BY JONATHAN VALANIA Populism ain’t what it used to be. The word has been hijacked by crypto-fascists, white supremacists and heartless neoliberal hatchet men who have warped its principles and perverted its meaning. Despite the torrent of media coverage saying otherwise, Donald Trump is NOT a populist. Marine Le Pen is NOT a populist. They are the wolves of bigotry hiding in populist sheep’s clothing. Bernie Sanders is a populist. Woody Guthrie is a populist. Bruce Springsteen is a very rich populist. More to our point, Creedence Clearwater Revival is populist. All those iconic songs in all their ragged glory that literally everyone loves are flannel-clad anthems for the working man — who was born on the bayou, who cleaned a lot of plates in Memphis, who pumped a lot of gas down in New Orleans, who was down on the corner, who was out in the street, who never saw the good side of the city until they hitched a ride on the Riverboat Queen, who were unfortunate sons running for their lives through the sultry jungles of Vietnam only to wind up stuck in Lodi again. Creedence Clearwater Revival wrote a song for everyone. They wrote a song for you, they wrote a song for me. They wrote a song for people long gone, and they wrote a song for people who haven’t shown up yet. But those songs will be waiting for them when they finally get here. Those songs — written, recorded and immortalized by four working class kids from El Cerrito — remain deathless classics enthroned on the highest reaches of the tower of American song. Now that, my friends, is true populism.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Populism ain’t what it used to be. The word has been hijacked by crypto-fascists, white supremacists and heartless neoliberal hatchet men who have warped its principles and perverted its meaning. Despite the torrent of media coverage saying otherwise, Donald Trump is NOT a populist. Marine Le Pen is NOT a populist. They are the wolves of bigotry hiding in populist sheep’s clothing. Bernie Sanders is a populist. Woody Guthrie is a populist. Bruce Springsteen is a very rich populist. More to our point, Creedence Clearwater Revival is populist. All those iconic songs in all their ragged glory that literally everyone loves are flannel-clad anthems for the working man — who was born on the bayou, who cleaned a lot of plates in Memphis, who pumped a lot of gas down in New Orleans, who was down on the corner, who was out in the street, who never saw the good side of the city until they hitched a ride on the Riverboat Queen, who were unfortunate sons running for their lives through the sultry jungles of Vietnam only to wind up stuck in Lodi again. Creedence Clearwater Revival wrote a song for everyone. They wrote a song for you, they wrote a song for me. They wrote a song for people long gone, and they wrote a song for people who haven’t shown up yet. But those songs will be waiting for them when they finally get here. Those songs — written, recorded and immortalized by four working class kids from El Cerrito — remain deathless classics enthroned on the highest reaches of the tower of American song. Now that, my friends, is true populism.

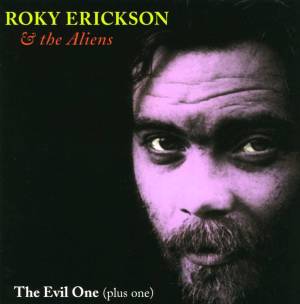

So when we got word that Creedence Clearwater Revisited, featuring the original CCR rhythm section of bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford, was coming to town I jumped at the chance to do an interview. In advance of Creedence Clearwater Revisited’s show at SugarHouse Casino on June 30th, I got bassist Stu Cook [pictured, below right] on the horn and let the Midnight Special shine an ever lovin’ light on me. DISCUSSED: What is a Creedence Clearwater Revival, what is a Goliwog, what is chooglin, how much CCR got paid to play Woodstock, why all the feuding with John Fogerty, how he wound up producing Roky Erickson’s horror-rock classic The Evil One, why all the suing of John Fogerty, Rusk Mental Hospital For The Criminally Insane, Hendrix, Apocalypse Now, The Grateful Dead, dope, the swamplands and bayous of the Bay Area, LSD, Ripple, and why — after decades of wrath, bitterness and acrimony and suing the shit out of each other — a Creedence Clearwater reunion is suddenly, albeit remotely, possible. After all, everything, even Hell, freezes over every few million years. And by my reckoning, we’re about due.

