All photos by HENRY GROSSMAN except the final image by JOSH PELTA-HELLER

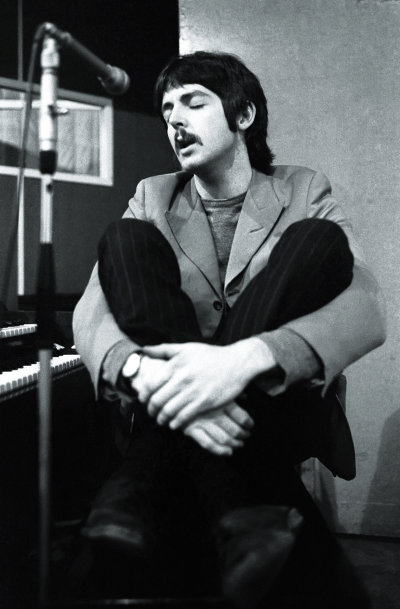

BY JOSH PELTA-HELLER In March of 1967, on assignment for Life Magazine, photographer Henry Grossman found himself sitting in EMI Studio Two at Abbey Road with The Beatles, while they sculpted and shaped the early demos of what would become “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds.”

“I remember when we walked in that Paul [McCartney] came over and said ‘hey guys, listen to this…,’” recalls Grossman fondly, “and he sat down at the piano and started playing something, and [the other three Beatles] all gathered around, and by the end of the evening they were working on “Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds.” It changed so much from the beginning. And what fascinated me was that, at one time George [Harrison] got up and went into the engineering room, and he started pulling out condensers from the array of machinery. ‘Bring this one down here, and this one over here,’ and that kinda thing.” Grossman observes, “They knew what they were doing, and playing with, and that was terrific.”

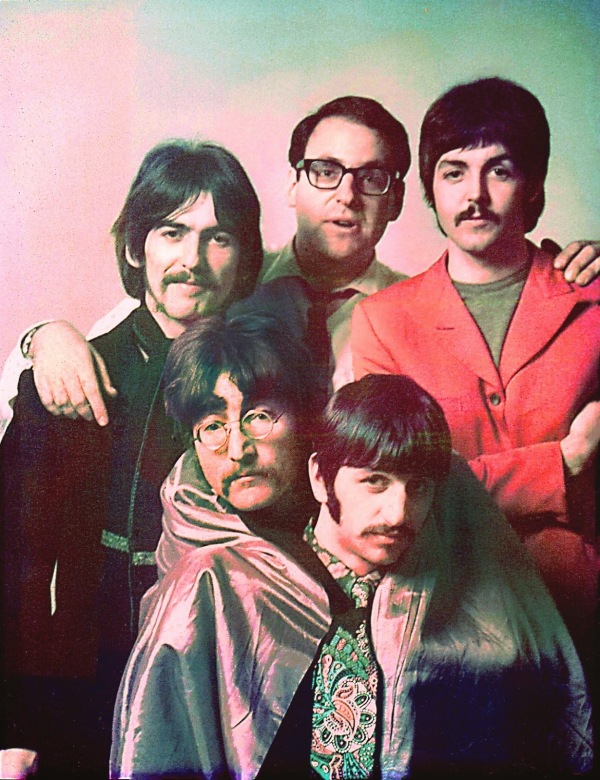

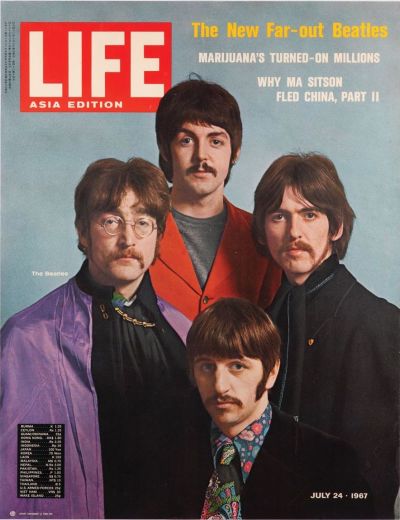

Grossman began to set up his strobe lamps and colored seamless paper backdrop on location at Abbey Road. A  young photojournalist just 31 years old, at that point, he would shoot that day what would become the iconic cover portrait for one of that year’s July issues of Life, the photograph that would come to be his most famous of the band: the four of them in their mid-twenties, mustachioed in those days, posed in a diamond configuration. “I wish I had been more informal,” regrets the photographer about the pose, with the introspective, self-critical analysis you’d have to expect from any real artist, as he considers some of the other experiments in photography concept and composition that he conducted with the Fab Four in their studio that day. “I was hoping to get something like ‘The Englishmen with their tea,’” showing me one of several rejected outtakes from the session. “It didn’t work; it doesn’t work.” he concludes dismissively,“You don’t know what’s going on. It’s just four guys drinking tea.”

