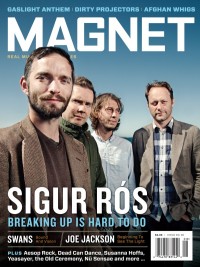

EDITOR’S NOTE: In advance of Sigur Ros’ show at the Mann Center on Friday, we present this encore edition of my 2012 MAGNET cover story.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Iceland isn’t the end of the world but you can see it from here. This is both a blessing and to a lesser degree a curse. Much less. It is the land that time forgot, and as such a place of uncommon purity. Primeval is the word that comes to mind: smoldering volcanoes, black sand beaches, towering geysers, geothermal hot springs, epic waterfalls, vast lava fields that recede infinitely out to the horizon, bumping up against glaciers thousands of years old. Elves. Not for nothing did Ridley Scott select the hinterlands of Iceland to film the stunning, panoramic ‘beginning of time’ segments in Prometheus, his recently-released sorta-prequel to Alien. The Viking ‘sagas’, the epic poems situated in pre-historic Iceland, are said to have been a primary inspiration of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Iceland isn’t the end of the world but you can see it from here. This is both a blessing and to a lesser degree a curse. Much less. It is the land that time forgot, and as such a place of uncommon purity. Primeval is the word that comes to mind: smoldering volcanoes, black sand beaches, towering geysers, geothermal hot springs, epic waterfalls, vast lava fields that recede infinitely out to the horizon, bumping up against glaciers thousands of years old. Elves. Not for nothing did Ridley Scott select the hinterlands of Iceland to film the stunning, panoramic ‘beginning of time’ segments in Prometheus, his recently-released sorta-prequel to Alien. The Viking ‘sagas’, the epic poems situated in pre-historic Iceland, are said to have been a primary inspiration of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth.

The occasion of my visit to this magical Nordic isle is the release of Valtari, the first proper studio  album by Sigur Ros since since 2008’s nudist-friendly Með suð í eyrum við spilum endalaust, which marks the cessation of a so-called ‘indefinite hiatus’ that many feared signaled the end of the band after seven albums in 18 years. Sigur Ros, which in English means ‘victory rose,’ first showed up on most people’s radar a dozen years ago with the release of Ágætis byrjun, a grand bargain of ethereal post-rock, minimalist psychedelia, and sweeping orchestral maneuvers, guided, like a beacon in the fog, by the mesmerizing otherworldly voicings of their singer, Jón Þór Birgisson, aka Jonsi. It sounded like somebody snuck a tape recorder into heaven. Like cherubim swinging the hammer of the gods. It was said the singer was in fact singing in a newly invented language of his own device. The name of this language in Icelandic was Volenska. In English it was called Hopelandic.

album by Sigur Ros since since 2008’s nudist-friendly Með suð í eyrum við spilum endalaust, which marks the cessation of a so-called ‘indefinite hiatus’ that many feared signaled the end of the band after seven albums in 18 years. Sigur Ros, which in English means ‘victory rose,’ first showed up on most people’s radar a dozen years ago with the release of Ágætis byrjun, a grand bargain of ethereal post-rock, minimalist psychedelia, and sweeping orchestral maneuvers, guided, like a beacon in the fog, by the mesmerizing otherworldly voicings of their singer, Jón Þór Birgisson, aka Jonsi. It sounded like somebody snuck a tape recorder into heaven. Like cherubim swinging the hammer of the gods. It was said the singer was in fact singing in a newly invented language of his own device. The name of this language in Icelandic was Volenska. In English it was called Hopelandic.

But as of late there were signs trouble in paradise. Allegedly insider reports surfaced intermittently on the Internet indicating that the new album had been made and scrapped at least three times. Then, shortly after Valtari was released in May, word came from the Sigur Ros camp that Kjartan Sveinsson, the band’s multi-instrumentalist (piano, keyboards, organ, flute, tin whistle, oboe, banjo, guitar) — the one member of the band who can read music, the member of the band who wrote the signature string and horn parts — would not be joining the band on the planned year long tour in support of Valtari. His reason for not touring — that it would “not necessarily the most productive” use of his time — struck many as a curious thing for a man who makes his living as a musician. Could it be that hope no longer springs eternal in Hopelandia?

