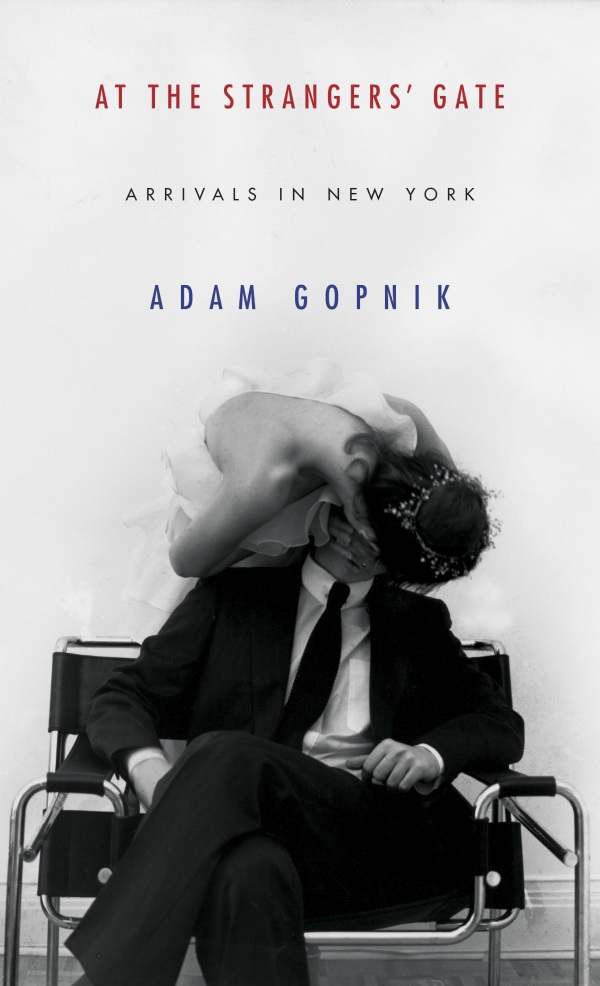

Photo by BLAKE GOPNIK

It’s a classic story: local boy, born and bred in West Philly, moves to New York at the dawn of the bombed-out, post-punk ‘80s with gal pal/fiance seeking fortune and fame as Art Garfunkel’s songwriter*, fails miserably, weathers marginal employment and postage stamp-sized apartments, grumpy art snobs and kooky magazine editors, plumbs the Platonic ideal of summer shirts for the pre-initialized Gentleman’s Quarterly, befriends Richard Avedon, Jeff Koons and Robert Hughes, cracks the genetic code of Talk Of The Town pitches, lands New Yorker staff gig plus book deal, and a rent-controlled SoHo loft lease, marries, procreates, publishes well-received collections of essays and criticism and novels for children, wins National Magazine Award three times, wins a George Polk Award, moves to Paris where, eventually, he is awarded the French Republic’s Chevalier de l’Ordre et des Lettres medal, whose previous recipients include William Burroughs, Rudolph Nureyev and Ang Lee. Nearly all of which is relayed with generosity, drollery and vividly-observed mis en scene in At The Stranger’s Gate by the man who lived it, Adam Gopnik, arguably one of the most elegant and evocative prose stylists currently scribbling. In a homecoming of sorts, Mr. Gopnik will discuss his new book at the Free Library on Friday. (For more on his Philly back story, check out our 2011 Q&A.) On Wednesday, writing from Paris, Mr. Gopnik responded to our questions via email:

PHAWKER: One of my favorite lines in the book is: “In an era of cocaine and punk we were champagne and Gershwin.” Can you unpack this a bit for readers? (Also, I love the fact that you got married in ripped jeans and a suit jacket)

ADAM GOPNIK: WELL, we arrived in New York in rhapsodic love with the great songs and  songwriters of the earlier, pre-rock dispensation: Rodgers & Hart and the Gershwins and Harold Arlen and the rest. This wasn’t as commonplace then as it is now, when even Rod Stewart records “The Great American Songbook”. (Not that I wasn’t a rock aficionado of a kind; you recall our dissection of when it was exactly that Jimi Hendrix played the Electric Factory and I saw him. But by twenty something my tastes had altered.) That’s why we called our tiny basement apartment “The Blue Room”, in honor of that song, which I had heard on the Ella Fitzgerald R&H songbook (at that moment still only available as an LP in England!) . . So a certain dream of a lost , lyrical New York – a New York you could hear at the Café Carlyle (not that we could afford it) or still glimpse at Bradley’s, downtown – represented by sad and swinging music, was at the heart of our vision of the city. When we met, and were spiritually adopted much later by the photographer Dick Avedon, this vision suddenly seemed plausible – he came from that time, yet was still very much of this time, and his favorite tipple, from his years in France, was champagne. We got that habit, and still have it. It’s cheaper than coke, and I suspect more beautifully labeled. ((Good for the digestion, too.) Anyway, that image of life was central to us, however anachronistic—and one of the joys of life is discovering that anachronisms are yours to end with enough reviving energy. You take the curse off ‘nostalgia” by living it intensely.

