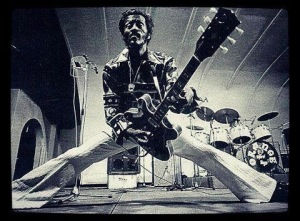

NEW YORKER: Berry, who died Saturday, at the age of ninety, was a proud and difficult man. He was also a genius. As a player, as a songwriter, and as a performer, he was a master of invention, transforming the rolling rhythms of Louis Jordan and the guitar figures of T-Bone Walker into the rhythmic foundation of half the rock songs you’ve ever heard. Rooted in the blues and with an ear for American country music, Berry blew things up and out with his first hits; he helped to create another form. Chuck Berry was to rock music what Louis Armstrong was to jazz—a foundational figure; if not quite singular, then as close as it gets.

“If you had tried to give rock and roll another name,” John Lennon once said, “you might call it ‘Chuck Berry.’ ”

Lennon—like Richards, like Bob Dylan, like the Beach Boys—was among the countless second-generation white musicians who understood the immensity of their debt to Chuck Berry. Their music would not have been possible without him. When the Beatles were playing in the clubs of Liverpool and Hamburg, much of their set was filled with Chuck Berry songs. To this day, it’s what any fledgling kid with a guitar wants to learn: “Little Queenie,” “Nadine,” “Jo Jo Gunne,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” “Brown Eyed Handsome Man.” He is in everyone’s ear. Berry inflects nearly all  of rock and roll. MORE

of rock and roll. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: In 1955, Mr. Berry ventured to Chicago and asked one of his idols, the bluesman Muddy Waters, about making records. Waters directed him to the label he recorded for, Chess Records, where one of the owners, Leonard Chess, heard potential in Mr. Berry’s song “Ida Red.” A variant of an old country song by the same name, “Ida Red” had a 2/4 backbeat with a hillbilly oompah, while Mr. Berry’s lyrics sketched a car chase, the narrator “motorvatin’” after an elusive girl. Mr. Chess renamed the song “Maybellene,” and in a long session on May 21, 1955, Mr. Chess and the bassist Willie Dixon got the band to punch up the rhythm.

“The big beat, cars and young love,” Mr. Chess outlined. “It was a trend, and we jumped on it.” The music was bright and clear, a hard-swinging amalgam of country and blues. More than 60 years later, it still sounds reckless and audacious. Mr. Berry articulated every word, with precise diction and no noticeable accent, leading some listeners and concert promoters, used to a different kind of rhythm-and-blues singer, to initially think that he was white. Teenagers didn’t care; they heard a rocker who was ready to take on the world.

The song was sent to the disc jockey Alan Freed. Mr. Freed and another man, Russ Fratto, were added to the credits as songwriters and got a share of the publishing royalties. Played regularly on Mr. Freed’s show and others, “Maybellene” reached No. 5 on the Billboard pop chart and was a No. 1 R&B hit. In Mr. Berry’s groundbreaking early songs, his guitar twangs his famous two-stringed lick. It also punches like a horn section and sasses back at his own voice. The drummer eagerly socks the backbeat, and the pianist — usually either Mr. Johnson or Lafayette Leake — hurls fistfuls of tinkling anarchy all around him. MORE