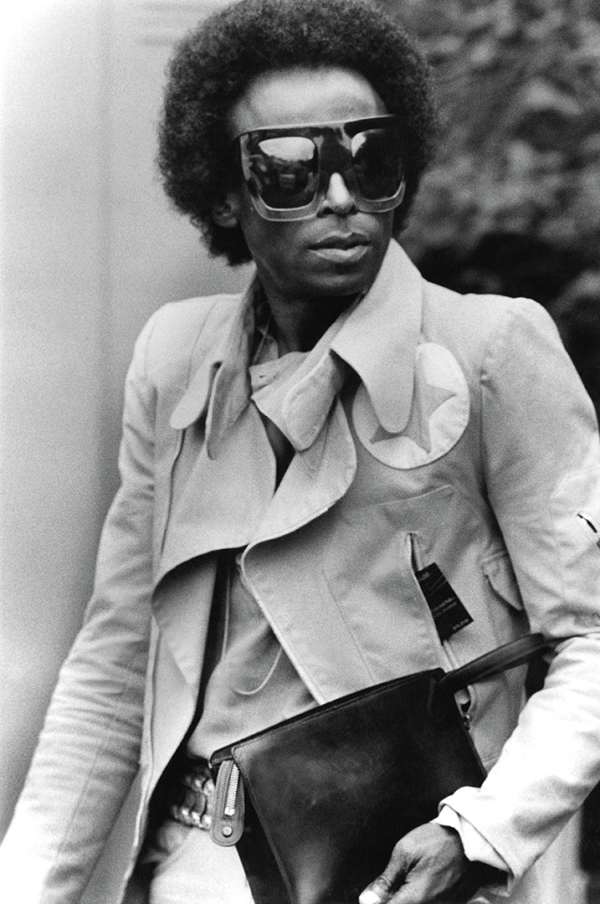

Miles Davis by Veryl Oakland

BY JOSH PELTA-HELLER Jazz In Available Light is a brand-new 328-page photo album of jazz from the 1960s through the 1980s, culled by jazz photojournalist and author Veryl Oakland from his own back pages. In many ways, the book is a sort of antimatter, a physical paradox: here is a current chronicle of a time past, published in print during a decidedly digital age, a daring declaration of the significance of a genre of music whose national popularity has waned to record lows, and — with the announcement from Canon earlier this summer that it would no longer manufacture film cameras — presented in a medium that’s in desperate danger of disappearance.

BY JOSH PELTA-HELLER Jazz In Available Light is a brand-new 328-page photo album of jazz from the 1960s through the 1980s, culled by jazz photojournalist and author Veryl Oakland from his own back pages. In many ways, the book is a sort of antimatter, a physical paradox: here is a current chronicle of a time past, published in print during a decidedly digital age, a daring declaration of the significance of a genre of music whose national popularity has waned to record lows, and — with the announcement from Canon earlier this summer that it would no longer manufacture film cameras — presented in a medium that’s in desperate danger of disappearance.

And if it’s a metaphorical wonder that the book exists at all, it’s a literal one as well: photojournalist Veryl Oakland suffered a catastrophic house flood in 1990 that nearly claimed his entire catalog, soaking  his collection of negatives, and crushing his three-decade-long career in photography under the inexorable weight of damp discouragement.

his collection of negatives, and crushing his three-decade-long career in photography under the inexorable weight of damp discouragement.

It wasn’t until Oakland revisited the films again, some twenty years later, that he realized they were still viable, and was moved to curate and publish this portfolio. The book is a sprawling anthology of images, a handsome and weighty tome featuring an impassioned and self-taught photographer’s life’s work, stylishly adorned with pull-quotes and anecdotes assembled from a career’s worth of his notes, articles, and recollections. It’s a transcendent and timeless document of jazz history, in all of its richest contrasts, in beautifully bound black-and-white glory.

________

PHAWKER: You spoke in the preface to the book about your first experience with jazz being an arbitrary encounter with a Salt Lake City radio station. Is that really the truth, or did you Mother-Goose that at all?