songwriters of the earlier, pre-rock dispensation: Rodgers & Hart and the Gershwins and Harold Arlen and the rest. This wasn’t as commonplace then as it is now, when even Rod Stewart records “The Great American Songbook”. (Not that I wasn’t a rock aficionado of a kind; you recall our dissection of when it was exactly that Jimi Hendrix played the Electric Factory and I saw him. But by twenty something my tastes had altered.) That’s why we called our tiny basement apartment “The Blue Room”, in honor of that song, which I had heard on the Ella Fitzgerald R&H songbook (at that moment still only available as an LP in England!) . . So a certain dream of a lost , lyrical New York – a New York you could hear at the Café Carlyle (not that we could afford it) or still glimpse at Bradley’s, downtown – represented by sad and swinging music, was at the heart of our vision of the city. When we met, and were spiritually adopted much later by the photographer Dick Avedon, this vision suddenly seemed plausible – he came from that time, yet was still very much of this time, and his favorite tipple, from his years in France, was champagne. We got that habit, and still have it. It’s cheaper than coke, and I suspect more beautifully labeled. ((Good for the digestion, too.) Anyway, that image of life was central to us, however anachronistic—and one of the joys of life is discovering that anachronisms are yours to end with enough reviving energy. You take the curse off ‘nostalgia” by living it intensely.

PHAWKER: Another great line: “the rancid ambitions of Julian Schnabel.” If I recall correctly, that wasn’t you saying it, let the record show, but can you briefly speak to the fact that in New York bohemian circles in the early 80s, ambitious people had to mask their ambition for fear of being designated inauthentic or insincere. Seems to me that young people of a similar station these days feel no need hide the fact that they want go places, as it were. That anxiety about authenticity doesn’t seem to bedevil artistic youth of today the way it did previous generations. Why do you think that is?

ADAM GOPNIK: I don’t recall who I’m quoting there, or whose position its characterizing. Certainly, not my own; his ambition was no more rancid than mine. As to the larger question, I’m not sure it’s so…sometimes I have the sense that we could pursue our ambitions with less guilt – or just more plausible hopes – than twenty somethings can now. But certainly, thirty plus years in which the parody of the thing has become indistinguishable from the thing, and in which the whole idea of ‘selling out’ seems like an incomprehensible ambition (who would you sell out to, now, if you were a young writer?) has made authenticity seem quaint, not to say juvenile. In fact, you rarely see the word out of scare quotes:”authenticity”. Any display of worldly ambition was frowned on in artistic circles in the fifties; the wrong display was frowned on the sixties; now no one can tell the display from the art. That may be too cynical. But it doesn’t feel wrong.

PHAWKER: You talk about how back then you could more or less blunder into cool jobs and you mention that early on your wife got a job as D.A. Pennebaker’s archivist. As an avowed Dylanphile and Bowie freak, hoping you might be able to tell of intriguing footage from Don’t Look Back and/or the Ziggy Stardust doc that never made the final cut.

ADAM GOPNIK: Would that it were so! My memory suggests – and now Martha herself confirms from the other side of the room – that while there was a lot of unused footage from those great films, it was mostly left on the cutting room floor because it was less vital than what went in. Generally speaking, things left out of art are left out for a reason – ‘recuts’ are often fascinating, but rarely better than the original. (See Apocalypse Now Redux) What is funny is that there was a piece in the Times just a couple of years ago about the Pennebaker Archive, and they’re still ongoing — now thirty plus years! — attempts to organize it. Apparently, it is the Augean Stable of documentary; each generation must try and cleanse it.

PHAWKER: *You write amusingly about trying unsuccessfully to sell a song to Art Garfunkel via an informal network of proxies. What can you tell us about that song? Did you ever get any feedback on the song from Mr. Garfunkel?