Magnet sent me to Iceland to find out. I was doing what I usually do between cover stories — lying around in a Saigon hotel room smoking and listening to The Doors in my underwear — when the order came down from on high. My instructions were cryptic: get on a plane from Philadelphia at the crack of dawn. Fly to Minneapolis and wait there for eight hours, then board a plane shortly before midnight and fly through the night, arriving on the shores of Iceland with the rising sun. There I was to be picked up by a very nice man with an unpronounceable name who would chauffeur me into the heart of Reykjavik, Iceland’s capital city, and await further instructions. As the plane approaches, dropping out of the Western sky at sunrise, looking out the window you would be forgiven for thinking you were landing on the moon. As far as the eye can see is the vast lunar wastes of blackened lava fields that recede into the horizon. The landscape is dotted with smoking holes in the ground. Nearly 99% of Iceland’s energy needs are provided by geothermal and hydro power. Keflavik International Airport is actually part of a de-commissioned NATO base that has since been converted into a university and a hospital.

My hotel is situated by the harbor, and there is a massive whaling ship dry-docked in front. I check in and crash. Hard. I am awakened at two in the afternoon by the urgent ringing of one John Best, Sigur Ros’ manager. Best is a tweedy Londoner with bushy mustache and eyeglasses left over from the Ford Administration. Even after spending a solid 48 hours with the man, I still can’t tell if his look is ironic  or hip beyond my comprehension. A gifted raconteur with an ear for what comes next, Best is a veteran of London’s Brit-Pop era, working as a publicist for Elastica and then managing The Verve, all the while dating the lead singer of Lush. He started working with Sigur Ros as their publicist but soon transitioned into manager, a position he has held since the release of Aegtis Byjrnum.

or hip beyond my comprehension. A gifted raconteur with an ear for what comes next, Best is a veteran of London’s Brit-Pop era, working as a publicist for Elastica and then managing The Verve, all the while dating the lead singer of Lush. He started working with Sigur Ros as their publicist but soon transitioned into manager, a position he has held since the release of Aegtis Byjrnum.

He fetches me at my hotel and we walk the streets of Reykjavik in search of Vegamont, the sidewalk cafe where I will meet the first of my interview subjects, Sigur Ros’ bassist Georg Holm, aka Goggy. It is an incurably sunny day in the low 70s, all blue skies and zero humidity. On a clear day in Iceland you can see forever. Literally. Out my hotel window I can see the snow-capped Snæfellsjökull volcano some 120 miles away as the crow flies.

Reyjavik is a charming, hilly spread of low-rise two-story chalk white buildings and narrow cobblestone streets where nearly a third of Iceland’s mere 319,000 citizens reside. By American standards, Reykjavik feels more like a historic village than a nation’s capital. In the wake of Bjork’s international stardom, Reykjavik has attracted the attention of bohemian jet-setters like Blur’s Damon Albarn who — Best points out as we pass it — owns a minority interest in one of the city’s hippest bars. Everything is immaculately clean. Everyone is blond and tan and stylish and seemingly 25. Nobody seems to have a job. It’s a Wednesday afternoon and the sidewalk cafes are filled to capacity with Icelanders hoisting frosty mugs of beer. And yet there are no discernible signs of poverty anywhere.

“That was the most shocking thing about going to America for the first time,” says Holm. “That some people could be so rich and everyone else could be so poor. It’s not like that here.”

Holm is the only member of Sigur Ros, and for that matter one of the few in Iceland itself, who doesn’t have a ‘pater name,’ a tradition stretching back to Iceland’s pre-history as a colony of first Norway then Denmark, but long-since abandoned in both countries, wherein a child’s last name is created by taking the first name of the father and attaching the suffix ‘dottir’ (daughter) or ‘sson’ (son) depending on gender. “We don’t really use surnames in Iceland. So people don’t call people, even formally, using their last name. Everyone calls everyone by their first name. So everyone would call me Georg, they wouldn’t call me Mr. Holm. It just doesn’t exist in Iceland.”

Holm is a ruggedly handsome 36-year-old blonde who who always uses his indoor voice even now as we sit outside in a noisy outdoor cafe. The sidewalk cafe is packed with handsome young Nordics tippling crisp pilsners and soaking up the summer sun. Iceland is situated just south of the Arctic Circle, so the sun never really sets this time of the year. It is a trade-off for the fact that come winter it will stay completely dark 24-7. “You get used to it, I really enjoy it actually,” says Holm. “I’m going to bed and it’s midnight and the sun is still shining and I wake up and the sun is still shining.” Despite its close proximity to the polar regions, Iceland’s climate is mild and temperate thanks to the warming vectors of the gulf stream’s North Atlantic Current. The build up of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere appears to have redoubled that effect. “We joke around that you can’t beat global warming because the weather in Iceland is so nice these days,” says Holm.