VERYL OAKLAND: No, that’s basically it, that’s what got my juices flowing. Just kind of a chance encounter, basically. It was the theme song of Wes Bowen’s All That Jazz program. It was “Blue Red,” by Red Garland.

PHAWKER: You spoke a little in the book about your own background growing up in South Dakota in the ‘40s and ‘50s, with influences from polka and big-band. With no prior exposure to bebor or hard bop at all, this must have been a radical departure or a sort of culture shock, the first time you heard it. Did you find hard bop and other types of jazz to be immediately accessible to you?

VERYL OAKLAND: It just kind of lit a spark in me. It was just something I hadn’t heard before, yeah. I didn’t grow up around anything like jazz whatsoever, in the Midwest.

PHAWKER: This must have been when, the mid-’50s or so?

VERYL OAKLAND: Yeah. I was born in 1940, so it would’ve been the mid-’50s, I guess.

PHAWKER: Did you sort of follow the evolution of jazz at that point through hard bop and free jazz, and did you found those other genres immediately resonated with you?

VERYL OAKLAND: Not really, no. Actually, what really got my juices flowing was I guess hard bop, because when I heard Red Garland — and then later Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers or Horace Silver — that was strictly hard bop at that time. So it was later that I was able, by doing research on my own, actually discover bebop, by going back to Diz’ [Gillespie], Charlie Parker, Bud Powell and those people.

PHAWKER: You shot with Sun Ra, who’s famous for his development of free jazz. Were you a fan of that music as it was developing then?

VERYL OAKLAND: If you trace him back to his early beginnings, I mean he goes all the way back to swing, and he was one of the stride piano players, in his early days. He really blossomed in a whole different realm of music, throughout his career. I tried to remain open. I guess a best description would be, a lot of people when they talk about Miles Davis, they either loved him when he started out and hated him later on . . . I guess I tried to remain open to everything that was coming down. So while I really did enjoy Miles with his original quintet — and then later with the second great quintet with Wayne Shorter — but I still listened to pretty much everything that the artists were doing, just trying to keep an open mind.

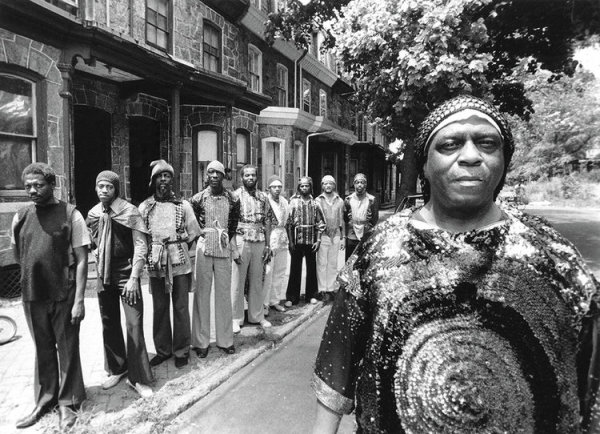

Sun Ra Arkestra by Veryl Oakland

PHAWKER: Sun Ra was eccentric, and you wrote about some of that in your book — were you able to maintain a natural rapport with him? What was shooting with him like, and what do you recall from your interaction with him?

VERYL OAKLAND: Yeah he was very down-to-earth, I found him one of the most affable people I ever spent any time with. As far as his music, he had a way of connecting with everybody, because he didn’t put himself in a box, and he liked to make a whole presentation with his choreography and so forth, you know. As far as the individual, he was very open with me. When we spent time at his home in Germantown, he opened up for over an hour with me, just talking about his background. Really was a huge devotee of Fletcher Henderson, back in the swing era — actually, Fletcher Henderson’s band at the time was better-known and respected than Duke Ellington — and [Sun Ra] spent his early days with Fletcher Henderson, so he never stopped talking about him.

PHAWKER: You mention in the book that you guys shared dinner at a Thai restaurant that he liked?

VERYL OAKLAND: Yeah, in New York, yeah. He really was his own person. Like I mention in the story [in the book], he changed outfits every time for a different photograph, a little bit. It was something I didn’t even notice until later. It wasn’t anything that we talked about, it was just something that he made sure that he did. There was just something about him, he had his own way of operating, onstage and off.