PHAWKER: Let’s just go back to the very beginning, all the members of Creedence grew up in El Cerrito, California. What was it like at that time?

STU COOK: It was a small bedroom community across the bay from San Francisco. It had a population of about 20,000.

PHAWKER: So you guys all meet up at the junior high school, correct?

STU COOK: Doug and I were in homeroom together and Doug met John and then the three of us got together. I want to say it was around ‘58.

PHAWKER: Wow, it was that long ago.

STU COOK: Yeah, we were in the eighth grade.

PHAWKER: And were you guys good pals back then or was it more just a musical relationship?

STU COOK: Doug and I were good friends and then we all got together musically and the three of us formed a band.

PHAWKER: Ok, and you guys were first called The Blue Velvets?

STU COOK: That’s right. Mostly we were backing up John’s brother Tom. We were an instrumental trio and whenever Tom needed a band, he hired us. Whenever his band was too busy to actually play music.

PHAWKER: The Blue Velvets hook up with Fantasy Records, which was a small indie label in the Bay Area. Fantasy wants to change the band name to the Golliwogs which you go with for a short period of time. (EDITOR’S NOTE: A Golliwog is the British equivalent of a pickaninny and likewise is now regarded as racially-insensitive and offensive if not straight up racist.)

STU COOK: We actually made a lot of records under that name.

PHAWKER: But you guys never liked the name?

STU COOK: No.

PHAWKER: Ok, and tell me about the origin of the name Creedence Clearwater Revival, to the best of your recollection, how did that come about?

STU COOK: Well, we were sitting around trying to come up with another name and Creedence was a guy that used to work with Tom, Clearwater was some kind of early ecological reference, and Revival referred to our personal commitment to try and become successful.

PHAWKER: But before CCR could release its debut, the band had to go on hiatus when John and Doug were drafted into the military?

STU COOK: John was in the army, and Doug was in the Coast Guard. Yeah, I’m not sure if the name change came after or before. I can’t remember. It’s got to be written or noted in some book somewhere exactly what happened.

PHAWKER: How did the Golliwogs evolve into Creedence’s sound? Was there a group discussion about pursuing this sort of psychedelic Americana sound?

STU COOK: Not really, that was just the music that we all gravitated to. So we always favored

Rufus Thomas, Otis Redding, and Booker T and the MGs over Pat Boone and other MOR generic pop artists. So, our roots were R&B all the time. Then John started writing songs with that kind of swamp imagery, if you will. So then we got labeled swamp rock.

