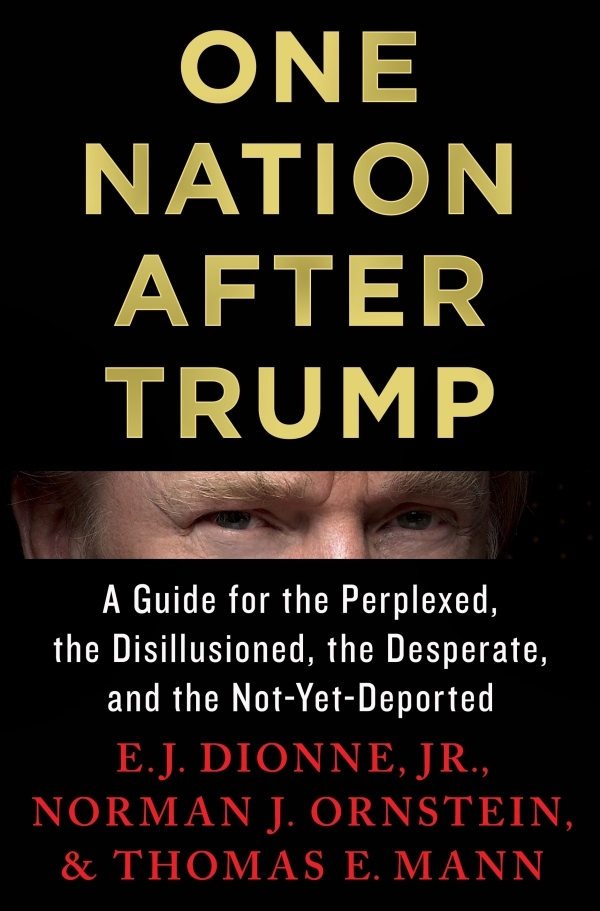

BY JONATHAN VALANIA These are dark days for American democracy. The combination of gerrymandering, dark money, fake news, voter suppression, foreign interference and a deeply divided electorate have had a profoundly corrosive effect on the credibility of America’s claim to be governed by majority rule — that the outcomes of our elections accurately reflect the will of the people. The result is a president with a 67% disapproval rating after just 10 months in office, according to a recent Associated Press poll, and a Congress that has repeatedly tried to ram through a repeal of the Affordable Care Act with a replacement plan that has an approval rating south of 19%. How we got to this point and how we get back to where we once belonged is the gist of the new book One Nation After Trump: A Guide For The Perplexed, The Disillusioned, The Desperate And the Not-Yet Deported written by three of the most credible and astute political thinkers of our time: E.J Dionne Jr., a Washington Post columnist, Georgetown professor and Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution; Norman J. Ornstein, Resident Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and a contributing editor/columnist for the National Journal and The Atlantic; and Thomas E. Mann, resident scholar at the Institute of Governmental Studies at UC Berkeley as well as Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institute. Both Dionne and Ornstein will be discussing their book at the Philadelphia Free Library tomorrow night. Recently we got both men on the horn to discuss the following: Voter suppression, undoing gerrymandering, the resulting minority rule, disbanding the Electoral College, Trump’s serial violations of the basic norms and institutions of American democracy and their proposals to harness the pervasive outrage and disillusionment of the electorate in the wake of the 2016 election and remedy all of the above with a Charter for Working Families, a G.I. Bill for American Workers and the Contract for American Social Responsibility.

PHAWKER: What did voter suppression look like in 2016? Where did it come from? How do we overcome it?