young photojournalist just 31 years old, at that point, he would shoot that day what would become the iconic cover portrait for one of that year’s July issues of Life, the photograph that would come to be his most famous of the band: the four of them in their mid-twenties, mustachioed in those days, posed in a diamond configuration. “I wish I had been more informal,” regrets the photographer about the pose, with the introspective, self-critical analysis you’d have to expect from any real artist, as he considers some of the other experiments in photography concept and composition that he conducted with the Fab Four in their studio that day. “I was hoping to get something like ‘The Englishmen with their tea,’” showing me one of several rejected outtakes from the session. “It didn’t work; it doesn’t work.” he concludes dismissively,“You don’t know what’s going on. It’s just four guys drinking tea.”

Magnum Opus

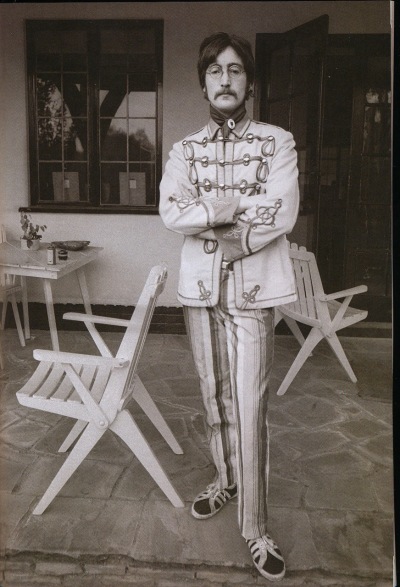

In June of 1967, the Beatles released their eighth studio record, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. The record garnered all the requisite contemporary industry accolades, including the dubious distinction of being the first rock LP to chalk up an album-of-the-year Grammy. Arts & Culture journalists spewed superlatives in exclamation, and roundly applauded what many considered to be a new bridge between popular and “higher” art forms, and the inception (or at least popularization) of “the concept record.” Accompanying all the new distinctions was a healthy share of antipathy and malaise, as well, with charges of pretentiousness, overproduction, and contrivance filed by irreverent, iconoclastic critics, by envious, outmoded or outshined contemporaries, and by Rolling Stones lead guitarists. It’s “a mishmash of rubbish,” groaned Keith Richards, in a recent interview. (Richards would notably go on that  year to help create the Stones’ mishmash of rubbish, Her Satanic Majesties Request, released just a few months later.)

year to help create the Stones’ mishmash of rubbish, Her Satanic Majesties Request, released just a few months later.)

The cultural influence and impact of Sgt. Pepper is impossible to deny, as we celebrated the milestone of its fifth decade, this past June 1st. Fifty years on, now, Sgt. Pepper remains one of the best-selling albums of all-time worldwide, and its iconic cover art and songcraft are recognized as among the most highly acclaimed and influential in music history. But whether you regard it as the Fab Four’s magnum opus or as their most overrated opus, statistically speaking it’s a safe bet that you’re probably a bigger fan both of The Beatles and of that record than Henry Grossman was when, in 1964, he was assigned by Time to shoot the young, fresh-faced Liverpudlians as they first performed on The Ed Sullivan Show.

“I’m an opera buff,” declares Grossman conclusively. “Even in college, I loved opera. So The Beatles were music I couldn’t hear. Now I can! But I was not really interested in that music [at that time].” He sums up. “It’s a fluke that I came away from The Beatles’ sessions with so much of my lifetime [defined by that work].”

