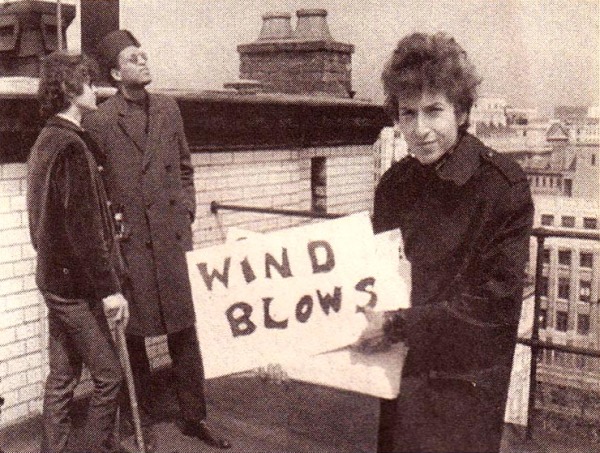

From left to right, Bob Neurwith, Tom Wilson, Bob Dylan by D.A. Pennybreaker’s “Don’t Look Back”

TEXAS MONTHLY: Without this producer, Bob Dylan would not have broken through like he did—effectively bringing on the swinging sixties and changing music forever. Without this producer, Simon and Garfunkel might have quit before they ever got started, the Velvet Underground might have stayed underground, Frank Zappa might have spent his career recording on hapless independent labels, and jazz greats Sun Ra and Cecil Taylor would definitely have labored longer in obscurity than they already did. This producer helped them all find their voices and realize their visions, revolutionizing American music. He was a Harvard graduate. He was a Republican. He was a black guy from Waco, Texas. […]

At first Wilson wasn’t thrilled with the prospect of working with someone like Dylan. “I didn’t even particularly like folk music,” he later told Melody Maker. “I’d been recording Sun Ra and John Coltrane, and I thought folk music was for the dumb guys. This guy played like the dumb guys. But then these words came out.” He told Albert Grossman, Dylan’s manager, that they should put a band behind him—“you might have a white Ray Charles”—but Dylan was comfortable doing things solo.

The scruffy 20-year-old clicked with the well-dressed 30-year-old, and they developed a good working relationship, doing two more acoustic albums (The Times They Are a-Changin’ and Another Side of Bob Dylan) before Wilson helped usher in the modern age in 1965 with Bringing It All Back Home, Dylan’s half-electric, half-acoustic tour de force. The year before, Wilson had overdubbed a band onto three of Dylan’s older songs, including “House of the Rising Sun,” but the sound didn’t work. On Bringing It All Back Home, Wilson got it right, bringing in a band of electric guitarists, a couple of bassists (including Bill Lee, director Spike Lee’s father), and a drummer. The result was Dylan’s first modern masterpiece, “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” whose frantic, lurching bluesy vibe would set the tone for the rest of the sixties. You can actually hear Wilson at the beginning of another song on the album, “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream,” in which Dylan makes a false start, stops, starts laughing, and is joined by a laughing Wilson; after a few seconds you can hear Wilson say, “Wait a minute now. Okay, take two.” Then the band kicks in. As a listener, it sounds like you’ve been let in on a secret: Oh, so that’s the way they make records.

It was the beginning of a new Dylan—and a new era. Wilson would always say about Dylan going electric (as he did in a 1976 interview), “It came from me.” When Rolling Stone’s founder Jann Wenner interviewed Dylan in 1969 and asked him about Wilson’s claims to have brought Dylan to rock ’n’ roll, Dylan laughed but added, “He did to a certain extent. That is true. He did. He had a sound in mind.”

Wilson only did one more song with Dylan, and it was his biggest hit ever: “Like a Rolling Stone,” considered the number one rock song of all time by Rolling Stone magazine. Again Wilson recruited the band, and also invited a friend of his, Al Kooper, to watch. At some point, Kooper, a guitar player, slipped behind the organ during recording and began to play a simple line, ultimately giving the song its signature riff. At the start of one of the alternate takes, you can hear Wilson say, “Okay, Bob, we got everybody here, let’s do one.” This sums up Wilson’s production style: bring people together, get them ready, and let it rip. MORE

Tom Wilson interviews Lou Reed, circa “White Light/White Heat”