EJ DIONNE: Well all of these voter ID laws that seem neutral on their face aren’t. And  some of them are laughably not neutral. In Texas they passed a voter ID law where you could not use a government issued state university or college ID, but you could use a concealed carry permit. Well that tells you who they are trying to help vote and who not. But even just a driver’s license. A lot of people in the inner city don’t have cars, they don’t need a drivers licenses. People in the suburbs get them as a matter, of course, because they can’t live their lives without driver’s licenses. That simply cuts out of the electorate a lot of people in the inner city. That’s clearly not neutral. So this is clearly an effort to suppress the votes of certain kinds of who tend to vote Democratic. They are disproportionately minority, they are disproportionately poor, and in many cases they are young. Probably, and I think we need to do more work on this, but the place you seen this most is in the fall off in African American voting in Milwaukee. There was certainly going to be some fall off in the African American vote with Barack Obama not on the ballot but there is at least some evidence, and I think we need to sort of nail this down, that the tough voter ID laws in Wisconsin may have suppressed a significant number of votes, and that state was very close in the election.

some of them are laughably not neutral. In Texas they passed a voter ID law where you could not use a government issued state university or college ID, but you could use a concealed carry permit. Well that tells you who they are trying to help vote and who not. But even just a driver’s license. A lot of people in the inner city don’t have cars, they don’t need a drivers licenses. People in the suburbs get them as a matter, of course, because they can’t live their lives without driver’s licenses. That simply cuts out of the electorate a lot of people in the inner city. That’s clearly not neutral. So this is clearly an effort to suppress the votes of certain kinds of who tend to vote Democratic. They are disproportionately minority, they are disproportionately poor, and in many cases they are young. Probably, and I think we need to do more work on this, but the place you seen this most is in the fall off in African American voting in Milwaukee. There was certainly going to be some fall off in the African American vote with Barack Obama not on the ballot but there is at least some evidence, and I think we need to sort of nail this down, that the tough voter ID laws in Wisconsin may have suppressed a significant number of votes, and that state was very close in the election.

PHAWKER: To address this, would some sort of comprehensive federal law address these matters?

EJ DIONNE: Well, we have one it was the Voting Rights Act, and the Supreme Court gutted the Voting Rights Act. And what we need to do is reinstate the Voting Rights Act. Rewrite it to make it very difficult for the Court to knock it down. Because when we had the Voting Rights Act in place, the federal government was challenging these laws and winning in court to knock these laws out. There were some court decisions on these voter ID laws where it was blatantly obvious that they were tailored to knock out certain kinds of voters. But we don’t need anything revolutionary; we just need the good old voting rights act that the Supreme Court gutted.

PHAWKER: In the book you talk about the rise of minority rule, or non-majoritarianism, as you guys coined it. Explain that for readers who may not know what that means necessarily, and how we get there, and what are the dangers of this?

NORM ORNSTEIN: We had a system that was set up not as a pure or direct democracy, and it was one that created an Electoral College that was not only suppose to provide some protection and role for every state, but also, of course at the time, the popular votes were not of a significance at all, it was suppose to be a group of reasonable elites, leaders, who would examine the candidates and make sure we  ended up with a president that wasn’t a demagogue or unprincipled person, this is something that Alexander Hamilton of course wrote about very eloquently, given his fears of Aaron Burr. We also had this balance, a House of Representatives that was suppose to represent the people and really be responsive to popular views and popular demands.

ended up with a president that wasn’t a demagogue or unprincipled person, this is something that Alexander Hamilton of course wrote about very eloquently, given his fears of Aaron Burr. We also had this balance, a House of Representatives that was suppose to represent the people and really be responsive to popular views and popular demands.

In fact, there was a lot of discussion at the time of even possibly having election every year instead of every two years. And every Senate where every state would play a role. At the time the ratio of population between the largest and smallest states was 13-1, now it’s 70-1. And, not only do we have that, when we look to the future, we know that the population projections are such that by 2050, 70% of Americans will live in just 15 states. So, just to start with the Senate, what that means is 70% of Americans will have 30% of the representation in the Senate. And that’s an enormous distortion that does a couple of things that are very troubling: one is, that when we have a population that is increasingly moving into metropolitan areas where the economic vibrancy and growth is, their ability to influence policy will be very much diminished which will have an impact on our growth and our policies, not to mention being very anti-democratic even in the context of a small-R republican form of democracy; and the second is that more and more power is going to be going to smaller states with dwindling populations and very homogeneous ones that don’t represent the diversity in America, and ones that are much more white in their populations and that also means we are going to have less and less responsiveness to what is occurring in our country.

