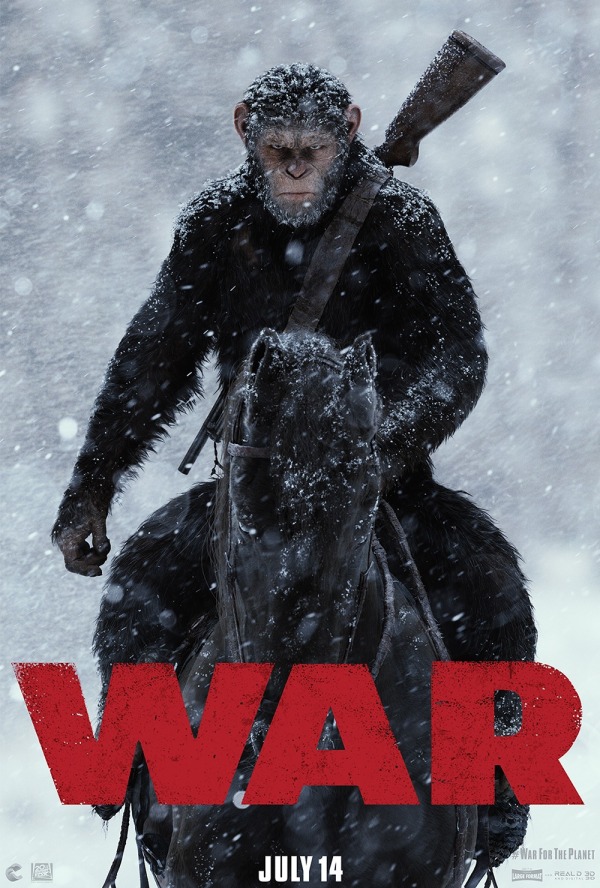

WAR FOR THE PLANET OF THE APES (2017, directed by Matt Reeves, 140 min, U.S.)

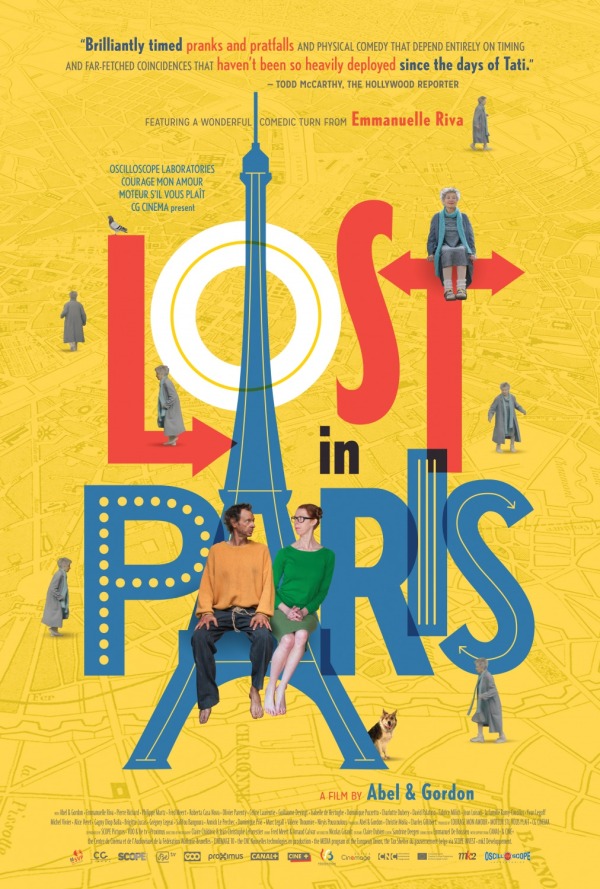

LOST IN PARIS (2016, directed by Dominique Abel & Fiona Gordon, 83 min, France/Belgium)

![]() BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC I remember how perplexed Charlton Heston’s Taylor was back in 1968 when he made the realization that the planet he and his men landed on was ruled by apes. As the third of the rebooted sequels touches down in blockbuster season I find myself similarly flummoxed by glowing reception of War For the Planet of the Apes, a terribly turgid, self-serious, gloomfest. Have the critics all exchanged brains with gorillas, like in the mad scientists films of the 1940s? If you loved the endless battles, one-dimensional characters and the over-written plotting of that recent Hobbit trilogy, I guess you’re in for CGI smothered treat. Me, I’m feeling like pounding the sand beneath the Statue of Liberty on some barren and rocky beach.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC I remember how perplexed Charlton Heston’s Taylor was back in 1968 when he made the realization that the planet he and his men landed on was ruled by apes. As the third of the rebooted sequels touches down in blockbuster season I find myself similarly flummoxed by glowing reception of War For the Planet of the Apes, a terribly turgid, self-serious, gloomfest. Have the critics all exchanged brains with gorillas, like in the mad scientists films of the 1940s? If you loved the endless battles, one-dimensional characters and the over-written plotting of that recent Hobbit trilogy, I guess you’re in for CGI smothered treat. Me, I’m feeling like pounding the sand beneath the Statue of Liberty on some barren and rocky beach.