As he reflects on his Pepper-session portrait, Grossman recalls his admiration for their ability to own their flamboyant fashion that came to define the era’s iconography. On the left side, John Lennon is draped with a bright purple cape, and above him Paul, at the pinnacle, in a red sports coat. George Harrison and Ringo Starr are wearing dark jackets accented by Ringo’s psychedelic-flavored collar and tie. “I was wearing a paisley tie, from Liberty of London,” Grossman recalls. “It was a very nice place, and it was a very sedate tie — I looked at the way the guys were dressed, and I said, ‘Ringo, I wish I had the guts to wear a tie like that.’ He came over and fingered my paisley tie and he said, ‘Well Henry, if ya did, it would still be Henry but with a bright tie.’ I never thought of that,” the photographer observes. (Although Grossman would at no point attempt any Beatle impressions as he narrates his recollections, you almost can’t help but hear Ringo deliver the punchline assessment in his trademark bass-baritone lazy Liverpool lilt.)

(Although Grossman would at no point attempt any Beatle impressions as he narrates his recollections, you almost can’t help but hear Ringo deliver the punchline assessment in his trademark bass-baritone lazy Liverpool lilt.)

“When I Was In London, I’d Go Visit”

Earlier this year, Henry Grossman warmly welcomed me into his West-Manhattan apartment — the home in which he and his sister were raised. He’s 81 now, but with a vital, commanding presence. A natural storyteller, he speaks with rich, sonorous voice, delivered with a measured and deliberate cadence that entreats you to lean in. For a couple hours that day, Grossman regaled me generously with vivid tales and spare, lucid memories of his colorful career as a professional staff photographer (back in the heydays of magazines when that job was a thing), and of the friendships he forged with John, Paul, George and Ringo, while he documented in images their mid-sixties metamorphosis from clean-cut pop stars to countercultural, genre-bending luminaries. To be sure, it was Grossman’s professionalism, artistry and craftsmanship that earned him assignment after assignment for the most widely circulated periodicals of the day: Life, Time, Newsweek, The New York Times. But to hear him tell it, it was largely the relationships he forged with the band that engaged and sustained his interest in The Beatles as the subjects of his prolific trove of photographs.

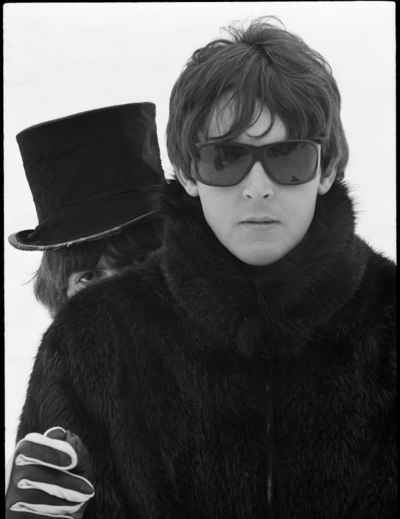

A year after the Sullivan Show assignment, Grossman would be asked to photograph the making of the film Help!, and to travel with the band, the film’s cast and crew, and director Richard Lester to document their production, from the palm-studded balmy beaches of the Bahamas and to the snow-covered Alpine slopes that famously set the scene for the “Ticket To Ride” music video that ultimately anchored the film. “The Daily Mail called me and said, ‘can you go to Nassau for a couple days? Our editor  is going to interview The Beatles.’ They were the big thing.” remembers Grossman of the auspicious assignment. He recounts the story for me with humility, and endearingly narrates this part as almost transactional. “I spent a couple days down there. And then I brought the stuff back to New York, had it developed, showed it to Life Magazine before I sent it to London, and Life Magazine said ‘go back!’ So I went back! I went to Nassau, and then I went to Austria with them.”

is going to interview The Beatles.’ They were the big thing.” remembers Grossman of the auspicious assignment. He recounts the story for me with humility, and endearingly narrates this part as almost transactional. “I spent a couple days down there. And then I brought the stuff back to New York, had it developed, showed it to Life Magazine before I sent it to London, and Life Magazine said ‘go back!’ So I went back! I went to Nassau, and then I went to Austria with them.”

It was there that Grossman started to become close with the band. “What happened when we were in Austria,” he remembers, “I became more friendly with George for some reason, and George asked me, ‘Henry, when we go back to England, can you do some portraits of Patti [Boyd] and me?’ And I went over there, and he said, “Hey, let’s go visit John!” He was five or ten minutes away, and we went over… “ He interrupts his own reverie to sum up, “I became a friend. And then thereafter when I was in London, I’d go visit.”