Now, the Electoral College has already been distorted beyond recognition while we have individuals who are electors, the role that they play is basically to sit down and, except for the very occasional “safe” one, just cast a vote based on how the state has voted—or, in a couple instances, maybe in Nebraska, how the congressional districts have voted as well. So, we don’t have this system of deliberation in an Electoral College that we use to have. But for the same reasons the Senate has become distorted, the Electoral College has become distorted. And so if you look at the entire course of American history, from the time when the popular vote was actually counted in any significant way and meant to mean anything, 1824, all the way up to 1996, we had arguably three elections where the candidate who won the popular vote did not become president. Two of those were kind of weird, they were starting with 1824 where you had four candidates for president who split elector votes and then the top three were voted on in the House of Representatives, but really only one election where it was pretty clear that by a narrow margin the winner of the popular vote  lost the presidency, in the five elections since we’ve had two of those. So we’ve moved from something that was extremely rare to something that has happened 40% of the time. And we know, given how elector votes are distributed, giving many more votes to smaller states, none of which no matter how tiny get three electoral votes, and the gap in power between a Wyoming and a California continues to grow, we’re going to have more elections where the winner of the popular vote is going to lose the presidency.

lost the presidency, in the five elections since we’ve had two of those. So we’ve moved from something that was extremely rare to something that has happened 40% of the time. And we know, given how elector votes are distributed, giving many more votes to smaller states, none of which no matter how tiny get three electoral votes, and the gap in power between a Wyoming and a California continues to grow, we’re going to have more elections where the winner of the popular vote is going to lose the presidency.

Now, those are the rules, but what we can say is that the larger attitude that prevailed in the year 2000, when George W Bush lost the popular vote by a half a million, but still by the controversy in Florida he became the president. The public reaction was like, ‘Well those are the rules, in tennis it doesn’t matter how many games you win, it’s the sets,’ and by the second time people are beginning to question the legitimacy of the outcome, and this time it was almost three million votes separating them, and by the third time we’re going to have more and more people who are going to question the outcome—it’s a real danger to the legitimacy of the system. And then in the House of Representatives, where we know a combination of gerrymandering and the nature of residential patterns has created a sort of bias, the gerrymandering alone for the decade we’re in, giving republicans by a number of the better estimates, somewhere between 16 or 17 additional seats, that we’re in a period where one party—the Democratic party—may need to win 60% or more of the popular vote to get barely 50% of the seats. And we know that the districts have become so homogeneous that national trends do not matter in the slightest. I’m going to a session this week by an organization called Fair Vote, suggesting that probably 380 – 390 of the House seats are entirely predictable 18 months in advance of the election because they are safe for one party or the other. The last time they did this long before the last election they were accurate in every single one of the predictions of the 380-plus seats that are in this category. That means that we are not operating the way the framers expected and are increasingly distorting the process.

PHAWKER: If we decided we wanted to do away with the Electoral College, what would the process be?

NORM ORNSTEIN: There are two ways to do this: one you would need a constitutional amendment, and that of course is simply not going to happen. Practically speaking will never happen in part because you need a lot of states that would ratify the reduction of their own power. And the second way which is being promoted now by a lot of individuals and groups, one new one called Making Every Vote Count, is basically an interstate compact. Right now the states that represent the 165 electoral votes, 105 short of the majority required, have an active legislation that say that only when states representing 270 electoral votes have done so, that they will have their state’s electoral votes cast for the party that wins the popular vote. So you can do this voluntarily. States have a substantial amount of leeway to  allocate their electoral votes. This is not something that is going to happen over night, it’ll take some time, but I think we’re going to have more and more Americans across the spectrum understanding that we’re going to have to rethink this process, given what’s happened to the population in America and what the electoral college means now as to what it use to be doing.

allocate their electoral votes. This is not something that is going to happen over night, it’ll take some time, but I think we’re going to have more and more Americans across the spectrum understanding that we’re going to have to rethink this process, given what’s happened to the population in America and what the electoral college means now as to what it use to be doing.

