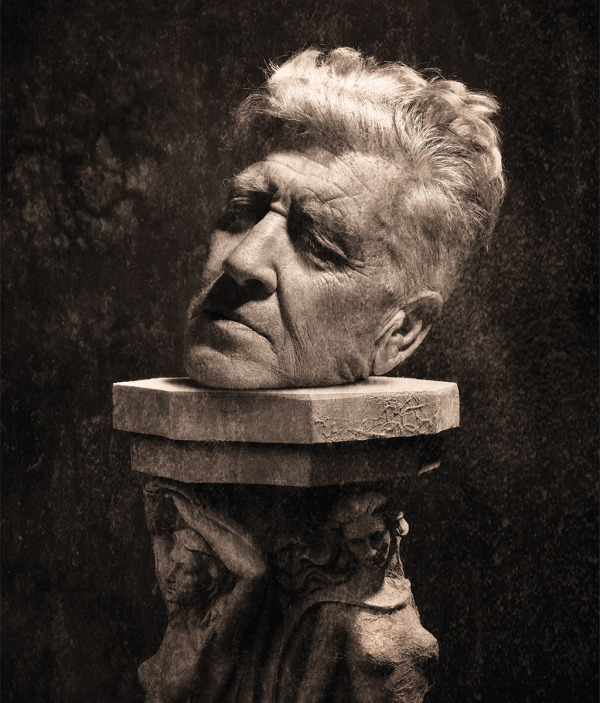

Photo by SANDRO via NEW YORK MAGAZINE

THE GUARDIAN: David Lynch works from a studio on a slope above one of three adjacent homes he owns in the Hollywood Hills, just a stone’s throw from Mulholland Drive. He is reclusive and seldom leaves this little realm, let alone grants audiences to journalists – but he is prepared to now, on the eve of publishing an unconventional memoir-cum-biography, Room To Dream. An assistant escorts me through the house (sleek concrete walls and surfaces, floor-to-ceiling shelves of VHS cassettes and CDs) and up through the garden to the studio. A snake slithered across the path earlier this morning, the assistant says.

Lynch sits in a corner, hunched over a lithograph. The tabletop brims with paint pots, lotions, chemicals, gel formula cement, lithographic paper, pneumatic drills, cables, wires and paintbrushes. There is a mug of coffee, a pack of cigarettes. The director wears cracked, ancient boots, ragged chinos and the remnants of a black buttoned-up shirt that looks to have been shredded by a badger.

It’s a scene that might be intimidating were it not for a great, largely untold secret: David Lynch is a  cheery, congenial soul who rivals the Simpsons character Ned Flanders for howdy-doody niceness. “Hey, bud!” he greets the assistant, offering me a handshake and wide smile. He laughs, often, and yearns for peace on Earth. “I love my life and I’m a happy camper,” he says. “It would be nice if we were all able to fulfil our desires and live good, long, happy lives.”

cheery, congenial soul who rivals the Simpsons character Ned Flanders for howdy-doody niceness. “Hey, bud!” he greets the assistant, offering me a handshake and wide smile. He laughs, often, and yearns for peace on Earth. “I love my life and I’m a happy camper,” he says. “It would be nice if we were all able to fulfil our desires and live good, long, happy lives.”

The studio is a bunker-like structure of concrete and glass that overlooks a panorama of trees, bougainvillea and villa rooftops. You can feel the morning sun and hear birdsong. “I like it up here, the trees,” Lynch says, speaking with the halting lilt of Gordon Cole, the FBI agent he plays in Twin Peaks (only without the deafness). “It’s a feeling I get in LA, a feeling of freedom. The light, and the way the buildings are not so tall. You can do what you want.” Would he like a coffee, his assistant asks? “Yeah, I’m about ready for a hot one, thank you.” There is no toilet up here, so to save trekking down to the house the boss pees into a sink built into the wall. “See that thing with the handle? It pulls out,” Lynch explains. “You can pee right in there. Then you run the faucet.” MORE

WASHINGTON POST: Mystery is important to David Lynch, explanation anathema. His films defy straightforward interpretation; he’s never offered any. About his own biography, he’s long been coy. His press kits used to read simply, “Born Missoula, Montana. Eagle Scout.” So “Room to Dream,” a memoir pushing 600 pages, may come as a surprise. Is the game up?

Fans who share Lynch’s pleasure in mystery will approach this book anxiously, hoping that his secrets may somehow be both revealed and sustained. Luckily for them, he seems constitutionally incapable of self-revelation. In telling his life story, Lynch demonstrates the same disregard for causality and tonal consistency that marks his films. “Room to Dream” is very much the Gospel According to David.

