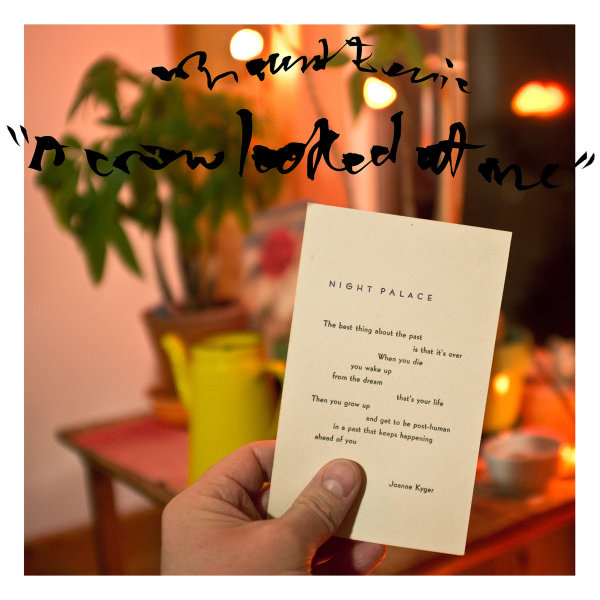

Death is real. It took Phil Elverum’s wife as he held her in his arms in the back bedroom of their home in Anacortes, Washington. French Canadian artist and musician, Geneviéve Castrée, died of pancreatic cancer on the morning of July 9, 2015, a year and a half after giving birth to her and Elverum’s daughter. The window open, Elverum shared the vibration of his love’s death rattle, and it enveloped him in the dissociative fog of trauma. Mount Eerie’s new album A Crow Looked At Me follows Elverum in the months after her death, as he waded through the minutia of everyday life. Much of Elverum’s music released as both The Microphones and Mount Eerie has confronted the inescapable fragility of life, and its place within the cyclical natural world. These themes are readily apparent in “The Moon” from The Microphones 2001 The Glow, Pt. 2, in which Elverum searches for closure, concluding, “Like the moon, my chest was full//Because we both know we’re just floating in the same space//Over molten rock, and we felt safe and discovered our skin is soft//There’s nothing left except certain death//And that was comforting at night out under the moon.”

Looking at lines like these after Geneviéve’s death, they assume a prophetic quality, as if the abyss that Elverum was always alluding to feeling within himself and observing in the natural world had been sending him indecipherable distress signals about Geneviéve’s tragedy to come. On track 3, “Ravens,” Elverum fleshes out his arcane connection with the natural world as he sings of sensing that two ravens he watched flying into the October sunset were an omen, “but of what I wasn’t sure.” He goes on, suggesting, “You were probably inside//You were probably aching, wanting not to die.” Elverum grounds the album with temporal roots, explicitly mentioning dates, “It’s August 12, 2016//You’ve been dead one month and three days.” When the album isn’t betraying the conventions of time and space, it shares Elverum’s paralyzing confrontations with the post-mortem mundane: throwing out Geneviéves toothbrush, closing the window in the room where she died, collecting the mail that continued to arrive for her after she’d gone.

Elverum’s idiosyncratic phrasing has never been as earnest or cutting as it is on A Crow Looked At Me. His voice, like a fusion of clarinet and french horn, speak-sings over sparse beds of music made up of succinct acoustic guitar strums, minimal drum machine, plush piano, and deliberate bass that trudges the way the listener imagines Elverum trudging through the world in the months he wrote these songs. Elverum’s music has always externalized the internal that he experienced within himself and observed in the natural world. The death of Geneviéve, though, erased the boundaries in Elverum’s world. In a statement he made about the album, he said: “The idea that I could have a self or personal preferences or songs eroded down into an absurd old idea leftover from a more self-indulgent time before I was a hospital-driver, a caregiver, a child-raiser, a griever. I am open now.” Make no mistake, A Crow Looked At Me is an exhausting album, but it transcends the normal boundary between musician and listener, offering a life-enriching experience that few albums can. It’s easy to distract ourselves with the burdensome truth of our own mortality. So natural to pretend like we will be the ones to finally escape death’s grasp. With its unreserved authenticity, A Crow Looked At Me tears away the blinders we put on to hide from the terrible reality of our vulnerability, pushing listeners to grab their loved ones while they’re here, because, fuck, death is real. – DILLON ALEXANDER