PHAWKER: Assuming the will is there to do this, how is gerrymandering undone?

NORM ORNSTEIN: It technically or theoretically could be done by Congress. If Congress, which has the constitutional authority to regulate the time, manner, and place of the elections, could enact a statute that knew boundary lines, or at least would require a different process for congressional districts—they couldn’t do it for the states—the practical re-eddy is this is going to be done state by state and what we’ve seen is a number of states—now Arizona joining California joining Iowa among them, have opted, usually through referendums in the states, to have intended, non-partisan commissions play a key role in setting up congressional district. And what they’ve done—and Iowa is the best example—they’ve created more competitive districts, they’ve created farer districts, they’ve created heterogeneous districts, and its doable. Now its no panacea, if we ended the practices that have been going on now. The fact is, because of the “Big Sort” as its called, Bill Bishop coined the term, the fact that Americans are increasingly living in places that are surrounded by like-minded people, we still are going to have far too many homogenous districts that become like echo chambers.

PHAWKER: The Big Sort?

NORM ORNSTEIN: Yeah the book Big Sort done about 20 years ago by Bill Bishop, and it’s been updated since. And it’s quite powerful.

PHAWKER: Now you don’t think the Supreme Court would have anything to do with this, or the one to trigger this?

NORM ORNSTEIN: We’re hoping that—I was talking about the political elements of it—of course the court is a political element too—we have this big case coming forward soon to be argued. Years ago in a case called Vieth, a Pennsylvania redistricting case on the issue of partisan gerrymandering, Justice Kennedy in a 5-4 decision that said basically we don’t have a standard to judge whether a redistricting process is too distorted, too partisan, Kennedy said that we don’t have a standard now, and that, down the road, I don’t see why we shouldn’t and I’d be open to that. And what we have now is a very compelling standard in Wisconsin, to put it in simple terms, relies on looking on wasted votes—there are all these wasted votes in a congressional election, and what do I mean by that: if you get 49.9% of the votes and you lose, all those votes are wasted. If you receive 70% of the votes, then 20% are wasted. You only needed 50. And those happen all the time but you can develop a process, it’s been done in Wisconsin—fairly simple—to show when the number of wasted votes is so far out of the norm and what you would expect given variations in elections, that it represents a clear bi-partisan effort packing some congressional districts and giving others just enough to make sure their safe on their side, done in an egregiously partisan way. It a reasonable standard and we’ll see if Justice Kennedy is telling the truth when he said he would accept a standard. That would make a real difference—it would put some boundaries around the redistricting process. I’m not widely hopeful, because we had an instance in Texas where multiple courts including very conservative courts have appealed, and said that this Texas redistricting is outrageously  partisan, and had to go back and draw the lines. And the Supreme Court, with its usual predictable partisan 5-4 vote, took off or put a stay on that and let them go forward with their distorted plan for this coming election. Now we don’t know how much of that is going to carry over but we can’t be sure that the courts are going to do the right thing here.

partisan, and had to go back and draw the lines. And the Supreme Court, with its usual predictable partisan 5-4 vote, took off or put a stay on that and let them go forward with their distorted plan for this coming election. Now we don’t know how much of that is going to carry over but we can’t be sure that the courts are going to do the right thing here.

PHAWKER: Moving on to Trump’s serial violation of the norms of American democracy. I’m not sure just how much it registers with the American public how much of American democracy isn’t written into law, that it is largely an honored tradition. And really, the only thing you need to do to undo an honored tradition is not honor it. So, I guess my question to you is do you think its time that we start codifying some of these “norms” into actual rules or laws.

