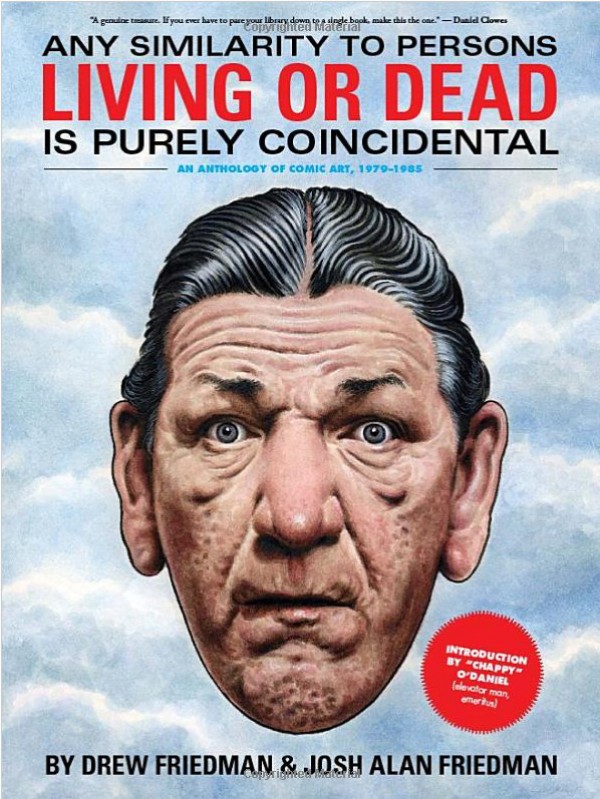

Illustration by DREW FRIEDMAN

SPY MAGAZINE: To artists and intellectuals, the twentieth century has posed no questions more vexing than these: First, can art make sense of the Holocaust? And second, why do the French love Jerry Lewis? The first question can’t really be answered, at least not in the space allotted here. As for the second, it’s my own opinion that the French have confused sloppy, uneven filmmaking with Godardian anti-formalism. Regardless, raising these two issues on the same page is not just a pointless exercise in non-sequitur. Because Jerry Lewis, like Elli Wiesel and Primo Levi before him — not to mention the producers of the NBC ministeries Holocaust — has transformed the incomprehendible into art.

He did this two decades ago, in 1972, a year of cultural ferment that also saw a black man, Sammy Davis Jr., snuggle Richard Nixon on national television. It was Lewis’ 41st film (but his first to deal with the mass destruction of European Jewry), and it turned out to be the most notorious cinematic miscue in history — unfinished, unreleased, said by the few who’ve seen it to be almost unwatchable. Oh, there are also Von Stroheim’s Queen Kelly and Welles’ Don Quixote, among other busts. But no other film, seen or unseen, can boast both Nazi death camps and the auteur responsible for The Nutty Professor. There is only one The Day the Clown Cried.

Were it ever released, the film would surely provoke as great a stir as a rediscovered Balanchine ballet or an unearthed Van Gogh — if not on the pages of the Arts & Leisure section, then at least among scores of sitcom writers, apprentice film editors, clerks in comic book stores, and others who are expected to wear high top sneakers to work and whose fascination with Jerry Lewis transcends easy irony. But so far, The Day the Clown Cried hasn’t surfaced, and it likely never will. Only a handful of people have ever seen it. And as they grow older … To preserve their memories for future generations, SPY has tracked down and recorded the impressions of eight people who have seen The Day the Clown Cried or who participated in it’s creation. You and I may never watch in mute wonderment as the lost gem lights up the screen before us, but now, at least, we can know what it felt like for those who were there. But first, the back story. MORE

BBC: The Day the Clown Cried told the story of a fictional clown, Helmut Doork, who was thrown into prison and eventually used to entertain children and lead them into the concentration camp gas chambers. Lewis – at the peak of his career after success in The Nutty Professor and the Bell Boy – wrote and directed the film, and was at first very passionate about the idea. But perhaps even he eventually found the subject matter too harrowing. The film has never been released, with only a handful of people claiming to have seen anything from the production. Lewis himself avoids questions about it during interviews and public appearances. For the BBC documentary The Story of Day the Clown Cried, presenter David Schneider went to hear the stories of people close to the production, including the late Lars Amble, who played a Nazi guard. MORE

RELATED: What Is Spy?

RELATED: Drew Friedman (born 1958) is an American cartoonist and illustrator who first gained renown for his humorous artwork and “stippling“-like style of caricature, employing thousands of pen-marks to simulate the look of a photograph. In the mid-1990s, he switched to painting. His painstaking attention to detail and photorealistic parodies of Hollywood legends is widely admired. Friedman’s work has appeared in such periodicals as Entertainment Weekly, Newsweek, Time, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The New Yorker, The New Republic, The New York Observer, Esquire, RAW, Rolling Stone, The Village Voice and Mad. His works have been anthologized in seven collections, and he has illustrated a number of books, including Howard Stern‘s Private Parts and Miss America.

Although in recent years Friedman has mostly worked doing caricature illustrations for mainstream publications, he first attracted public attention in the 1980s producing morbid alternative comics stories, sometimes working solo but often with his brother Josh Alan Friedman writing the scripts. These stories portrayed celebrities and character actors of yesteryear in seedy, absurd, tragi-comic situations. One memorable story followed Bud Abbott and Lou Costello wandering the urban jungle at night, encountering whores, junkies and other lowlifes. Friedman created strips featuring actor/wrestler Tor Johnson in his iconic hulking moron persona from Ed Wood, Jr. films. The brothers also wrote stories about talk-show host Joe Franklin, including one strip, written by Drew, for Heavy Metal, The Incredible Shrinking Joe Franklin, that prompted Franklin to sue for $40 million. The suit was later dismissed.[citation needed] These stories were generally meant to be amusing, although they were extremely dark and a few were tragic. Friedman’s work won high praise from such notable figures as Kurt Vonnegut Jr., who compared him to Goya,[citation needed] and R. Crumb, who wrote, “I wish I had this guy’s talent.” MORE