Grossman shows me one black-and-white image that he treasures from that time, on an occasion when Ringo would steal his camera to snap an image of the photographer sitting with the rest of the band, as he theorizes about how he managed to connect with them more so than perhaps any other photographer at the time. “I didn’t want anything from them. I was just trying to be one of the guys with them.” He continues, “the other thing was, I was only two or three years older than they were, maybe four years older, so we could relate. It was not a bunch of older photographers coming to photograph these ‘young whippersnappers,’” adding — in what may have been the understatement of the afternoon — “I was just there to see what was going on and to see if i could capture something.”

There Are Places I Remember

What he would capture during those four transformative years was some 7,000 images, the vast majority of  which would go unseen by the general public for decades to follow, apart from the images his editors at various magazines would select to feature. Finally, in 2008, along with some editing help from Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew, Grossman published Kaleidoscope Eyes, a concise collection of images from the day he spent with the band during the Pepper sessions. Four years later, the three of them collaborated again to publish what stands currently as the most definitive collection of his photographs of the Fab Four, a book called Places I Remember: My Time With The Beatles. Originally, as Grossman explained, they tapped him for a picture of Abbey Road [Studios] for a book they were putting together about the band’s recording gear. “A couple months later they said, ‘we’re coming to New York, we wanna talk with you.’ I said, ‘why?’ [They said,] ‘We wanna do a book!’” What the photographer describes next is enough to make any Beatles fanatic slowly close eyes and shake head from side to side: “‘I pulled out this pile of contact sheets that thick,” says Grossman, illustrating with his thumb and forefinger, “of pictures that, when Life Magazine gave back to me, I just put in a drawer. ‘Cause I was busy!”

which would go unseen by the general public for decades to follow, apart from the images his editors at various magazines would select to feature. Finally, in 2008, along with some editing help from Kevin Ryan and Brian Kehew, Grossman published Kaleidoscope Eyes, a concise collection of images from the day he spent with the band during the Pepper sessions. Four years later, the three of them collaborated again to publish what stands currently as the most definitive collection of his photographs of the Fab Four, a book called Places I Remember: My Time With The Beatles. Originally, as Grossman explained, they tapped him for a picture of Abbey Road [Studios] for a book they were putting together about the band’s recording gear. “A couple months later they said, ‘we’re coming to New York, we wanna talk with you.’ I said, ‘why?’ [They said,] ‘We wanna do a book!’” What the photographer describes next is enough to make any Beatles fanatic slowly close eyes and shake head from side to side: “‘I pulled out this pile of contact sheets that thick,” says Grossman, illustrating with his thumb and forefinger, “of pictures that, when Life Magazine gave back to me, I just put in a drawer. ‘Cause I was busy!”

The resulting edition weighs in at 17 lbs, including a black canvas clamshell that protects 528 silver-gilded, thick-stock pages featuring over 1000 of Grossman’s images. It’s so handsome that it inspires a reflexive impulse to look for gloves before you touch it. As a very limited run, copies of the tome can now be found starting at around $2500 from Amazon dealers. “I wish we had printed 2000 of these, or more,” Grossman lamented. “This book can’t be reproduced this way again, but I have more pictures!” He promises, “this is not everything.”

As we talk, I pore over the pages. Grossman interrupts his own recollections every so often to interject with some of the stories and contexts around specific shots, as they remind him, offering some connotations to take me on a narrated tour of the archive, and directing my attention to certain images to expressly define for me what he liked most about his favorites. It’s at this point in our conversation that I come to understand that, while the Sullivan Show and the recording of Sgt. Pepper were remarkable watershed moments that served to bookend Grossman’s document of The Beatles in the mid-sixties, it’s arguably the lower-profile and more intimate private moments to which he was privy which constitute the heart and soul of Grossman’s artistic and journalistic accomplishment with regard to his work with the band. The photographer himself is no stranger to that idea, and had been sort of guiding me, I realized, toward that conclusion.

expressly define for me what he liked most about his favorites. It’s at this point in our conversation that I come to understand that, while the Sullivan Show and the recording of Sgt. Pepper were remarkable watershed moments that served to bookend Grossman’s document of The Beatles in the mid-sixties, it’s arguably the lower-profile and more intimate private moments to which he was privy which constitute the heart and soul of Grossman’s artistic and journalistic accomplishment with regard to his work with the band. The photographer himself is no stranger to that idea, and had been sort of guiding me, I realized, toward that conclusion.