PHAWKER: Philly’s a crucible for a lot of jazz history, actually . . .

VERYL OAKLAND: . . . it’s huge! I mean just in my book alone, I’ve either mentioned or have images of probably at least a dozen people who were impacted or grew up in Philadelphia, just a really rich jazz history in Philadelphia.

PHAWKER: I know you got into photography through your love of jazz, and that you were self-taught. There must have been some artists who seemed sort of larger-than-life to you then, and folks whom you may have wanted to approach for portraits early on. How did you go about doing that, or did you just wait until you had assignments for the journals you were shooting for?

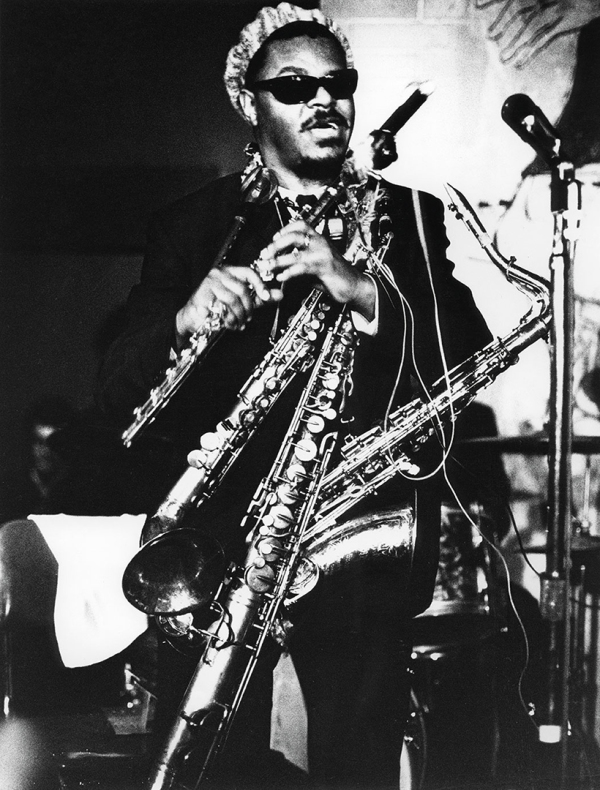

Rahsaan Roland Kirk by Veryl Oakland

VERYL OAKLAND: The one that stands out most vividly in my entire shooting career was Yusef Lateef. As I mention in the story about him, the first time I saw him I was really kind of blown away by the whole act that he had, the whole presentation. So that was somebody that I really wanted to explore, and get some up-close-and-personal photos of, and that’s what I tried to do after I reached out to him, the second time I saw him.

PHAWKER: In terms of the artists of whom you’d been a big fan — I know for example you were a big fan of John Coltrane and you mentioned in the book that you’d just missed getting to shoot with him, because he passed away before you were able to get the assignment. Were there other artists to whom, after that, you resolved to make a point to reach out?

VERYL OAKLAND: Yeah. That was a huge disappointment. You know, a lot of them . . . for example, Jackie McLean, I’d wanted to see and photograph him for a long long time . . . and it was actually just by sticking around awhile, eventually I was able to get most of the people I was really looking to shoot. I can’t think of anyone off the top of my head that I missed during those three decades.

PHAWKER: At what point do you remember feeling comfortable enough with your photography chops that you had the confidence that you’d do justice to the assignments you started to get? Do you ever remember feeling sort of “in over your head,” at any point, being a young self-taught and self-styled freelancer?

VERYL OAKLAND: I think when I started branching out to European and Japanese markets, I pretty much felt that I was ready to accept anything that came along. I was maybe six or seven years into it, early ‘70s. I felt pretty comfortable at that point in accepting just about any [assignment] that came along.

PHAWKER: Your M.O. was to use available light, and to be astutely observant as you note in the book for specific movements that artists made to generate drama on stage. While the live jazz photography was improv on your part, the portraiture was arranged. What was your approach to that, and specifically with respect to making a subject comfortable, or evoking or capturing essential elements of an artist’s personality?

