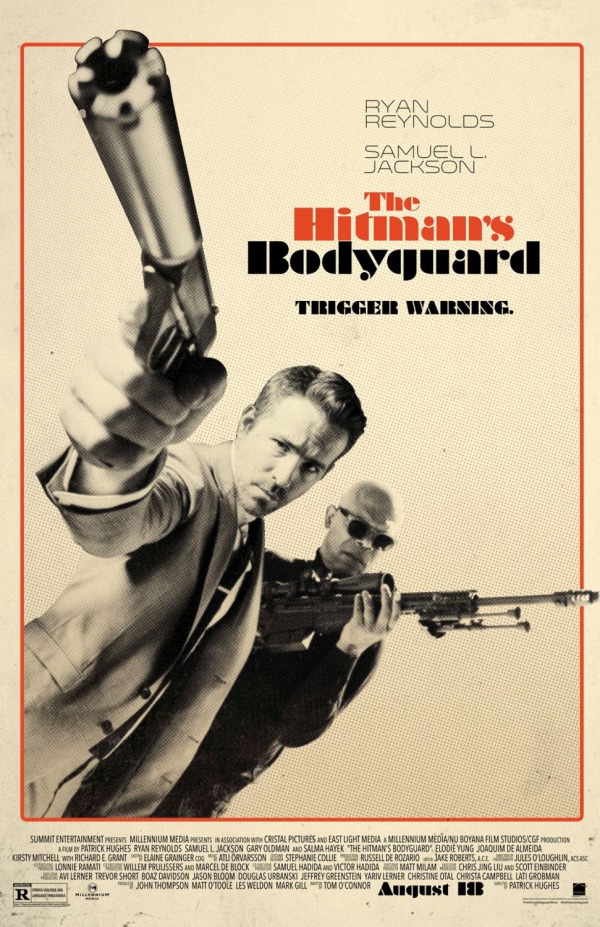

THE HITMAN’S BODYGUARD (dir. by Patrick Hughes, 118 minutes, USA, 2017)

BY CHRISTOPHER MALENEY FILM CRITIC Following in the tradition of buddy-cop action comedies like 48 Hours or 16 Blocks, The Hitman’s Bodyguard is the story of a material witness who must be transported to the courthouse overcoming multiple obstacles and people trying to kill him before he gets there. Where this movie differs from those archetypal comedies is in its international scale, because, instead of a drug dealer or corrupt cop, the authority figure on trial is Gary Oldman’s Vladislav Dukhovich (a substitute for real life President of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko). Another difference is that neither of our heroes are cops. Instead, the witness is Samuel L. Jackson’s Darius Kincaid, an American contract killer of international renown. Though Interpol, Europe’s ‘most highly trained’ police, are incapable of protecting Kincaid due to a mole in their ranks, Ryan Reynolds’ Triple-A Rated protection agent, Michael Bryce is up to the task.

BY CHRISTOPHER MALENEY FILM CRITIC Following in the tradition of buddy-cop action comedies like 48 Hours or 16 Blocks, The Hitman’s Bodyguard is the story of a material witness who must be transported to the courthouse overcoming multiple obstacles and people trying to kill him before he gets there. Where this movie differs from those archetypal comedies is in its international scale, because, instead of a drug dealer or corrupt cop, the authority figure on trial is Gary Oldman’s Vladislav Dukhovich (a substitute for real life President of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko). Another difference is that neither of our heroes are cops. Instead, the witness is Samuel L. Jackson’s Darius Kincaid, an American contract killer of international renown. Though Interpol, Europe’s ‘most highly trained’ police, are incapable of protecting Kincaid due to a mole in their ranks, Ryan Reynolds’ Triple-A Rated protection agent, Michael Bryce is up to the task.

The duo are perfectly mismatched, with both Reynolds and Jackson playing roles they are deeply comfortable with. Darius Kincaid is a foul-mouthed, quick-thinking assassin who trusts his own instincts for his success. Michael Bryce is a meticulous planner whose plans are slowly brought to ruin by their enemies, and by Kincaid’s insistence that he doesn’t need any protection. And he’s right; the amount of gunfire he absorbs at close range is almost enough to break the suspension of disbelief, especially when balaclava wearing policemen are mowed down left and right. If it weren’t for God’s protection, the audience is led to believe, Kincaid would probably be dead. As it is, someone up there seems to be watching out for him.

I laughed, I cheered, I got carried away in the thrill of the thing, but something kept tickling my mind. What is this movie saying symbolically? Is there an intention to say anything, or is it merely happenstance? Because, for the past 70 years, America has been the military hegemony in Western Europe. Lately, however, there is a creeping fear of that position changing. Russia seems to be creeping in from the East. There is a call for more NATO countries to supply their own defense. What does it mean, then, that in this movie the International Criminal Court can only convict Dukhovich with evidence supplied by an American? What does it mean that Interpol can’t protect their man from Russian-speaking terrorists, but need to rely on an American private military contractor to provide security? Was this film bankrolled by the Pentagon?

But maybe I shouldn’t even worry about these things. It’s a bloody hilarious movie, with great pacing and an interesting meditation on violence as love, and the search for revenge. Sure I had a few gripes afterwards: I wasn’t sure why the Interpol mole had decided to become a mole besides the necessity of the plot, Salma Hayek’s character was only marginally more deep than the ‘angry Latina’ stereotype, and I felt the pendulum between ‘structural justice’ and ‘frontier justice’ swung a little too far to the frontier side of things. But the comedy hit all the right notes.