“Now that kinda stuff,” he stopped to remark of his work, “nobody else had that kinda stuff!” Grossman paused our perusal of his book to appreciate some tender images of the boys at home. By 1965, Grossman had become so close with the band, so trusted by them, that he was casually documenting their lives at home, images about which he recalls their manager Brian Epstein noted, incredulously, ‘we’ve never even allowed a British photographer into their homes!’ Here were dozens of beautiful black-and-whites of the the four young musicians at rest — engaging portraits of George and Patti, snapshots of John with his son Julian, Paul with his girlfriend Jane Asher, and Ringo with his wife Maureen. “I didn’t know that Maureen was pregnant at the time,” adds Grossman, “that’s why she’s covering her stomach in so many of the pictures.” These were images of the Beatles as family men, as fathers and boyfriends — a side of them that, up to that point, their management had been working actively to keep hidden from view, concerned that it would conflict with their marketing designs. “I got a call from Brian Epstein,” remembers Grossman, ‘saying ‘Henry, I’ve just seen these pictures, please don’t use those.’ Because they didn’t want the public to know [that they were in relationships]. He said, ‘I’ll make it up to you in another way later on.’ And then next day I got a cable from him — I still have the cable — saying, ‘Please disregard phone call. Can I have a set?’ And that was that.”

Reflecting on his relationships with The Beatles, the photographer emphasizes, “I liked them. And what I liked about them mostly was the authenticity, the simplicity and honesty, and the intelligence.” Grossman offers a contrast to illustrate this point. “I went to their first press conference here in New York, I loved it. But when The Rolling Stones came, I went to their press conference — I never went back. I didn’t like ‘em. They were smarmy,“ he sneers. “The Beatles, these guys, aside from the music — the fact that they’re wonderful musicians and they have formed the center of a musical universe for fifty years is terrific — that’s aside from who they are as people. There was an honesty and a simplicity and a directness — [and] the direct understanding of who they were and what was happening. Unusual and rare.”

“What else can I tell you?,” he asks, rhetorically.

Epilogue: Photographing the Photographer

“When you shoot me, you can shoot me sitting down, perhaps.” Following our conversation, I asked Henry  Grossman if I could compose a portrait of him somewhere in his home for this article, and he immediately offered his expertise with suggestions and stage direction. He posed in a corner, by a window, an area of his apartment naturally lit at that time of day with diffuse and ambient afternoon light. I start shooting. “Some without the glasses?,” he suggests.

Grossman if I could compose a portrait of him somewhere in his home for this article, and he immediately offered his expertise with suggestions and stage direction. He posed in a corner, by a window, an area of his apartment naturally lit at that time of day with diffuse and ambient afternoon light. I start shooting. “Some without the glasses?,” he suggests.

As a lifelong fan of the Beatles who’d once had Grossman’s work posted on my high school locker, I was eager to hear from Henry Grossman that day about the band from his perspective, from someone who’d had the extraordinary opportunity to document their lives and the spirit of their music, and to have shaped and filtered those images with an experienced and editorial eye. But as a photographer, I was eager to hear from him about just how he went about that. Celebrated portrait photographer Richard Avedon once admitted to Charlie Rose in an interview shortly before Avedon died that the thing he wrestled with most in his career — to date, he said — was often only having a few minutes to extract a subject’s personality in a portrait. I wanted Grossman’s take on that — how did he go about it?

“Look.” He offered. “Watch. I studied acting with Lee Strasberg, and I said at one point to Lee, ‘when I get nervous I start talking faster!’ And he said, ‘exactly the opposite. Go to base. Ground zero. Use your senses. Do you have your hands up? What’s the temperature like? Feel the pressure against your shoulder? Just concentrate on that.’” He summed it up as a function of mindfulness. “Really it is simply: Be Here Now. And once they’re there, then you can start talking to them.”

Grossman continued, “the other thing is, I was just looking through some pictures here, and I love it when people just look at you, and you can look into them. That’s where I start from.” He adds, “The storytelling is very important. What’s the context? What’s behind it?”