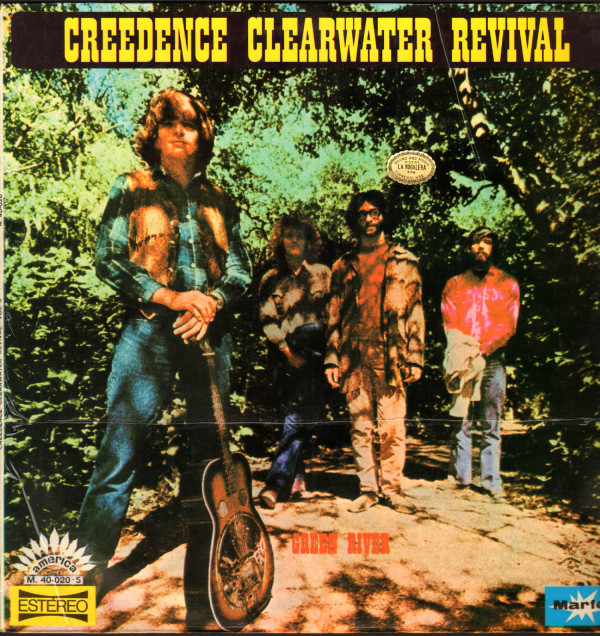

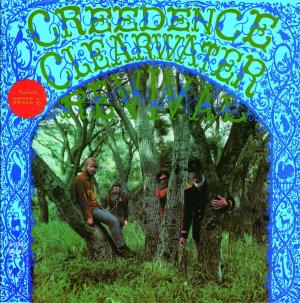

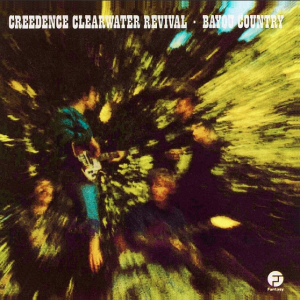

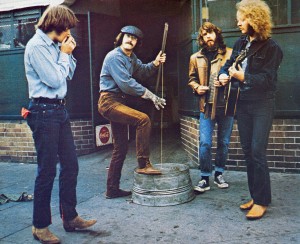

PHAWKER: And the band would pose for group photos in green lush environments that looked rather swampy. The first couple album covers were like that.

STU COOK: Well, the first one was right next to where we lived out in the country. Doug and I lived there and we rehearsed there. The second one was up in Mount Tamalpais somewhere and the third one was in the Charles Lee Tilden Memorial Park. The fourth one was down in Oakland right across the street from Fantasy Records.

PHAWKER: Which was the Willie and the Poor Boys cover?

STU COOK: Right. Fifth album, that was Cosmo’s Factory and that was inside of our rehearsal place.

PHAWKER: And Doug’s nickname was Cosmo, right?

STU COOK: Yup.

PHAWKER: Let’s go back to 1969. Let’s talk about Woodstock. My understanding is that John had  a relatively miserable time and was unhappy with the performance. I’ve read quotes where he described the crowd as “Dante-esque hellscape of entwined naked hairy mud-caked bodies as far as the eye could see.” What do you remember about that day?

a relatively miserable time and was unhappy with the performance. I’ve read quotes where he described the crowd as “Dante-esque hellscape of entwined naked hairy mud-caked bodies as far as the eye could see.” What do you remember about that day?

STU COOK: Did he really say that?

PHAWKER: I was paraphrasing him, but not exaggerating all that much.

STU COOK: What a jerk. Nobody understood just how great it was going to turnout or the fame and the whole thing about it. We got there and the weather turned bad. The fences lock came down so instead of a paid concert for a quarter million people, it became a concert for near a half a million people. They had no facilities for that many people — toilets, food, and whatever. They didn’t have anything, so people had to improvise and they actually pulled it off without any grief. Pretty amazing considering how much fun everyone was having.

You know, the weather was bad and caused the show to run late because of electrical issues so the place turned into a mudpit and people enjoyed it. They had a good time with it instead of pissing and moaning like somebody that we might not mention. We had a great performance. John was pissed off because the guys didn’t have the check for him the day of the show. So, other people got paid in cash when they said no money, no play. John wasn’t sophisticated enough to handle the situation. Anyway, he got into a fight with the Woodstock people and we subsequently got paid when the money came in, which wasn’t that long after the event.

John didn’t have a good time there. He told us that we played poorly and that we couldn’t be in the film. After all, we were number one in America at the time so it’s not like we needed it. As history has proven, anybody that was associated with Woodstock got a huge bump in their career. Further down the road, we got involved in the audio and we found a half a dozen tracks that were really strong. By then the ship had sailed, John told everyone that we blew and that we couldn’t be in it.

PHAWKER: Those tracks did end up on a later version of the Woodstock albums.

STU COOK: Yeah, we were on the 40th anniversary box set and there were fifteen minutes. “Keep on  Chooglin’” is a ten minute tune and there were two more. I think “Tombstone Shadow” and “I Put A Spell On You.” There’s going to be more Creedence at Woodstock released soon.

Chooglin’” is a ten minute tune and there were two more. I think “Tombstone Shadow” and “I Put A Spell On You.” There’s going to be more Creedence at Woodstock released soon.

PHAWKER: That leads me to another question that I wanted to ask you. How do you define ‘chooglin’?

STU COOK: I don’t know, just having a good time.

PHAWKER: Is chooglin’ sex?

