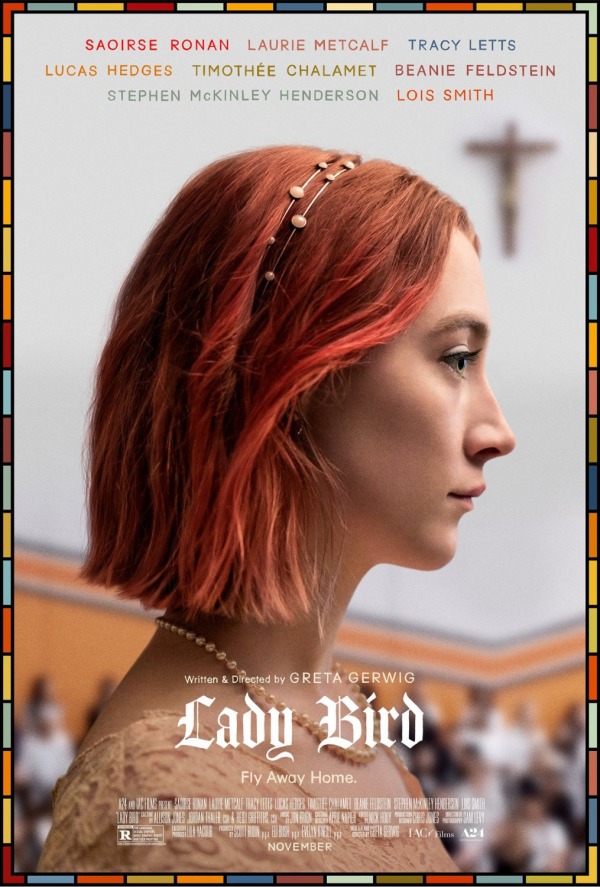

LADYBIRD (Directed by Greta Gerwig, 94 minutes, 2017, USA)

BY CHRISTOPHER MALENEY FILM CRITIC Coming of age stories, or bildungsroman for those who know your literary terms, represent a foundational storytelling archetype of the western world. We love bildungsroman, from Greek myths and fairy tales through Harry Potter and the whole Young Adult canon, for a number of reasons. These stories allow older readers to re-live their formative years and experiences and younger readers to find characters and experiences that instruct them in their own life-choices. Most importantly, though, bildungsroman explore the central question of any society by asking what the requirements are to be an adult, what rituals must be performed to cross from childhood into adulthood.

BY CHRISTOPHER MALENEY FILM CRITIC Coming of age stories, or bildungsroman for those who know your literary terms, represent a foundational storytelling archetype of the western world. We love bildungsroman, from Greek myths and fairy tales through Harry Potter and the whole Young Adult canon, for a number of reasons. These stories allow older readers to re-live their formative years and experiences and younger readers to find characters and experiences that instruct them in their own life-choices. Most importantly, though, bildungsroman explore the central question of any society by asking what the requirements are to be an adult, what rituals must be performed to cross from childhood into adulthood.

Lady Bird, Greta Gerwig’s tour de force directorial debut, is on the surface just a 21st century bildungsroman. Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson (Saoirse Ronan) is a unique, headstrong girl of seventeen years old — when, in the opening scene, her mother belittles her aspirations for an east-coast college, Lady Bird simply opens the car door, unbuckles her seatbelt, and rolls out, consequences be damned. While Lady Bird is unsure of what she wants from her life, she knows that she wants to get out of Sacramento, preferably to New York, Connecticut, or New Hampshire, where “writers go to to be alone in the woods.”

The plot, such as it is, comes through a series of vignettes and snapshots that make up a whole experience, just like real life. Lady Bird joins the theater club, but doesn’t get the lead, and there is no year-ending performance that brings her to adulthood. She loses her virginity to a wannabe anarchist, but when he turns out to be just an asshole she goes to prom with her best friend, Julie (Beanie Feldstein). Family problems come and go throughout the movie, as do questions of wealth, mental health, and satisfaction. Love and friendship, like first drinks or first cigarettes, mingle together in memory, leaving meaning only with the hazy impression that linger on afterwards of good and bad times.

The only definite plot arc to the film is Lady Bird’s attempt to escape to an Eastern college, which is not much of a plot, per se, as few of her choices and actions directly affect the outcome. That this is not problematic speaks to Gerwig’s strength as a storyteller for having chosen a narrative style that emulates what is actually found in reality, where significance is not contained in a moment’s dialogue, or the setting of a scene, but in the whole panoply of decisions and revisions that make up a life. The ending that we are left with is not necessarily a conclusion, though it is satisfying, because Lady Bird’s story is not finished. Only this act of the narrative is closed.

As I left the theater and strolled back into the night, I was left with a satisfying sort of sadness, and a host of questions. Where was Lady Bird now? Did she do well in school, or did she have to transfer out? Did she like where she found herself? Were the massive loans she took on crippling to herself and her family? Is she still paying them off fourteen years later? Or, like Gerwig, did she get plucked from the millions to find success? We cannot know, we can only watch and re-watch this hilarious, heartwarming, occasionally excruciatingly awkward, tale that examines in detail what it means to come of age in 21st Century America.