ADAM GOPNIK: No, I never got the cassette back, or heard a word. But I did eventually begin to write songs professionally: my musical show, The Most Beautiful Room In New York, with music by David Shire and book and lyrics by me, debuted at the Long Wharf Theater in New Haven  in April, and had a satisfying month long run. We’ll see where it goes next. Nothing in my creative life makes me prouder than that Shire-Gopnik score.

in April, and had a satisfying month long run. We’ll see where it goes next. Nothing in my creative life makes me prouder than that Shire-Gopnik score.

PHAWKER: You talk about your decades long friendship/mentorship with photographer Richard Avedon and mention that other friends had similar relationships with William Maxwell and Nora Ephron and an unnamed ‘great movie critic.’ Can you ID this critic and share an interesting aside about your friend’s relationship with him/her? And speaking of Avedon, I see that the amazing photo on the cover of the book was shot by Blake Gopnik, who I am assuming is a relation. Can you talk about that photo — is that you and Martha — how came about and why it was selected for the cover?

ADAM GOPNIK: The movie critic was simply David Denby, who has written movingly in The New Yorker about his adoption (and eventual disowning) by Pauline Kael. I’m not sure why I didn’t name him – perhaps because that relation brought The New Yorker into the conversation in a way that distracted from the larger point. Almost all of the other protégés were taken up, turned around, and never rejected; David, by his own account, had a more dramatic exchange.

The kissing couple on the cover is indeed us, and was indeed shot by my brother Blake on the day of our wedding – not our official city hall wedding in New York, but our decorative wedding the following summer in Montreal – and he was working very much under Avedon’s star, that white background and black and white graphics, though of course without ever having met him. It was Martha who made the photo, though. In the rest of the series we were beaming innocently at the camera [SEE BELOW, RIGHT], and then she suddenly reached over and kissed me, passionately, for what still seems no good reason. As I say in the text, I thought at that moment, I don’t deserve her; her mother thought, He doesn’t deserve her, and Martha may have thought, No one deserves me, but at least he has a destination. When Chip Kidd, the designer, came to root through our old pictures in search of material for a cover collage, he saw that and said, “That’s the cover.” “This with other things?” I suggested. No, he said. Just that. Obviously, he was right. I like the fact that it is both entirely us, and entirely anonymous. It’s us, but could be any young couple starting life in nice clothes and love.

PHAWKER: Given your background in art history, and long friendship with Robert Hughes, I feel like you are a good person to ask this question: Does that fact that Jeff Koons entire body of work makes my skin crawl make me a bad person? (And let the record show I love/’get’ Duchamp and Warhol)

ADAM GOPNIK: Well, part of the point of Koons’ work is to make your skin crawl. I think Peter Schjeldahl once started a piece in praise of Koons saying “Jeff Koons makes me sick.” Warhol crossed the now innocent looking line between demotic imagery and high art; Koons crossed the line between kitsch and Warhol. He fascinated me then, as he does now, because he was genuinely committed to his own kind of craziness, not a smooth operator but an obsessive. And what obsessions! All I can say is that when one looks at his famous metallic bunny of the eighties, it is, exactly, the demon of Trump Tower. He trapped his time; a wiser artist might have trapped less.

PHAWKER: As someone who has worked most of his professional life in publishing (both book and magazine) in one capacity or another, can you share your thoughts about the state of the business, where you see things heading and what advice re: all that you would offer to young writers just starting out?

ADAM GOPNIK: As I wrote not that long ago, there has never been a time when it has been easier to be a writer, never a time when it has been harder to be a professional writer. I’ve had a series of brilliant apprentice-assistants in the past decade, and all of them, mostly young women, have set out to make lives in the writing world – and have by and large succeeded, though not without perhaps more dead end frustrations than my generation knew. (The very fact of so many ‘internships’ is dubious. I worked at dumb jobs, but never ‘interned’.) Malcolm Gladwell’s famous ‘ten thousand hours’ really breaks down to six years of effort – and I think that six years of steady effort in the literary world will be rewarded, perhaps not with the job or publication of your dreams, but at least with some job near that job, some publication close to the dreamt-for one. No one asked us to write, remember, and so in a sense even a professional life as fortunate as my own has to be accepted as a thing given , not earned, or not entirely earned — perpetually on loan from the muses, who may call it back at any time and give it to the as fortunate as my own has to be accepted as a thing given, not earned, or not entirely earned — perpetually on loan from the muses, who may call it back at any time and give it to the next guy, or girl.

ADAM GOPNIK @ THE FREE LIBRARY FRIDAY SEPTEMBER 22ND 7:30 PM $15