STU COOK: Yeah, is sex having a good time? It’s kind of like saying, ‘What’s rock and roll?’ What part is the rock and vice versa?

PHAWKER: Just one more question about Woodstock. I’m curious, how much were you promised to get paid for this? I’m guessing by today’s standards that it’s going to seem like a paltry amount of money.

STU COOK: Either ten or fifteen thousand dollars.

PHAWKER: Well, that was a lot of cash back then.

STU COOK: Yeah, I think Jimi Hendrix got more, maybe The Who.

PHAWKER: Were you hanging with any of those folks?

STU COOK: We flew all night, our crew met us there with our gear. We didn’t really know any other people that were there the same day as us. Except the other people from the Bay Area. Bill Graham was there. He was a mentor to us and a lot of other Bay Area bands. He liked bands who delivered and didn’t like bands who didn’t deliver, so we were always pretty hard working. We always came to work straight and sober so he took a liking to us and always gave us advice. His people were there taking care of Santana, who I think got  about seven hundred dollars for the show.

about seven hundred dollars for the show.

PHAWKER: You cut out, did you mention The Grateful Dead?

STU COOK: No, I didn’t but John said that the poor crowd response was because we had to follow The Grateful Dead.

PHAWKER: The Dead put them to sleep.

STU COOK: Yeah, I remember that quote. It was also one in the morning by then, maybe later.

PHAWKER: Is that when you went on, one in the morning?

STU COOK: Yeah, we were supposed to play at ten. Because of the production problems because of the rain. There were a lot of safety issues too. We had minimal light because of that and it was hard to see the audience, but we could feel and hear them out there. I thought the effect was good. We played a journeyman set. The irony of this whole “you weren’t good enough to be there” is that every band only had one song. It’s just all nonsense.

PHAWKER: You mentioned showing up sober for gigs, to what extent did drug experimentation play in the creativity of the band, if at all?

STU COOK: None. It was just recreational for us.

PHAWKER: Were you guys stoners, were you guys into acid?

STU COOK: Yeah, but we were also drinkers. All of this wasn’t a part of the music experience though, it was more just individual experimentation. It was always welcome, but as a band we always approached it as a job. You had to be there on time and get it done as best we can. We also drank a lot of Ripple. We used to call it Rip-lay. Chateau Rip-lay. [laughs] Bayou Country, that album was largely fueled by Ripple.

PHAWKER: Ok, so I’m going to read you back a quote from John and I want to talk about the rift between John and the rest of the band. The quote is:

between John and the rest of the band. The quote is:

“I was alone when I made that [Creedence] music. I was alone when I made the arrangements, I was alone when I added background vocals, guitars and some other stuff. I was alone when I produced and mixed the albums. The other guys showed up only for rehearsals and the days we made the actual recordings. For me Creedence was like sitting on a time bomb. We’d had decent successes with our cover of “Susie Q” and with the first album. When we went into the studio to cut ‘Proud Mary,’ it was the first time we were in a real Hollywood studio, RCA’s Los Angeles studio, and the problems started immediately. The other guys in the band insisted on writing songs for the new album, they had opinions on the arrangements, they wanted to sing. They went as far as adding background vocals to ‘Proud Mary,’ and it sounded awful. They used tambourines, and it sounded no better.”

And he goes on to say that he gave you guys an ultimatum that he gets to do everything and make all the decisions and creative choices or he’s out. What’s your take on how things went down?

STU COOK: Well, that’s an awful lot of ‘I’ and ‘me.’ I would answer with a question: How many hits has he had since he got rid of the guys that were holding him back?

PHAWKER: Ouch, babe.

STU COOK: Look, it was a band. We all contributed. It’s interesting that one guy takes the credit for everything.

PHAWKER: You wrote your own bass lines right?

STU COOK: Yeah.

PHAWKER: The bass line or the drum beat is as integral to all those iconic CCR hits as the lyric or the melody. I think the old school definition of what constitutes composition needs to be updated to realistically reflect how these things work. I’ve played in bands, I’ve written songs and made albums in recording studios, so I know how it goes.

