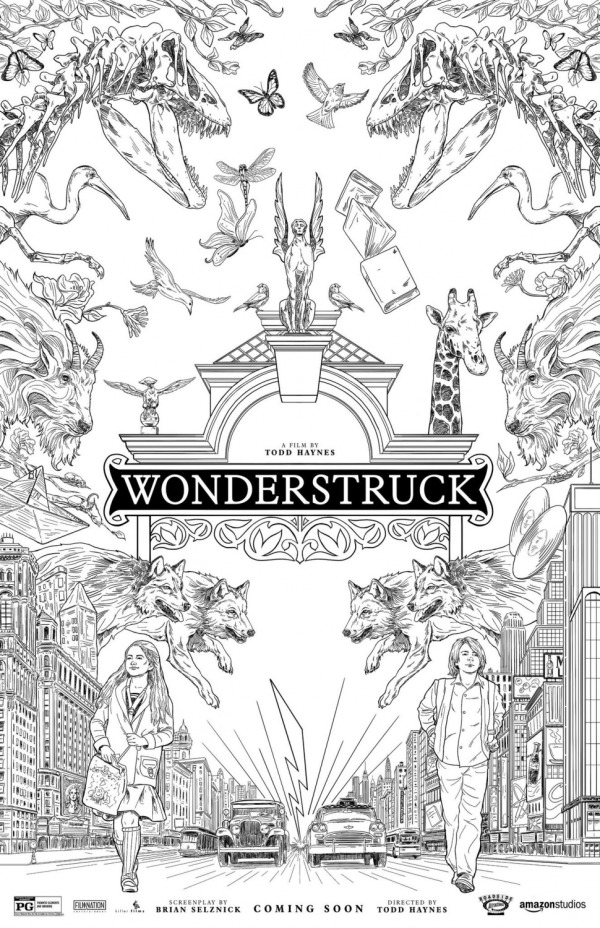

WONDERSTRUCK (Directed by Todd Haynes, 116 minutes, USA, 2017)

BY CHRISTOPHER MALENEY FILM CRITIC Ah, New York City. The Big Apple. The City of Dreams. The ultimate actualization of the American Dream, the place you go when you have a dream of making it — where any kid can grow up to be a star. A home to probably eight hundred languages spread across more than eight million people. A city of strangers minding their own business. A city where you could live a parallel life to someone and never know it. There have been hundreds of movies, books, songs and plays about New York City; some feature it just a backdrop, while others seek to explore the city’s uniqueness, delving into the heart of the narratives of wonder and discovery that make up The Big Apple’s lasting enchantment.

BY CHRISTOPHER MALENEY FILM CRITIC Ah, New York City. The Big Apple. The City of Dreams. The ultimate actualization of the American Dream, the place you go when you have a dream of making it — where any kid can grow up to be a star. A home to probably eight hundred languages spread across more than eight million people. A city of strangers minding their own business. A city where you could live a parallel life to someone and never know it. There have been hundreds of movies, books, songs and plays about New York City; some feature it just a backdrop, while others seek to explore the city’s uniqueness, delving into the heart of the narratives of wonder and discovery that make up The Big Apple’s lasting enchantment.

Todd Haynes’ Wonderstruck wants to be one of the latter kind of movies. It wants to show how two lives, separated by fifty years, can run in the same way. To wit: In 1927, Rose, a deaf-mute girl, escapes her stifling life in Hoboken to find a stage actress she is curiously obsessed with. In 1977, Ben, an eleven year old boy made deaf by a lightning strike, travels to New York City to find out who his father is, and why his late mother could never explain his parentage. Throughout the film their lives intersect in ways that are supposed to reveal something about imagination and the creativity of youth. Instead, it mainly advertises the joy of curating a museum, and the difficulty of suffering a sensory disability in an unhelpful world.

There is an old adage in show business, “Never work with kids or animals.” While sometimes there are notable exceptions to this rule, it exists for a reason. Animals are hard to train, and it’s not always easy to get a good performance from a child. Certainly that’s the case here, as Ben (Oakes Fegley), really isn’t that likeable. I want to sympathize with him; he’s got a lot on his plate for a small kid in a big world, but he doesn’t do anything to earn my sympathy. When, in an early flashback, his mother gives him a birthday present he is bitter and ungrateful. Towards the end of the movie, Ben’s only friend, Jamie (Jaden Mitchell), reveals a key piece of information he had kept concealed; Ben’s infuriated reaction is necessary for the plot, but stole the last of my sympathy.

Our other hero, Rose (Millicent Simmonds), is a much more likable and engaging protagonist. Her narrative is entirely silent, like the movies of the era, but her emotional journey is conveyed very well through facial expressions and physical gestures, like tearing up the overly dense tome her tutor has assigned or peering curiously at the displays in the Museum of Natural History. Sadly, her plot takes a backseat to the more expository narrative of Ben’s search.

In writing there is a rule to “show don’t’ tell” a story. It means that the reader should be brought into a story by physical and emotional details that create the story in their mind. To extend it to films, an audience should engage in a story on a level with their characters, taking part in it with them. Unfortunately, Wonderstruck totally breaks this rule in its culminating act. The meeting of the two separate narratives occurs by an epistolary narration that might have been smooth in the source material, but here feels not just jarring but boring. As Rose explains to Ben the details of his parentage, all mystery is quashed by a visually interesting but narratively dis-engaging revelation. I stuck it out until the end hoping that I would at least find a satisfying conclusion to her story. Sadly, it was not to be.