Lynch’s position in Hollywood is itself mysterious. How has such an idiosyncratic, uncommercial director achieved such success? “Room to Dream” provides only partial answers. Luck certainly played a part. A chance meeting with Mel Brooks led to “The Elephant Man” (1980), Lynch’s first mainstream success. A contractual  provision allowed “Blue Velvet” to proceed despite the failure of sci-fi epic “Dune” (1984). “Twin Peaks” arrived in 1990, just when TV audiences were ready for something wild. But all these works required specific conditions to produce them, too, and Lynch and co-author Kristine McKenna use their book to make a case for artists being given the freedom — imaginative and economic — to do that dream-work unrestricted. MORE

provision allowed “Blue Velvet” to proceed despite the failure of sci-fi epic “Dune” (1984). “Twin Peaks” arrived in 1990, just when TV audiences were ready for something wild. But all these works required specific conditions to produce them, too, and Lynch and co-author Kristine McKenna use their book to make a case for artists being given the freedom — imaginative and economic — to do that dream-work unrestricted. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: Dennis was originally supposed to sing “In Dreams,” and the way it got switched to Dean Stockwell was fantastic. Dean and Dennis go way back and were friends, and Dean was going to help Dennis work on the song and they were rehearsing. Here’s Dean and here’s Dennis, and we put the music on, and Dean is in perfect lip sync. Dennis is going along fine at the beginning, but his brain was so fried from drugs he couldn’t remember the lyrics. But I saw the way Dennis was looking at Dean and I thought, this is so perfect and it switched around. There’s so much luck involved with this business. Why did it happen like that? You could think about it for a million years and not know it was the way to go until you saw it right in front of you. MORE

So we know now that Dean’s going to sing. Frank says, “Candy-colored clown” and puts in the cassette and Dean picks up the light. Patty Norris [the production designer] didn’t put that light there. I didn’t put that light there. Nobody knows where it came from, but Dean thought it was for him. It was a work light, and nothing could be better than that being the microphone. Nothing. I love it. We found a dead snake in the street around the time we shot that scene and Brad Dourif got hold of it, and while Dean was doing “In Dreams,” Brad was standing on the couch in the background working this thing and it was totally fine with me.

VULTURE: Last Friday, Lula, she’s 5 and a half, got an introductory TM lecture. On Saturday, she got taught. Sunday, she got a follow-up talk and what they call her “word of wisdom” — her walking mantra. All my kidsLynch is father to two daughters, the middle-aged Jennifer and school-aged Lula, and two adult sons, Austin and Riley. started when they were 6 or 5. I’ll tell you a story: I was in Italy, and this nun was asking me about Transcendental Meditation for children and wanted to know at what age kids were old enough to start. I said, “When they’re old enough to keep a secret.” She said, “Oh, no! No secrets!” But you get your mantra and you’re not supposed to say it out loud because it’s meant to take you inward not outward. The nun freaked out about that. Maybe that tells you something about nuns.[…]

See, I’m not — I’m not the greatest parent. I love all my children and we get along great, but in the early years, before you can have a relationship of talking to them, it’s tough. And I would get divorced and stuff — I’ve got four kids and three divorces. The work is the main thing, and I know I’ve caused suffering because of that. But at the same time I have huge love for the kids. It’s a tricky business, because nowadays — when I was growing up, for instance, I was on a Little League baseball team and my parents  [Lynch’s father Donald was a research scientist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and his mother, Edwina, was an English language tutor. The Lynch family, which also included David’s sister Martha and brother John, moved around a fair bit, spending time in Idaho, Washington, and Virginia.] never came to the games. I wouldn’t want ’em to come to the games. I didn’t want my parents to go to my high-school graduation. I wanted them to stay away.[…]

[Lynch’s father Donald was a research scientist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture and his mother, Edwina, was an English language tutor. The Lynch family, which also included David’s sister Martha and brother John, moved around a fair bit, spending time in Idaho, Washington, and Virginia.] never came to the games. I wouldn’t want ’em to come to the games. I didn’t want my parents to go to my high-school graduation. I wanted them to stay away.[…]

Nowadays parents are involved with every single thing and there’s stay-at-home dads. It seems strange but that’s how things have changed. Emily, my wife, sends me pictures if she’s at the park and sees a dad there. She’ll say, “Look, a dad is here” and I’ll say, “That’s a homeless man.” But I shouldn’t make fun. It’s beautiful for that man’s kid that he’s there. Everybody’s got their own way. MORE

EDITOR’S NOTE: On September 10th, 2014, David Lynch gave a press conference at The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts to promote DAVID LYNCH: The Unified Field, the first major retrospective of his paintings in an American art museum. The retrospective is something of a homecoming for Lynch who studied painting at PAFA from 1966-1967, back when the City of Brotherly Love was a desolate hellscape of decay and despair after years of white flight, industrial collapse and seething racial animus. From 1965-1970, Lynch lived in a section of the city that has come to be known as The Eraserhood. It was in Philadelphia that Lynch first transitioned from painting into filmmaking. In 1970, he headed to Los Angeles to begin work on Eraserhead. At the press conference, Lynch talked about how he drew inspiration from the horrors he witnessed during his days in Philadelphia, and expressed his sadness that the city is no longer a soot-stained miasma of fear and loathing and ultra-violence, that his malevolent Rosebud has been rendered harmless and ordinary by gentrification. The short film you are about to watch is a compendium of Lynch’s remarks about filmmaking, painting, smoking, and the nature of art. Filmed and edited in high Lynch-ian style, this short film incorporates David Lynch’s music, paintings, and films along with his charm, wit and insight into the creative process. A must-see for fans of his work.