I ask him about the so-called ‘indefinite hiatus’ and reports that the band almost called it quits during the making of Valtari. “‘Indefinite hiatus’? That sounds serious,” says Holm. I agree it does sound serious. How serious was it? “That didn’t come from us, there was nothing like that,” he says. “After the tours for Med Sud, we had decided to take a year off. We weren’t going to work until the end of 2009 or the beginning of 2010. The idea was just to not be in a band for a year, but it just went on a little bit longer. There was definitely much more time off.” And what did he do with that time? “I don’t know, just family stuff, I guess, normal things,” he says. “Take the kids to school and…” The rest of his thought shattered by the sound of another balloon popping.

________

George Holm first met Jón Þór Birgisson, aka Jonsi, at the dawn of the 90s when both were enrolled in a  technical school neither were long for. Jonsi was miserable studying mechanical drawing and Holm would soon quit to attend film school. In 1994 they formed a three piece with drummer Ágúst Ævar Gunnarsson. They called them themselves Victory Rose, the English translation of Jonsi’s newly born sister’s name. Later they would switch to a variant of the Icelandic version, Sigurros. They spent about three years working on their little-heard, rarely-discussed debut, Von. What took so long, I wonder aloud? “Weeks and weeks on and off of hanging around the studio, which turned into months and months, a lot of time given over to things like trying to record the rain out the window, ordering a pizza and hanging around basically,” says Holm. The reverb-drenched album was indebted to early influences like Spiritualized and Smashing Pumpkins. The album barely registered outside of Iceland and even at home it attracted very little attention. Upon its release, Von sold a whopping 300 copies. “To be honest, I think they are rather embarrassed by it and would rather it never existed,” says Best.

technical school neither were long for. Jonsi was miserable studying mechanical drawing and Holm would soon quit to attend film school. In 1994 they formed a three piece with drummer Ágúst Ævar Gunnarsson. They called them themselves Victory Rose, the English translation of Jonsi’s newly born sister’s name. Later they would switch to a variant of the Icelandic version, Sigurros. They spent about three years working on their little-heard, rarely-discussed debut, Von. What took so long, I wonder aloud? “Weeks and weeks on and off of hanging around the studio, which turned into months and months, a lot of time given over to things like trying to record the rain out the window, ordering a pizza and hanging around basically,” says Holm. The reverb-drenched album was indebted to early influences like Spiritualized and Smashing Pumpkins. The album barely registered outside of Iceland and even at home it attracted very little attention. Upon its release, Von sold a whopping 300 copies. “To be honest, I think they are rather embarrassed by it and would rather it never existed,” says Best.

Then three things happened that would change everything. The first was Jonsi started singing in a falsetto having accidentally discovered that not only could he control his voice better, but it gave his voice much more power and reach. In time, Jonsi would fashion his voice into one of the most distinctive and original-sounding instruments in 21st Century rock music. The second was Holm was given a violin bow as a birthday present. He tried using it on his electric bass and it sounded…terrible. “I had no idea you needed to use rosin,” says Holm, who quickly cast the bow aside. Some time thereafter Jonsi picked up it up and, after jacking up his effects pedals, ran it across the strings of his guitar and…eureka! The Sigur Ros sound was born: spectral in texture, glacial in pacing, oceanic in scope, aspirational in intent, transcendental in effect. Armed with this new arsenal of otherworldly sounds, Sigur Ros commenced writing and recording Aegtis Byrjum, the album that would not only make them homeland heroes but a global cause celebre. Nobody had ever heard anything quite like it before or, for that matter, since. These songs would become, in the hearts and minds of devoted fans and smitten critics, the national anthems of Hopelandia.

“We had this accidental moment of kind of being cool and you would get all these glitterati types showing up backstage wanting to meet the band,” says Best. By ‘glitterati’ he means people like Tom Cruise and David Bowie and Courtney Love. Brad Pitt was an early fan, telling interviewers they were his favorite band. Lars Ulrich sent them a thank you note after seeing them in San Francisco. Sigur Ros served as the soothing soundtrack to the birth of Apple Martin, the child of Coldplay’s Chris Martin and actress Gywneth Paltrow. Gillian Anderson, aka Agent Moulder form the X-Files actually followed the band on tour for a time. Even Motley Crue’s Tommy Lee was a fan, writing in his biography that he liked to listen Sigur Ros in the fetal position.