STU COOK: It’s always a little bit of this and a little bit of that and hopefully the best idea is  the one everyone gets behind. It’s not so much we sat around who had the last best idea and deciding whose turn it was. That’s not how you do things. John had ideas in his head as to how he wanted things to go, but we played the stuff and we played it the way that we interpreted it- regardless of how he wanted to say. The idea that is so important for some guy so many years later to say “I did this” or “I did that,” oh so what you’re saying is that you didn’t need those other guys. That’s why I always answer that question with my question. How many hits has he had since he got rid of the guys that were holding him back?

the one everyone gets behind. It’s not so much we sat around who had the last best idea and deciding whose turn it was. That’s not how you do things. John had ideas in his head as to how he wanted things to go, but we played the stuff and we played it the way that we interpreted it- regardless of how he wanted to say. The idea that is so important for some guy so many years later to say “I did this” or “I did that,” oh so what you’re saying is that you didn’t need those other guys. That’s why I always answer that question with my question. How many hits has he had since he got rid of the guys that were holding him back?

PHAWKER: I think the answer is actually one and a half. “Centerfield” and “Old Man Down the Road,” which is actually a thinly-disguised re-write of “Run Through The Jungle.”

STU COOK: That was 1985, that was the last one of the one and a halfs.

PHAWKER: I read somewhere that John made a decision without you guys about a tax haven that winded up being utterly disastrous and it ended up costing you guys millions of dollars of your own royalty money. Is this true?

STU COOK: In part. The actual details are a little blurred over time. John was acting as manager and was trying to get the band the better deal than the record company had promised us. The record company said, hey we have a better plan for you. So, they talked him and he convinced us into accepting this offshore tax haven. A tax situation that would eliminate federal income tax. In lieu of them paying us a decent royalty rate. At that point, Saul [Zaentz, Fantasy Records president] was kind of a mentor to John and John bought the story and of course the IRS had a different take on it.

PHAWKER: Didn’t Zaentz and his associates withdraw before the bank eventually dissolved along with your money as well.

STU COOK: That’s true.

PHAWKER: And then there was a series of lawsuits that eventually resulted in an $8.6 million payout to band members. Does that sound about right?

STU COOK: Yep.

PHAWKER: But despite the legal victory, very little of your money was actually recovered.

STU COOK: Well, no money was recovered. I think we got that money from the accountant’s insurance carrier.

PHAWKER: Oh, OK. So you did get paid.

STU COOK: Well, between that and the deal we cut with the IRS at a later date, we didn’t lose the money. We just lost the use of it for however many years.

PHAWKER: So, the band splits up acrimoniously and you all go your separate ways, but you do reunite briefly at Tom Fogerty’s wedding in 1980?

STU COOK: That’s right. We all got invited and went and there was a band playing at the reception and after a few beers we all got involved and played a bunch of tunes and…

PHAWKER: And?

STU COOK: It was like old times, it felt good. At least to me.

PHAWKER: John and his brother remained estranged even up until his death in 1990?

STU COOK: Yeah, that’s sad.

PHAWKER: I read that you and Doug Clifford and John Fogerty played your 20th high school reunion as The Blue Velvets?

STU COOK: Yeah, well who else were we going to be?

PHAWKER: Well, you could be Creedence minus Tom Fogerty.

STU COOK: Well, it was a high school reunion and they knew us as The Blue Velvets. That was just sort of a nod towards the good old days. We were The Blue Velvets when we were going to school so all the people there knew The Blue Velvets. Although they also knew us as Creedence, but that was many years later when we became Creedence.

PHAWKER: Creedence music has been used in a lot of things, but my estimation is that the most esteemed use of your music would be your version of “Susie Q” in Apocalypse Now. Would you agree?

STU COOK: No, that wasn’t even us playing.

PHAWKER: Oh right, it was a cover wasn’t it?