EJ DIONNE: Well I do think we need to codify some of them. I think all presidential candidates should be willing to make their income tax returns public. There are some disclosure laws, but candidates were doing it because they were expected to do it. Now we know there will be some candidates who refuse to do it, and we should count on them to do that. We should pass a law so that they will have to do that. But you can’t codify everything, and that’s why norms are so valuable. There are certain things you just expect people to do, and if they want to get around the existing laws they will. The other norm that’s obvious that Trump has broken relates to separating himself from his own businesses. For years and years, presidents simply did that as a matter. Of course, there are some conflicts of interest laws, but there is also some limit, because of the separation of powers, on what congress can require. We expected presidents to that, and they did. Jimmy Carter disconnected himself from all of his peanut farming and other presidents have sort of put businesses behind them. And so, again, I think where we can codify norms in ways that will work, we should do that. But we also need a president willing to live by them. We should demand it, and make it an expectation when anyone runs for president. If someone keeps getting away with breaking norms, norms will be broken by a lot of people who don’t want to live up to certain ethical standards.

PHAWKER: You talk about a new era of rebuilding civil society, re-engaging and empowering the American people, renewed patriotism related to a new spirit of empathy. I realize you wrote a whole book explaining how this could work, but if you could briefly explain how we get there, in your estimation.

EJ DIONNE: The things you just mentioned are harder to do than passing specific legislation. But first, on a practical level, that the economic damage done to our communities around the country by deindustrialization, has not only made it harder for a significant number of people to make a living (and by the way that’s true of inner cities, of African Americans and Latinos also as well as the white working class. We have to think of their problems in tandem. We have a line in the book saying ‘holding one groups pain against another groups pain is a recipe for division and inaction.’) But we also think that the damage done by this is to the fabric of these communities the organizations that people built to bring citizens together. It has wreaked havoc with the families. There is an enormous amount of family break up because of economic distress, there’s the opioid crisis. So we have to be sensitive,  there’s no simple federal program that’s going to reweave the social fabric of communities. But we believe there are steps we can take. We talk about place-based economics, where we have to pay attention to the fact that there are vast differences in certain kinds of prosperity in the different metro areas. There are certain communities, in western Pennsylvania for example, that have totally been undercut by the decline of the steel industry. We have to have policies and individuals to help them lift themselves up. But we also have to help these communities rebuild themselves. You cannot rebuild every community back to where it once was. But I think you can help communities be far better off, and have a much richer collection of local initiatives than they have now. The last is, empathy is sort of how we talk about politics. I’ve said for a couple of years now that if I wore a hat it would say ‘Make America Empathetic Again.’ We have a lot of difficulty understanding the problems of people we don’t agree with. Empathy is not something about looking down on others. Empathy is across lines. It’s not about the rich being nice enough to help the poor.

there’s no simple federal program that’s going to reweave the social fabric of communities. But we believe there are steps we can take. We talk about place-based economics, where we have to pay attention to the fact that there are vast differences in certain kinds of prosperity in the different metro areas. There are certain communities, in western Pennsylvania for example, that have totally been undercut by the decline of the steel industry. We have to have policies and individuals to help them lift themselves up. But we also have to help these communities rebuild themselves. You cannot rebuild every community back to where it once was. But I think you can help communities be far better off, and have a much richer collection of local initiatives than they have now. The last is, empathy is sort of how we talk about politics. I’ve said for a couple of years now that if I wore a hat it would say ‘Make America Empathetic Again.’ We have a lot of difficulty understanding the problems of people we don’t agree with. Empathy is not something about looking down on others. Empathy is across lines. It’s not about the rich being nice enough to help the poor.

PHAWKER: Can you explain briefly some of the proposals you make in the book such as the Charter for Working Families, G.I. Bill for American Workers, Contract for American Social Responsibility?