“And they all kind of went away about five or six years ago, I guess,” says Best, wistfully.

Holm shrugs as if to say Sigur Ros is, in the grand scheme of things, none the poorer for their absence. They were Sigur Ros before the celebrities took notice and they will continue to be Sigur Ros long after they’ve moved on to the next flavor of the moment. Amen to that.

______________

At this point Jonsi happens by our table on his way home from the hardware store. He is tall and lean and dressed in a red jersey and black peg-legged track suit pants that resemble jodphurs. He still has his trademark coiffure that one wag aptly described as “a cockatoo frond of sticky-up hair.” Blind in his right eye since birth, Jonsi always seems to be staring off into the middle distance, entranced by the spectacle of something invisible to the rest of us. “Weirdly, he has no problems with depth perception his brain just works it out,” says Best. “If I close my right eye, I can’t work out where anything is; I’d be knocking things over on the table. You can play table tennis with Jonsi, and he will beat you. You try and play tennis with one eye closed I guarantee you you can’t. I have no idea how he does it.” We bid Holm adieu and tag along with Jonsi for a walk-and-talk. We are quickly lured into a neighboring bar by the blaring sounds of the “Rocky” theme. Both Jonsi and Best are immensely amused by this fact given that I live in  Philadelphia. Inside we find the surreal scene of a man well into his 70s striking muscle man poses while a phalanx of photographers snap away. It turns out he is the owner of the Reykjavik-based Brio brewery that is celebrating it’s two-year anniversary. There is a thriving beer culture in Iceland, despite the fact that beer was officially banned from 1915 to 1989. Nobody here seems to think that’s remotely weird, nor do they seem to think it odd that up until 1985 TV stations were legally prohibited from broadcasting on Thursdays, presumably in the hope that people would read a book or go outdoors or have a conversation.

Philadelphia. Inside we find the surreal scene of a man well into his 70s striking muscle man poses while a phalanx of photographers snap away. It turns out he is the owner of the Reykjavik-based Brio brewery that is celebrating it’s two-year anniversary. There is a thriving beer culture in Iceland, despite the fact that beer was officially banned from 1915 to 1989. Nobody here seems to think that’s remotely weird, nor do they seem to think it odd that up until 1985 TV stations were legally prohibited from broadcasting on Thursdays, presumably in the hope that people would read a book or go outdoors or have a conversation.

As we walk, Best brings Jonsi up to speed on some of the latest developments in the business side of thing: Dub step DJ Flux Pavilion (25 million plays on YouTube!) wants to do a re-mix, Save The Children wants them to play a benefit concert literally up a tree (don’t ask) and Sigur Ros has been invited to perform at the upcoming 67th birthday party for Burmese democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi, who just completed 10 years of house arrest, being held in Dublin, where she will receive Amnesty International’s highest honor, the Ambassador of Conscience Award, from Bono. Regrettably it is an invite that will have to be declined. Sigur Ros is in no shape to deliver a live performance right now. For the last few weeks the band has been locked away in their rehearsal space trying to re-configure themselves as a live band in the wake of multi-instrumentalist Kjartan’s decision not to tour this time around. It will take three people to replace him: Ólafur Björn Ólafsson of Stórsveit Nix Noltes and Benni Hemm Hemm will replace him on keyboard and oboe, and Hólm’s younger brother Kjartan Dagur Hólm (from the band For a Minor Reflection) will play guitar in his place. Time is running out, their world tour begins in a matter of weeks

Eventually we wind up back at Jonsi’s residence, a gorgeous low-slung, tastefully-appointed two story carriage house made of black lava rock. Built back to 1882, Jonsi’s home is one of the oldest residential structures in Reykjavik. Jonsi lives here with his longtime partner Alex Somers, an American musician and producer who mixed and arranged Valtari. His sisters lilja and inga birgisdóttir, who design and create Sigur Ros’s album covers, band photos and merchandise live across the street. We head outside to inspect a series of cracks that have emerged in the side of the house and must be patched to stop rainwater from getting in and undermining the foundation. Jonsi is only half kidding when he tells me that he will grant me an interview if I help him patch the wall tomorrow. Deal, I say, warning him that I am terrible at this kind of Mr. Fixit stuff. We stroll over to a nearby restaurant for a meal and afterwards, if the stars align, an interview with the somewhat press-shy Sigur Ros frontman. The singer can be a little fickle and at this point in his career, Jonsi doesn’t have to do what Jonsi doesn’t want to do.

