NEW YORKER: Only one Administration is known to have considered using the Twenty-fifth Amendment to remove a President. In 1987, at the age of seventy-six, Ronald Reagan was showing the strain of the Iran-Contra scandal. Aides observed that he was increasingly inattentive and inept. Howard H. Baker, Jr., a former senator who became Reagan’s chief of staff in February, 1987, found the White House in disarray. “He seemed to be despondent but not depressed,” Baker said later, of the President.

Baker assigned an aide named Jim Cannon to interview White House officials about the Administration’s dysfunction, and Cannon learned that Reagan was not reading even short documents. “They said he wouldn’t come over to work—all he wanted to do was watch movies and television at the residence,” Cannon recalled, in “Landslide,” a 1988 account of Reagan’s second term, by Jane Mayer and Doyle McManus. One night, Baker summoned a small group of aides to his home. One of them, Thomas Griscom, told me recently that Cannon, who died in 2011, “floats this idea that maybe we’d invoke the Constitution.” Baker was skeptical, but, the next day, he proposed a diagnostic process of sorts: they would observe the President’s behavior at lunch.

In the event, Reagan was funny and alert, and Baker considered the debate closed. “We finish the lunch and Senator Baker says, ‘You know, boys, I think we’ve all seen this President is fully capable of doing the job,’ ” Griscom said. They never raised the issue again. In 1993, four years after leaving office, Reagan received a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s. His White House physicians said that they saw no symptoms during his Presidency. In 2015, researchers at Arizona State University published a study in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, in which they examined transcripts of news conferences in the course of Reagan’s Presidency and discovered changes in his speech that are linked to the onset of dementia. Reagan had taken to repeating words and using “thing” in the place of specific nouns, but they could not prove that, while he was in office, his judgment and decision-making were affected.

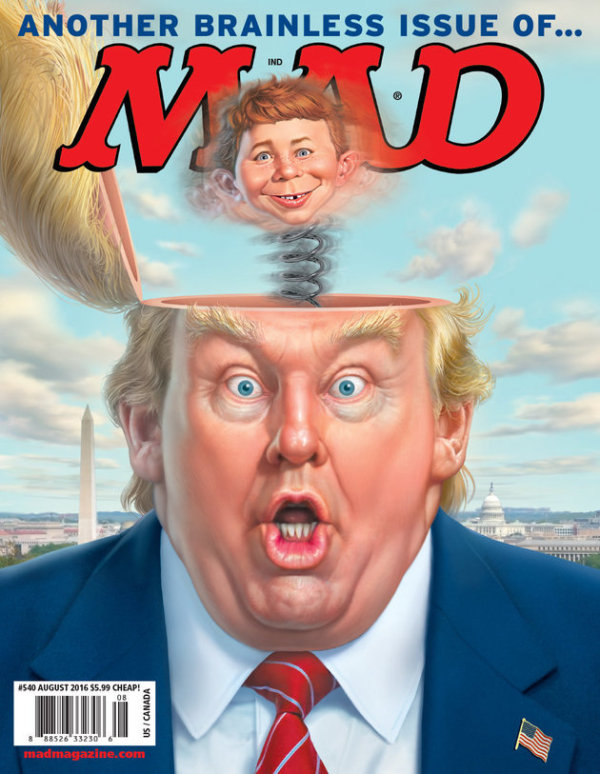

Mental-health professionals have largely kept out of politics since 1964, when the magazine Fact asked psychiatrists if they thought Barry Goldwater was psychologically fit to be President. More than a thousand said that he wasn’t, calling him “warped,” “impulsive,” and a “paranoid schizophrenic.” Goldwater sued for libel, successfully, and, in 1973, the American Psychiatric Association added to its code of ethics the so-called “Goldwater rule,” which forbade making a diagnosis without an in-person examination and without receiving permission to discuss the findings publicly. Professional associations for psychologists, social workers, and others followed suit. With regard to Trump, however, the rule has been broken repeatedly. More than fifty thousand mental-health professionals have signed a petition stating that Trump is “too seriously mentally ill to perform the duties of president and should be removed” under the Twenty-fifth Amendment.

Lance Dodes, a retired assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, believes that, in this instance, the Goldwater rule is outweighed by another ethical commitment: a “duty to warn” others when he assesses that a person might harm them. Dodes told me, “Trump is going to face challenges from people who are not going to bend to his will. If you have a President who takes it as a personal attack on him, which he does, and flies into a paranoid rage, that’s how you start a war.”

Like many of his colleagues, Dodes speculates that Trump fits the description of someone with malignant narcissism, which is characterized by grandiosity, a need for admiration, sadism, and a tendency toward unrealistic fantasies. On February 13th, in a letter to the Times, Dodes and thirty-four other mental-health professionals wrote, “We fear that too much is at stake to be silent any longer.” MORE