STU COOK: Basically, they didn’t want to pay for the synch license to use the master. Or at least that’s all I can think of. I don’t know why else they wouldn’t use the master. It was a money reason. Why would they hire some guys to just go into the studio and play our version of “Susie Q?” It doesn’t make any sense to me.

PHAWKER: A lot of bad financial shit went down around you guys, huh?

STU COOK: Oh yeah, we were often on the wrong end of the financial deals for sure.

PHAWKER: I briefly want to touch on the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 1993. By that point, you guys had become estranged, there were more lawsuits etc. and Fogerty refuses to perform with you guys when you were being inducted. And he banned you from the stage and then went on to play Creedence songs with an all star band including Bruce Springsteen and Robbie Robertson.

STU COOK: He didn’t ban us, he just said he wouldn’t play if we were going to play. So, the Hall of Fame had to decide whether or not they wanted to induct Creedence with John playing or the other way around. It was not a great evening, to say the least. They kept telling us we were going to play for well over a month then we get there and find out we aren’t doing anything. So, that was a bit of a surprise.

PHAWKER: So, did you guys watch the performance from the audience.

STU COOK: No, we got up and left.

PHAWKER: That would be the dignified thing to do.

STU COOK: We split and we went to the bar.

PHAWKER: Is it true that Tom Fogerty’s widow even brought his ashes along to the ceremony?

STU COOK: You know, that’s a good legend, it may be true. I don’t know. I’ve never spoken with her about it. Yeah, she might have done that. It was a big evening for Tom even if he wasn’t there in the flesh to receive the honor. I think John just sort of pissed all over the band that night. I think he ended up looking like more the jerk than us.

PHAWKER: So 2017, where do things stand. Are you guys still not on speaking terms or is there still a lot of animosity between each other?

STU COOK: Well, we sued John in 2014 over trademark infringement and he countersued us for more money. Of course, money is more important to him than anything else I can think of. We settled our lawsuits in 2017. So, it’s still pretty fresh. There may be some good that could come out of this at the end of the day, there’s a clear path now for Creedence product and merchandise to be officially licensed and sold.  There will be an official Creedence Clearwater Revival website set up and we will take it from there. We laid out the groundwork for a solid business/working relationship. That’s not to say that we are friends, but we decided to stop fighting and try and preserve what’s left of the goodwill of the band and move on.

There will be an official Creedence Clearwater Revival website set up and we will take it from there. We laid out the groundwork for a solid business/working relationship. That’s not to say that we are friends, but we decided to stop fighting and try and preserve what’s left of the goodwill of the band and move on.

PHAWKER: If the stars align, could you see a situation where there would be a reunion of the remaining members?

STU COOK: I don’t know what stars you are talking about. It’s a very big universe, sir. At this point, I wouldn’t advise anyone to hold their breath, but you just never know what’s going to happen.

PHAWKER: How old are you?

STU COOK: I just recently turned 72.

PHAWKER: I must say, you sound like a much younger man on the phone.

STU COOK: Oh, well thank you. Three of us are 72.

PHAWKER: Well, you know I don’t mean to be morbid but the clock is ticking.

STU COOK: Yeah, there’s way more sand in the bottom of the glass than there is in the top of the glass.

PHAWKER: Well, I wouldn’t wait much longer to have a reunion. So, just a couple questions about Creedence Clearwater Revisited [pictured, right]. Who’s doing vocals, you?

STU COOK: No, we have a young man named Dan McGuinness as the lead singer.

PHAWKER: And you’re doing the whole song book?

STU COOK: Pretty much, yeah. This is our twenty-second year.

PHAWKER: You guys have been doing it for 22 years? And Creedence was about four years, right?

STU COOK: Creedence was about three-and-a -half, we were together about nine years before Creedence.

PHAWKER: I wanted to ask you — this is fascinating to me — you produced The Evil One for Roky Erickson?

STU COOK: Yeah, I produced 15 tracks for Roky in the late 70s early 80s.

PHAWKER: So, how did that come about?

STU COOK: I was friends with a guy who became Roky’s manager and then he asked me if I would produce and I said, well I’ve always been a big Roky fan”.