As we settle into a table, Best mentions that back in 2008 the band was approached by the Obama campaign which wanted to use the inspirational “Hoppipolla,” from 2005’s Taak, as their official campaign song. Although the band readily agreed to let them use it for free, the move was blocked by the suits at Universal Music who expressed concern about appearing partisan. This prompts Jonsi to ask about the status of the presidential campaigns in America. He finds it genuinely perplexing it could even be a close race. “Why would America not re-elect Obama?” he says. “He is so cool.” I try to explain how divided the country is and the ugly role that race plays in all of this. The mood lightens, however, when I school Jonsi about the exact nature of Rick Santorum’s Google problem. “That is so cool,” he says, laughing. As dinner wraps up, Jonsi decides he doesn’t feel like being interviewed today and excuses himself from the table.

Best shrugs apologetically. No matter, Best is actually a far more colorful and articulate narrator of Sigur Ros lore than anyone in the band. Talk turns to the impending tour. Best tells me that the band enlisted the services of innovative stage designer Willie Williams, who, in addition to his work with the Rolling Stones, REM and George Michael, has designed every U-2 stage set dating back to War, including the massive H.R. Giger-esque crab-shaped stage for the recent 360 Tour. This inevitably leads to talk of Kjartan’s decision not to tour. “Obviously it changes things, the dynamic of the band is three now,” says Best. “In many ways it’s an opportunity. Crisis is an opportunity. It has been a crisis, and it is an opportunity because Georg’s brother Kjartan who is the new piano player is a phenomenal musician. Plus he’s young and he’s Georg’s brother. So, that’s good, he will have his brother on the road with him. Now there will be five people on the stage, instead of four, so we have more hands to do more stuff, to create more of a wall of sound. Plus we’ll have strings and brass with us. Sigur Ros live is like a juggernaut. The can really fucking blow your hair back.”

__________

The next morning I meet-up with Sigur Ros drummer Orri Páll Dýrason at Kaffismidjan, his favorite coffee shop. It’s a charming little ramshackle bohemian affair, with thrift store furniture and an old record player and a stack of vintage vinyl serving jukebox duties. Orri pulls up on his new motorcycle, a Yamaha Diversion F, dressed head to toe in black. It is a badass look for somebody so soft-spoken. We sit out on a bench out front, bathing in the brilliant sunshine as we sip coffees and nibble whole grain toast and jam. Orri is 35, married with children, tall and lean and topped off with a thatch of hair the color of straw and currently styled like John Lennon circa the White Album. Orri joined the band after Ágætis byrjun was recorded when charter drummer Ágúst Ævar Gunnarsson quit to go back to school. Orri is a man of few words. Very few. Starting a conversation with him is like trying to start a fire in the rain. There is a spark and then…nothing. I ask him about what music he likes to listen to these days. “I never listened much to music,” he says, hushed and haltingly. “When I was 13 is when I really listened to music, now I just listen to  whatever’s on the radio in the car.” I ask him about Kjartan’s decision not to tour. “There’s not much to talk about, it just is,” he says.

whatever’s on the radio in the car.” I ask him about Kjartan’s decision not to tour. “There’s not much to talk about, it just is,” he says.

With talk about music and the band going nowhere fast, I ask him about the elves, the so-called Huldufolk or hidden people, an ancient folk tradition that has a somewhat surprising currency in 21st century Iceland.

MAGNET: What can you tell me about this about the elf thing? You have to ask them permission to build roads or move houses?

ORRI: That’s exactly right. There are stories about that about when trying to move some pillars of rock to make a road and equipment just breaks down and stuff and then they have to get the elf specialist who can talk to elves.

MAGNET: There are elf specialists?

ORRI: Yeah. People who can see elves and talk to them.

MAGNET: Are they in the phonebook? You can call them up and say ‘I need an elf specialist’?

ORRI: I don’t know. Just someone who knows someone. I guess it’s like that.

MAGNET: How to you become an elf specialist?

ORRI: You have to be like clairvoyant.

With that he gets back on his motorcycle and, presumably by way of a farewell, says, “Have a nice lunch.”