NORM ORNSTEIN: Among the things that we believe to get focused now is a whole set of policies that can not only unite more broadly the progressive movement, but reach across the lines, and those are—it’s partly a recognition that the economic inequality that we’ve had building for a substantial period of time, that affects working class and middle-class people—and notice I didn’t say white working-class people—it affects all working class people. All of this requires repair, and that repair has to come from a set of policies that will in the largest sense, and this is true if we are dealing with working families or workers themselves, fulfilling what we believe is a broad social contract that has united the country and given us prosperity in the past, and that is, if you have jobs and go to work, and do what you’re suppose to do, and you’re working the 40 hours a week, that in return you will get something approximating a living wage which means you will be able to have some kind of at least roof over your head for you and your family, you will be able to put food on the table, and will be able to have medical care if and when it is required, and you will also be able to strike some sort of work-family balance when you are having a child or a family member suffering from illness, or the like. And we also recognize that all this has to be done in the context of a different economy, including taking into account the ?gig-economy, which is the type of jobs that are not traditional ones—may be working from home, might be being an Uber or Lyft driver, and so on—that have a different set of requirements for the system that has been built around people who have been working for companies that provide health insurance, that have a structure in place. At the same time, we believe that the gulf that economic inequality creates or represents also has been exacerbated by the behavior of corporate America, driven especially in the last 30 years or so by nothing more than the single-minded drive for shareholder value as it’s called or maximizing quarterly profits. It doesn’t take into account a lot of other things including the long-term future of a company, much less the social responsibility that is there for a company. To put it in simple terms: sixty years or so ago, when Charles Wilson, the CEO of General Motors, testified that what is good for GM is good for America and vice versa—a clear indication that a company couldn’t prosper unless American prospered, that’s been gone. Now is what’s good for GM is good for GM. And these are now global companies. So it calls for changes in corporate governments to restore some value there.

PHAWKER: There’s a debate going on in the Democratic Party right now about the way  forward, and that is identity politics vs. economic populism. Most people seem to see this as an ‘either or’ proposition. What are your thoughts on that?

forward, and that is identity politics vs. economic populism. Most people seem to see this as an ‘either or’ proposition. What are your thoughts on that?

EJ DIONNE: In writing this book, we had a lot of conversations with each other about this. We very much think that this is a false choice. All politics is identity politics. Class politics is a form of identity politics. The notion that progressives should walk away from a concern for civil rights or a concern for African Americans or immigrants, that just makes no sense morally or politically. But what we do need is a politics that cuts across these lines in saying that many of the problems faced by African Americans and Latinos are similar to problems faced by working class people in Reading and Eerie. That many of the policies in Reading and Eerie would also help African Americans and Latinos, we think that’s a false choice. I like to point to the civil rights march of 1963. The slogan of that march was ‘Jobs and Freedom.’ What that slogan says is that economic empowerment and economic justice go hand in hand with racial justice, civil rights, and equality. We’ve got to sort of revisit that kind of politics. When I talk this way, some of my friends say I’m re-indulging my Bobby Kennedy fantasy. Bobby Kennedy famously appealed simultaneously to white working class voters and African Americans. But that’s not a fantasy, it happened before. FDR succeeded in doing this. Barack Obama lost in the white working class, but across states that he needed like Pennsylvania, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Ohio he got a very significant white working class vote. So you can have this kind of politics that reaches across class without denying that different groups have particular problems that we have to address.

PHAWKER: The Trump Administration is floating a $700 billion Pentagon build-up and many have pointed out that $700 billion is roughly what it would cost to make public higher education free in America to anyone who wanted it.

EJ DIONNE: Right, it’s an old guns and butter trade off. That’s true. Again it’s this conundrum about are people really anti-government or just anti-certain parts of the government and very much in favor of other parts of the government. The truth is, Barack Obama was going to have some kind of military modernization that was going to cost money, and you can still have a strong military and still have the resources to pay for college. But what is troubling is that people who point to the deficit and say ‘Well we’d like to do that but we can’t’ when it comes to education never point to the deficit when it comes to the military and never point to the deficit when it comes to tax cuts. That sounds to me like their concern about the deficit has nothing to do with what they’re saying, it’s simply a cover to favor some kinds of programs and oppose others.

PHAWKER: Is it false hope to believe that the Mueller investigation is going to somehow  make all of this right?

make all of this right?