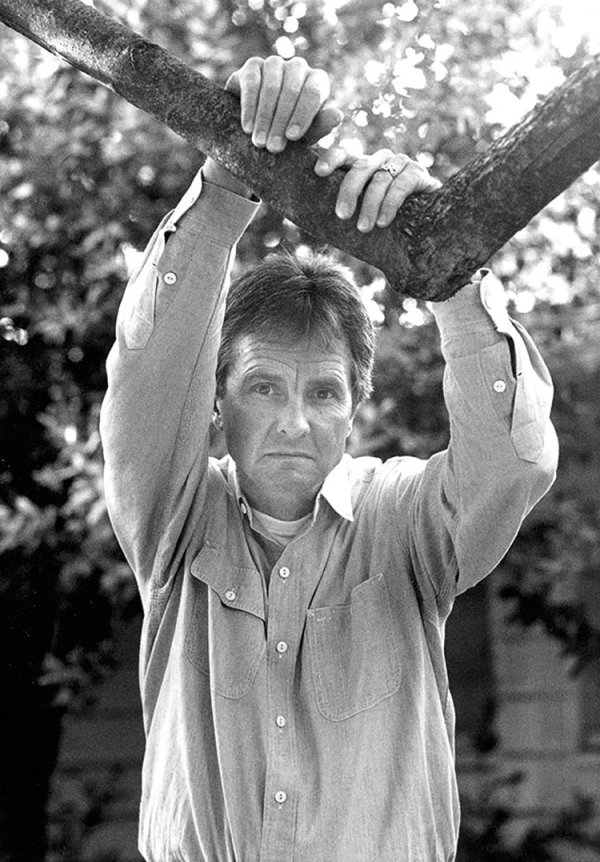

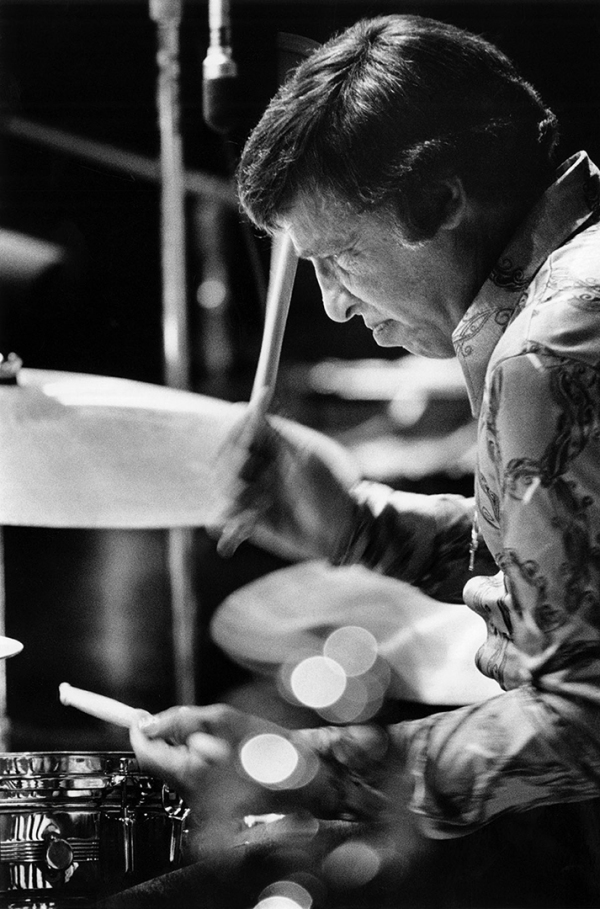

Buddy Rich by Veryl Oakland

VERYL OAKLAND: That’s a good question. I think you kind of tend to develop your own style. I don’t know if you notice but, for example, in a lot of different situations — whether it was confined rooms, or whatever the case might be — I resorted to wide-angle for the up-close-and-personal shots. And maybe photography purists would say “you can’t do that,” but personally I think it kinda adds to what I was able to produce.

PHAWKER: On the occasions when you only have a small amount of time with a subject, did you use any tricks to make them comfortable or “break the ice?”