“Yeah, we’re still trying to figure him out,” says Best when he comes by to collect me afterwards. We head down the road en route to the Apple Store where we are to rendezvous with Kjartan. But along the way we encounter a scene straight out of a Fellini movie: A small parade of pre-schoolers in yellow vests and paper crowns singing “The Lion Sleeps Tonight.” A policeman on a motorcycle provides escort. Apparently there is a rival parade of pre-schoolers from across town headed this way. They will meet somewhere in the middle of Reykjavik and have some sort of a sing-off. Also taking in this surreal scene, coincidentally enough, is filmmaker August Jacobsson who made the mind-blowing video for Sigur Ros’ “Svefn-g-englar” which features the members the Reykjavik’s Perlan Theater Group dressed like angels while swooning and swanning about on a mossy plain in slow motion and over-saturated colors. All the members of the Perlan Theater Group have Downs Syndrome or a similar mental disability. Somehow the video manages to sidestep even the whiff of exploitation, because what comes across to the viewer, in the end, is not their damage but rather their humanity.

____________

“Just like you had in Greece, people who didn’t have any assets but got really ‘rich’ by just getting loans and that’s exactly what happened here in Iceland,” says Sigur Ros multi-instrumentalist Kjartan Sveinsson, a raw-boned man with piercing eyes and a thick beard who looks like he stepped out of the pages of a 19th Century Russian novel. “It was so easy to get money. Money was so cheap from 2000 to 2008 and so everybody had a lot of cash and everyone was buying computers and plasmas TVs and big jeeps and all this shit that they don’t need. And those are the people who are really fucked today. People spending money that they didn’t have. I don’t know, I mean it’s really hard to kind of put a finger on what exactly is going on or what are the consequences.” We are sitting at yet another outdoor cafe in the village of Mosfellsbær, about 10 minutes drive from downtown Reyjavik. Behind him, carved into the side of large grassy knoll, is a silent testament to the excesses that led to Iceland financial meltdown in 2008: A series of roads that were never finished leading to houses that were never built. Across the way is Sundlaugin Studios, the former indoor swimming pool that Sigur Ros purchased and converted into a studio where just about everything from the Brackets album on was recorded.

As of late, the band has decided that owning your own recording studio is more of a liability than an asset. When you have unlimited time to record an album, you wind up using it. As a result, completing each Sigur Ros album took longer and longer, culminating in the never-ending gestation of the new album, Valtari, which features some tracks that were recorded as far back as 2005. Recently, Kjartan bought out the other three band members’ stake in the studio and has taken steps to make it a commercially viable recording studio.

“The studio wasn’t getting the attention it needed and we were sitting on this property,” says Sveinsson. “All this equipment inside wasn’t really being used or taken care. It was always kind of a second home to us so there were always dirty socks in the basement and stuff because some of the boys lived there for periods of time. All of us did, actually. I kind of wanted to clean it up and make it more professional. I hated going there and seeing all our gear so disorganized.”

I ask him the question that everyone in Sigur Ros’ orbit is desperate to have answered once and for all: Are you slowly leaving Sigur Ros? “I don’t know,” he says, with a shrug. “Maybe. It hasn’t been decided yet.” Sveinsson has always kept busy with musical side projects, among them scoring films like Ramin Bahrani’s  2009 short film Plastic Bag and Neil Jordan’s 2009 film Ondine. He has worked extensively with the Icelandic string quartet Amiina, which includes his wife Maria Huld Markan Sigfúsdóttir on violin, and has served as Sigur Ros’ string section on numerous tours. Sveinsson made NPR’s 2011 list of “100 Composers Under 40.” He hints at numerous irons in the fire, none of which he is ready to talk about. If you had to do over again, is there anything you would have done differently? “I wouldn’t change anything,” he says. “I don’t believe in that. Anything that happens makes it worth your while. All things are good in that sense. We all make mistakes but I’ve done nothing I can regret.”

2009 short film Plastic Bag and Neil Jordan’s 2009 film Ondine. He has worked extensively with the Icelandic string quartet Amiina, which includes his wife Maria Huld Markan Sigfúsdóttir on violin, and has served as Sigur Ros’ string section on numerous tours. Sveinsson made NPR’s 2011 list of “100 Composers Under 40.” He hints at numerous irons in the fire, none of which he is ready to talk about. If you had to do over again, is there anything you would have done differently? “I wouldn’t change anything,” he says. “I don’t believe in that. Anything that happens makes it worth your while. All things are good in that sense. We all make mistakes but I’ve done nothing I can regret.”