How’d things go so wrong? The opening chapter, Dawn, back in 2011 got off to a fresh start, with James Franco bringing a human dimension to the story, a smaller-scale drama about the scientist responsible for first increasing the intelligence of our primate friends. By the end of the film it built to a climax of marauding chimps laying seize to downtown San Francisco and finally taking off across the Golden Gate Bridge for the wilds of Marin County (presumably taking over there one hot tub at a time.) Rise in 2014 found the apes struggling to live peacefully among humans, who are mentally regressing as a result of the same virus that is giving the apes increased intelligence. With War it’s the final showdown with an all-out conflict waged to decide whether ape or man will rule the planet.

The ape leader Caesar (content with his slave name?) is motivated to fight this battle by the easiest of all writer’s devices, the old “this time it’s personal” gambit after the murder of his wife and kids at the hands of The Colonel (Woody Harrelson shamelessly attempting to channel Brando’s Kurtz from Apocalypse Now). This opens the first of three acts, each pilfering a different genre. Before long Caesar and his rag tag crew are (semi-ludicrously) off on horseback for a old time western trip through the woods. Then Caesar is captured for a shout out to the prison movie genre and finally the climactic war movie finale, featuring extended battlefield action without strategy or creative staging, just ape to man clashes that hold out for a long as a CGI budget will allow. I miss that generation of film makers that fought in WW II and used the experience to try to convey the horror of war that they knew first hand. War on the other hand is part of the tradition that portrays war merely as violent, spectacular and oddly sterile. I don’t think the audience is well-served by this illusion.

The most interesting element about the film is the hand played by its makers that national disgust with the state of the nation and its citizens is so high that audiences will have no trouble siding against their species and rooting for the apes in this apocalyptic showdown. I think they made the right bet but the film doesn’t go very far in making us have mixed feelings about our extinction, the humans on view are a pretty unlikable bunch. Still, it’s a little shocking how quickly the film gets us to sell out of fellow Homo sapiens, maybe all that dismal climate change news has us convinced mankind’s fate is a lost cause anyway.

It seems that for many critics, Andy Sirkis’s motion capture performance beneath the Caesar animation is some kind of breakthrough. It all feels too deliberate to me, a sort of hyper-expressiveness that draws too much attention to itself to feel real. And the character himself, not conflicted, singularly motivated and as solemn as Moses in a silent Biblical epic, might be admirable but certainly not memorable. And like a silent melodrama, War has a young mute orphan on hand for extra poignancy and a secret identity to tie her to the ’68 original, just one of a handful of ways the film attempts to close the loop between the rebooted trilogy and its original Roddy McDowell-led franchise.

And what an oddball franchise the original was, with its groundbreaking make-up, weird pagan design and an avant score, holding together time travel, racial metaphors, an anti-nuclear bent and a violent revolution. This latest trilogy adds up to something much less, just the regular mundane bludgeoning these modern epics deliver, inhibited from doing anything truly daring on a 150 million dollar budget. At that price, War of the Planet of the Apes may deliver what audiences want but it lacks the imagination to deliver the originality the blockbuster genre so desperately needs.

_______________

If the widely-acclaimed Apes saga can’t thrill me, what does? At the expense of going full-on film snob, how about the French-Belgian comedy team of Fiona Gordon and Dominique Abel? In their fourth feature, Lost in Paris, the pair further refines their outrageously clever brand of physical comedy and ingenious production design, like a merging of the acrobatic skills of Buster Keaton with the handmade quaintness of Wes Anderson.

In their latest, Fiona (who resembles Pippi Longstocking’s geeky sister) is a Canadian librarian who comes to save her beloved and aunt from being forced into a retirement home (“I’m only 88!” she argues.) Stepping back for a selfie with the Eiffel tower, she falls in the Seine River and emerges without her back pack, penniless, wet and without her belongings. A homeless man (the slender dynamo Dom Abel) finds the backpack, changes into her clothes and then falls in love with her at first sight. Fiona is not interested but engages his help to find her runaway aunt as she lives the vagabond life in Paris.

Both Gordon and Abel have lovely, lanky bodies and the expressiveness of dancers as they awkwardly navigate a world that can plunge into near-disaster at any moment. Searching for Fiona’s lost aunt, the pair narrowly skirt death by drowning, falling, and cremation as they dazzle us with the intricate gags that fall into place so naturally. It would all collapse into its own whimsy if Gordon and Abel were not so brilliant with their comedic designs and their willingness to look into the abyss from time to time. Like their earlier films, Lost in Paris is both unique and personal while providing a connection to timeless talents like Chaplin and Jacques Tati that makes the film feel like a longtime classic. It’s a deliriously impressive feat.