PHAWKER: The 13th Floor Elevators moved to San Francisco for a time. Did you see ever them play?

STU COOK: I never saw them play, but I’ve seen the posters. I was pretty regular at the Avalon Ballroom and at the Fillmore when I was going to college. So, anyway I welcomed the opportunity to work with Roky. I worked with his band and did a lot on the arrangements and the production. I worked with Roky a lot.

PHAWKER: What kind of shape was he in at the time?

STU COOK: He was pretty good, pretty normal. I remember one session I had to go get him out of the mental institution in Austin, Texas just so I could take him recording.

PHAWKER: And is that who you recorded with in Austin? Roky was an inmate at the Rusk State Mental Hospital in Austin.

PHAWKER: He was still serving his time at Rusk from the pot bust?

STU COOK: One of the pot busts.

PHAWKER: Wow, and they let him out to record?

STU COOK: Yeah, I had to go check him out, it was crazy. I would put on a tie and go down there and act like I was going to be a responsible custodian of Mr. Roger Kynard Erickson for the day. And the funny part is that all of the other patients would come up to me, they thought I was a doctor because I had a tie on. They were trying to get me to get them out too.

PHAWKER: Oh, man. What was your impression of Rusk. Was that a creepy depressing place?

STU COOK: Yeah, it was an old school mental hospital. Nothing but bare walls and minimal furniture. People standing in corners talking to walls. It was old school warehousing of people with mental problems. It didn’t seem to me that the disturbed people were even kept away from the dangerous people. They just put them all in a big room like an oversized classroom and just rounded them up for meals and so on. It was pretty loose. But I was able to get him out and take him to the studio which was owned by the guy who wrote “Muskrat Love.” His name was Willis Alan Ramsey. He owned the studio. Hound Sound it was called and we did the vocals there and I would buy Roky dinner and take him back at night. He was eventually released and toured with the band. We recorded 15 songs. The first one was called TEO and that was released on CVS UK and then 415 Records in San Francisco picked up an option to do another album and they called that one The Evil One. So, we used five new songs and five other songs for that album but there’s a total of 15 recorded. I think I played bass on a couple of tracks.

PHAWKER: Do you think that all of the monster imagery was the result of him watching a lot of horror movies or did that reflect something internal that was going on?

STU COOK: A little bit of both, honestly. He was definitely living in both worlds at the time, but he has a memory like a steel trap. He knew some of these movies, during what would normally be called instrumental, he quoted lines from films. I’m surprised we didn’t get a notice from their lawyers. Roky had humor and sometimes you could tell he would get down, but a lot of times he was just playing it for all it was worth. Because he learned by being in the big house how to work people.

PHAWKER: Acting crazier than he was?

STU COOK: Yeah. He went there for pot, he wasn’t really crazy. He just avoided a long jail term in Texas, but I’ve seen this happen to other people, you kind of grow into it. If you’re trying to play the role of being crazy, pretty soon you get what you wish.

PHAWKER: I’m sure you lose your bearings too if you have no baseline of sanity to model your behavior on and everyone else is crazy all the time.

STU COOK: I think that’s what happens, you just become more like your surroundings. It’s a survival skill and you learn how to work it for an extra pack of cigs or whatever’s going on. That was one of his problems, all of his friends couldn’t stop giving him drugs. That didn’t help much.

PHAWKER: Talk about a drug war martyr. It’s hard to believe Roky had to serve 10 years in a Texas hospital for the criminally insane for a couple joints.

STU COOK: It’s about to start again, man. The Attorney General wants to go for medical marijuana dispensaries. Not my idea of a classy guy. My favorite quote by Jeff Sessions is, “I used to like the Klan until I found out they smoked marijuana.”

PHAWKER: The quote is, “I used to think the Klu Klux Klan were okay guys…“

STU COOK: Until he found out they smoked weed. There you go, good people don’t smoke marijuana.

CREEDENCE CLEARWATER REVISITED @ SUGARHOUSE CASINO JUNE 30TH 9PM