Artwork via THE NEW YORKER

THE NEW YORKER: Mercer is the co-C.E.O. of Renaissance Technologies, which is among the most profitable hedge funds in the country. A brilliant computer scientist, he helped transform the financial industry through the innovative use of trading algorithms. But he has never given an interview explaining his political views. Although Mercer has recently become an object of media speculation, Trevor Potter, the president of the Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan watchdog group, who formerly served as the chairman of the Federal Election Commission, said, “I have no idea what his political views are—they’re unknown, not just to the public but also to most people who’ve been active in politics for the past thirty years.” Potter, a Republican, sees Mercer as emblematic of a major shift in American politics that has occurred since 2010, when the Supreme Court made a controversial ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. That ruling, and several subsequent ones, removed virtually all limits on how much money corporations and nonprofit groups can spend on federal elections, and how much individuals can give to political-action committees. Since then, power has tilted away from the two main political parties and toward a tiny group of rich mega-donors.

Private money has long played a big role in American elections. When there were limits on how much a single donor could give, however, it was much harder for an individual to have a decisive impact. Now, Potter said, “a single billionaire can write an eight-figure check and put not just their thumb but their whole hand on the scale—and we often have no idea who they are.” He continued, “Suddenly, a random billionaire can change politics and public policy—to sweep everything else off the table—even if they don’t speak publicly, and even if there’s almost no public awareness of his or her views.” Through a spokesman, Mercer declined to discuss his role in launching Trump. People who know him say that he is painfully awkward socially, and rarely speaks. “He can barely look you in the eye when he talks,” an acquaintance said. “It’s probably helpful to be highly introverted when getting lost in code, but in politics you have to talk to people, in order to find out how the real world works.” In 2010, when the Wall Street Journal wrote about Mercer assuming a top role at Renaissance, he issued a terse statement: “I’m happy going through my life without saying anything to anybody.” According to the paper, he once told a colleague that he preferred the company of cats to humans.

Several people who have worked with Mercer believe that, despite his oddities, he has had surprising success in aligning the Republican Party, and consequently America, with his personal beliefs, and is now uniquely positioned to exert influence over the Trump Administration. In February, David Magerman, a senior employee at Renaissance, spoke out about what he regards as Mercer’s worrisome influence. Magerman, a Democrat who is a strong supporter of Jewish causes, took particular issue with Mercer’s empowerment of the alt-right, which has included anti-Semitic and white-supremacist voices. Magerman shared his concerns with Mercer, and the conversation escalated into an argument. Magerman told colleagues about it, and, according to an account in the Wall Street Journal, Mercer called Magerman and said, “I hear you’re going around saying I’m a white supremacist. That’s ridiculous.” Magerman insisted to Mercer that he hadn’t used those words, but added, “If what you’re doing is harming the country, then you have to stop.” After the Journal story appeared, Magerman, who has worked at Renaissance for twenty years, was suspended for thirty days. Undaunted, he published an op-ed in the Philadelphia Inquirer, accusing Mercer of “effectively buying shares in the candidate.” He warned, “Robert Mercer now owns a sizeable share of the United States Presidency.” MORE

FRESH AIR: According to our guest, Jane Mayer, one of the most influential figures in America today is a man most of us have never heard of. Mayer’s new piece in The New Yorker focuses on Robert Mercer, a wealthy hedge fund manager with very conservative – and as you’ll hear – somewhat eccentric views. Mayer writes that Mercer and his daughter Rebekah played critical roles in President Trump’s successful campaign last year, were influential in the transition to the White House and remain connected to key players in the West Wing. The Mercers have been major backers of Breitbart News and Steve Bannon’s other projects for years, and they were influential in getting Bannon and Kellyanne Conway into leadership positions in the Trump campaign. Jane Mayer is a staff writer for The New Yorker who’s won numerous honors including the George Polk Award. Her latest book now out in paperback is “Dark Money: The Hidden History Of The Billionaires Behind The Rise Of The Radical Right.” MORE

RELATED: The Blow It All Up Billionaires Are Destroying America

PREVIOUSLY: ZERO DARK THIRTY: A Q&A With The New Yorker’s Jane Mayer

________________

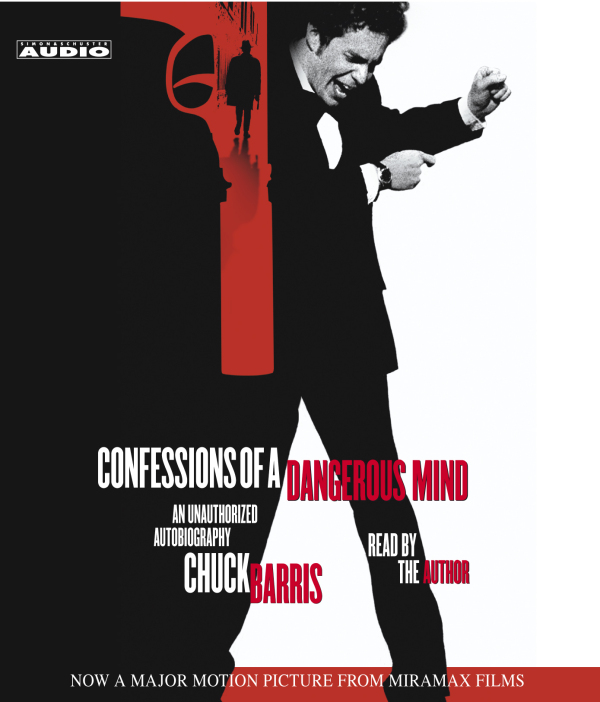

WASHINGTON POST: From his boundary-pushing game shows to his strange claims of being a CIA assassin, Chuck Barris lived large. The host of “The Gong Show” and the creative force behind “The Dating Game,” “The Newlywed Game” and many other game shows died of natural causes Tuesday at 87 in Palisades, N.Y., his publicist announced. Barris, who was born in Philadelphia, grew up in Bala Cynwyd, and went to Lower Merion High and Drexel Institute of Technology (now University), loaded ’60s and ’70s television with game shows, and later made waves when in an autobiography he claimed to be an assassin for the CIA, which the agency flatly denied. This book was adapted into a feature film “Confessions of a Dangerous Mind.” MORE

FRESH AIR: Chuck Barris, the creator of “The Dating Game,” “The Newlywed Game” and “The Gong Show” died yesterday at his home in Palisades, N.Y. He was 87. Barris called himself the king of daytime television. His critics called him the king of schlock. At one, point he was generating 27 hours of programming a week, mostly in daytime game shows. Barris invented a game show format that played on contestants’ personal relationships. Some of the laughs came from watching people publicly embarrass themselves as they revealed things about their private lives. “The Newlywed Game” had couples competing against each other. Husbands and wives were separated and asked questions about their marriages. “The Gong Show” was Barris’ intentionally tasteless answer to the talent show format, showcasing painfully bad performers. Barris sold his company in 1980, reportedly for $100 million. He later wrote an autobiography, “Confessions Of A Dangerous Mind,” in which he claimed to have been an CIA assassin, an assertion the CIA called absurd. That book was turned into a 2002 film directed by George Clooney. Here’s a clip from his first show, “The Dating Game,” which gave a young, single contestant the chance to cross-examine a panel of eligible bachelors or bachelorettes and choose one for a chaperoned date. MORE