VERYL OAKLAND: Sure. Yeah some were a little bit more difficult than others, but I don’t know that I had anything other than just a pretty easygoing personality. Let me put it this way: I didn’t wanna force them to do some kind of a pose that was too formal, or made them feel uncomfortable, or whatever the case might be. So maybe with some of the more difficult ones, it took me a few shots before I thought of something that might’ve made them a little bit warmer, or a little bit more loose. But I dunno, I didn’t really think about it. For the most part, many of the people that I spent some extra time with already knew a little bit about me. Or if they knew I was doing something for a particular magazine on assignment, then they were generally more open anyway.

PHAWKER: You mention in the book that you picked up some Nikon gear up front through a buddy in Japan. Did you stick with Nikon throughout your career?

VERYL OAKLAND: Yeah, I did. And in fact, after I began working for [the Japanese jazz publication] Swing Journal, virtually all of the equipment I got from that point forward came from there. So I wound up with I guess six Nikons, and I don’t know how many lenses.

PHAWKER: You started shooting in the ‘60s through about the ‘80s?

VERYL OAKLAND: I stopped shooting in 1990, and that was because of the flood. We had a major flood, and I lost what I considered at the time virtually all of the negatives that I had shot, to that point. And, it was a long period . . . I pretty much gave up, at that point. And then, it was like two decades later when I finally decided I’ve gotta find out really what I still have. And that’s when I painstakingly went through every negative strip, and that’s when I found out many of them had actually survived, and they were still usable. So that was a huge change.

PHAWKER: Were the images in the book printed from those strips?

VERYL OAKLAND: Yeah, there are a few in the book that are not exactly as I originally shot them, they had to be retouched and so forth. I don’t know if you noticed the big wide-angle shot of Shorty Rogers? That negative was pretty badly damaged. So there are a few that aren’t really up to my standards, but I needed to use them based on the stories, and so forth.

Wes Montgomery by Veryl Oakland

PHAWKER: So after the flood, you were essentially demoralized, and stopped shooting?

VERYL OAKLAND: Yeah, basically, I thought that had just taken all the wind out of my sails.

PHAWKER: Was your equipment damaged as well?

VERYL OAKLAND: No, just the negatives.

PHAWKER: Did you ever make the jump to digital, or did you always stick to film?

VERYL OAKLAND: Never did. I don’t even know how to use a digital camera. [laughs]

PHAWKER: And so did you ever pick it back up, do you shoot at all today?

VERYL OAKLAND: No. No, basically when I stopped shooting in 1990, that was pretty much the end of it, right there. Actually the last photograph I took was the self-portrait that you see in the book. That was 1990.

PHAWKER: Do you still listen to jazz?

VERYL OAKLAND: Oh yeah, I follow everything about jazz.

PHAWKER: And so in the last 30 years or so since you’d stopped, you haven’t heard anyone that made you want to get back into the photography aspect again?

VERYL OAKLAND: Y’know, people have asked me that a number of times. Number one, I don’t still have the eyesight. And I don’t really have the drive anymore. I figured that what I shot was the legacy that I’d leave behind. I never really did have any interest to start up again. Part of the reason was that, you know, the loss of twenty years — from the time that I stopped shooting and then decided to put together the book — I would no longer have the continuity, so I felt that it wasn’t proper to start up again.

PHAWKER: As a fellow photographer, sometimes my friends will ask me if feel as though I’m missing out on “experiencing” a one-of-a-kind moment due to being too busy photographing it. Did you ever remember feeling that way, do you sometimes regret not being able to have sort of sat back and just enjoyed these legendary performers without “working” their sets?

Chet Baker by Veryl Oakland

VERYL OAKLAND: Yeah, particularly when you’re doing writing. If your assignment involves doing some actual photojournalism of the entire event, you almost wish that you could kind of duplicate yourself and be in the audience to listen and then still keep your camera gear and keep shooting the whole time. But obviously you have to sacrifice one.

PHAWKER: Did you ever acquire a taste for any other subjects, or had you always stuck with live jazz and jazz portraiture?

VERYL OAKLAND: Nah, that’s really the only interest that I had! Some people might think that’s short-sighted, but actually I devoted my entire photography to just shooting jazz and blues artists.

PHAWKER: Why black-and-white?