NORM ORNSTEIN: Yes it is and one of the things we need to keep in mind here is that this is not just about Trump, this is about trump-ism. And this is about a whole series of factors—those that lead, going back many decades, to the decline of community, that sense of common purpose, that really began, it was heralded by the famous book Bowling Alone by Robert Putnam, but also by a number of sociologists like Robert Nisbet and Ky Ericson who pointed to it several decades ago. Leading up to the yawning economic inequality and the sense of great pessimism in the country about the future that people felt for themselves or for their children, and then including the partisan tribalism and the negative partisanship and what we would view as the radicalization of a republican party that went from being a center-right party with a significant number of moderates, to a right-right party in which the tension is not between the center and the right or the moderates and the conservatives but between the conservatives and the more radical ones. None of those things go away, and the tension that we have on racial grounds as our country has become more diverse and as we’re heading inexorably towards a country where whites and especially, a book on the end of white Christian America, points out, white Christians will no longer be in the majority—that has created its own set of discontents and tensions and those things don’t disappear if Trump is no longer president. Mike Pence is different, he has a different personality, he is less likely to get us into a nuclear showdown with North Korea, he doesn’t have the same issues with kleptocracy, he’s not likely to use racially driven or combustible rhetoric. But he also, unlike Trump, is very much an ideologue, at to look at the policy process and outcomes that Pence would like to see, you just have to look at the cabinet members that are his choices, and that starts with the budget director, Mick Mulvaney and goes to Tom Price and Ryan Zinke and Scott Pruitt, you are going to have a series of outcomes on social policy and role of the federal government and government spending, that are going to be very controversial and in many cases destructive.

PHAWKER: And lastly, from the vantage point of today, September 2017, what is your prediction for the outcome of 2018?

NORM ORNSTEIN: Well the first answer is we just don’t know at this point because events will make a difference. It’s clearly going to work to the detriment of republicans and that is because of the natural rhythm we have in our midterm elections. I don’t think we’re likely to see the kind of wave  that Trump’s approval numbers, or the ineptitude of republicans in congress would lead you to have otherwise, and that’s because what normally happens is the president’s party is divided and demoralized, they tend to stay home more and the opposition party is angry and upset and they tend to get out and vote. But since we’re so driven by negative partisanship, we may see a more robust turnout of republicans who are just determined to keep democrats from having any more clout, as we know it, as they would see it. So the differential in turn out may be a bit less, we may have more laws that restrict voting, we may have more Russian interference—there are things that we just don’t know. That’s one reason why us who are following these things keep a close watch on the upcoming 2017 elections for governor and state offices in particular in New Jersey and Virginia, and that may give us a clue.

that Trump’s approval numbers, or the ineptitude of republicans in congress would lead you to have otherwise, and that’s because what normally happens is the president’s party is divided and demoralized, they tend to stay home more and the opposition party is angry and upset and they tend to get out and vote. But since we’re so driven by negative partisanship, we may see a more robust turnout of republicans who are just determined to keep democrats from having any more clout, as we know it, as they would see it. So the differential in turn out may be a bit less, we may have more laws that restrict voting, we may have more Russian interference—there are things that we just don’t know. That’s one reason why us who are following these things keep a close watch on the upcoming 2017 elections for governor and state offices in particular in New Jersey and Virginia, and that may give us a clue.

EJ DIONNE: You know, I actually think that all journalists and all analysts should take about a three year fast from making predictions after the last election. I truly admit I did not expect Trump to become president. I was right, because I never thought he would win and he didn’t win the popular vote, most Americans voted against Trump, but he got there. If you look at it right now analytically, on the one hand Democrats face some real hurdles because the Senate seats that are up in 2018 put Democrats far more at risk than Republicans. It will be a challenge for them to win the Senate, it will hard to keep the ten seats they have in the states carried by Trump. In the House you’ve got the gerrymandering that gets in the way. And there are seats that Hillary Clinton carried that are held by Republicans but not all of them will be easy to win. But if you look at the number right now, and if you look at Trump’s popularity or lack there of, the numbers are looking really quite good for Democrats. Because of the gerrymandering the Democrats need to win the total vote in House races by something like five or six percent. So they need a big win in order to eek out a majority in the House. Right now they’re in striking distance of doing that. And that’s about as far as I will go in making any prediction.

EJ DIONNE & NORM ORNSTEIN @ THE FREE LIBRARY TUE. OCT. 10TH @ 7:30 PM