___________

When Sigur Ros started in 1994, back when they were still calling themselves Victory Rose, the Smashing Pumpkins was Jón Þór Birgisson’s favorite band. You can hear it in Sigur Ros’ debut Von, and for that matter you can hear in the core of their sound to this day: the grandeur, the melancholy and the infinite sadness. Back then Jonsi considered himself just a guitar player. Period. He hated the sound of his own voice and he only sang out of necessity, there was nobody else to do it and they didn’t want to be an instrumental band. Because they didn’t have a proper PA he had to plug his microphone into his guitar amp, which made it hard to hear himself over the sound of his guitar. Eventually he discovered that if he sang in falsetto his voice occupied a different place on the sound spectrum than his guitar and he could hear himself. He also realized he could control the pitch of his voice better and if he slapped some reverb on there, well, we just might have something. It was about this time he started using Holm’s discarded violin bow on his guitar which made him totally re-think the way he played guitar. “Less rock and roll riffs more droney, float-y, big sounds,” says Birgisson as we quaff crisp Icelandic pilsners at yet another sidewalk cafe. “Lots of reverbs and echoes and stuff like that. In the studio we recorded anything that we could record just to try and put it through effects machines and we found one I remember like a reverb effect we found was called ‘Nuclear’ that was longest we could find. So we used that on everything.”

Eventually they figured out that a little reverb goes a long way. Sigur Ros rarely played out in public, but they did rehearse and record all the time. One day the bowed guitar, the falsetto and Kjartan’s string and horn arrangements, not to mention hours and hours of elbow grease and sweat equity, came together in perfect storm of densely ambient, breathtakingly panoramic rock music. They played a finished track for a friend who nodded and called it “a good start.” That struck the band add a fitting album title, especially when translated into Icelandic: Ágætis byrjun. “We kind of knew we had something good going, you know,” says Birgisson. “Maybe it sounds cocky but we knew it was good.” It would take some time to unfold, but over the course of three years of touring, Ágætis byrjun would sell a million copies and make them international pop stars. Some culture shock was inevitable. “I really like touring in America now, but the first time I was a little skeptical,” says Birgisson. “You know it’s so easy to make fun of America. Especially going through customs, ‘Sir, stand behind the yellow line!’ Such an asshole. But you know, we love it now.”

One thing that Birgisson wants to clear up is that the whole Hopelandic thing is the fabrication of an overambitious music journalist. ” It’s just not true at all, there is no made up language at all,” he says. “When you write a song and you are a singer, you make vocal sounds that fit the line. There was one song on the first album with some made up stuff and some journalist ran with it and called it HOPELANDIC and that stuck.” Mostly people are mistaking Icelandic, the language Birgisson sings in 99% of the time, for Hopelandic.

Given that Iceland’s current Prime Minister, Jóhanna Sigurðardótti, is the first openly gay world leader, I ask him if coming out in Iceland was a traumatic experience. “It was no big deal what so ever,” he says. “I came out when I was 21, I grew up in the country side and didn’t know anybody that was gay, not one person. I was always different, I knew I was different in my head. I came out slowly. First I came out to my  friends, like really slowly. Then I told my parents, they had no clue. I was always very boyish, no female tendencies or being flamboyant or whatever. It was super easy. Not traumatic at all.”

friends, like really slowly. Then I told my parents, they had no clue. I was always very boyish, no female tendencies or being flamboyant or whatever. It was super easy. Not traumatic at all.”

Finally, I ask him the question I have traveled 2,687 miles and 14 sidewalk cafes to ask him: is this the end of the beginning or the beginning of the end? “I think Kjartan is slowly leaving the band,” says Birgisson. “It’s Iceland, things happen really slow. We never speak, we never talk to each other. It’s a funny group of guys, four very different guys, we’ve know each other many years, we have become very good friends but we don’t have many heart to heart conversations. We tour all the time, you learn to give each other a lot of space, and then when we come home we don’t hang out that much because you want to give each lots of space, enjoy your time off, stuff like that. I think Kjartan wants to expand more. He’s been playing with the band 16 years, I don’t know if he’s fulfilled, he wants to try something new, try something different.”

Did you two have a conversation about it?

“Kind of, but we were both really, really drunk and don’t remember much about it. Classic Sigur Ros style. But if or when he does leave, we would probably go back to being a trio like we were when we started out. I’m not done. We’re going on tour, I’m excited about it. Festivals. Beer. Can’t beat it.”