VERYL OAKLAND: Basically I liked the medium because it seems more natural, and there are a lot of things that you can do with black and white in the darkroom that you don’t have the luxury of shooting color. And a lot of times, I mean, you see a vibrant color photograph and think that’s really great, and maybe you wouldn’t be able to duplicate that in black-and-white. On the other hand, there are more situations I think — particularly in jazz, and in low-light club situations — that you couldn’t get anywhere near what you can realize through black-and-white.

PHAWKER: It’s been said of Ansel Adams that much of his genius was in the darkroom. I know you did a lot of work printing your own film — did you find this to be a less-appreciated area of photography or place to curate the power of an image?

VERYL OAKLAND: Sure, and a lot of the tricks — not really “tricks,” but solutions that I came up with — were through trial-and-error, as far as, you know, what kind of developer to use. At the time, I was particularly fond of a paper made by Agfa that no longer exists, so it’s difficult to recreate some of the same images that I did before, without that. It was Agfa Brovira, they had a really nice high-contrast paper that allowed me to get some “pop” from the images.

PHAWKER: Given the dramatic changes in the landscape of professional photography over the past fifty years, if you were 25 today and considering photography for a living, would you make the same choices that you did back then toward a career in it, when you were considering it at that age in the ‘60s?

VERYL OAKLAND: That’s a good question. I would think that today it’d be much more difficult to do the same kinda things that I did in the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s. Just access alone I would think would be a really difficult thing, access to the artists and their management. I dunno, not having been associated with the situation that closely lately, I don’t know that that would be the case, but it just seems like it would be very difficult today to have access like I had at that time.

PHAWKER: Did you ever connect with or meet Blue Note photographer Francis Wolff, or any of the other jazz photographers of that era?

VERYL OAKLAND: At different times I met different people. There’s a very well-known Hollywood photographer, Bruce Talamon — most of his career has been spent shooting stills for the major Hollywood movies, but from time to time I’d see him at different jazz festivals and we’d connect. When I was in New York I met people like David Redfern, from London — he did a book awhile back. I never met personally Giuseppe Pino from Milan, Italy, but he was personally one of my favorite jazz photographers, mainly because he took a lot of license to get artists in situations that were really kind of out-of-the-way and unusual, and he was also a very good black-and-white printer.

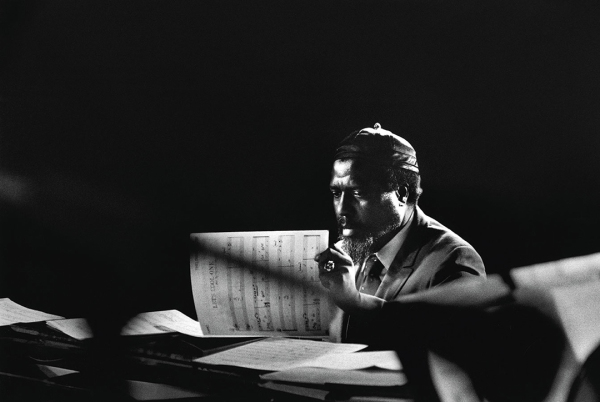

Thelonious Monk by Veryl Oakland

PHAWKER: As you were compiling this book, you culled a lifetime of work, and it must have been difficult to make editorial decisions at time about what to include. Do you feel like there’s stuff on the cutting-room floor that you’d still want to publish?

VERYL OAKLAND: The reason I did that book was because, to my mind there hadn’t been anything done in that same manner. A lot of the jazz photography is mostly just photos and no stories, just maybe even not very much caption information other than ID. So I felt that this was something that needed to be seen.

As far as the stories, I think I got most of those. There’s another half-dozen or more that could’ve been developed. The problem is, the book is already larger than the publisher wanted me to do anyway — he wanted like 288 pages and I finally convinced him to go to 328 — so it was already well beyond what they wanted, what they’re comfortable with. I expect that maybe in a year or two that I may have some kind of a follow-up. I haven’t exactly decided yet how that’s gonna look. It may not be as many stories. But there are a lot of people that I had to leave out that I definitely want to include in some kind of a format. So I’m thinking — right now, I gotta rest a little bit — but maybe in a couple years or so I gotta think seriously about some kind of a follow-up.