![]() BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Another year ticks by and 2016 reinforces the idea that the creation of serious, non-blockbuster films is less and less of interest in the American movie industry. No less a voice of authority than Martin Scorsese professed this opinion in a recent Associated Press article proclaiming “Cinema is Gone,” and while film culture is still consistently flourishing in pockets around the world, only four of the dozen films listed here as 2016 favorites are by U.S. directors, surely an all-time personal low.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Another year ticks by and 2016 reinforces the idea that the creation of serious, non-blockbuster films is less and less of interest in the American movie industry. No less a voice of authority than Martin Scorsese professed this opinion in a recent Associated Press article proclaiming “Cinema is Gone,” and while film culture is still consistently flourishing in pockets around the world, only four of the dozen films listed here as 2016 favorites are by U.S. directors, surely an all-time personal low.

People carry with them a lot of myths about creativity being a human constant but supportive economics are what is necessary for a sustained culture of music and art. While nearly all Hollywood’s resources go into franchise pictures and comic book adaptations, the support for small-budgeted films where skills are sharpened and experiments are played out has all about died. It was heartbreaking to listen to director Sean Baker on Bret Easton Ellis’ podcast discuss his experience as a filmmaker last year. He said despite having two highly-praised, nationally distributed films (2012’s Starlet and 2015’s Tangerine) the process left him so broke he had to move back with his parents. He and other indie directors have stated that despite the ubiquity of their work, they can’t find a way to make modern filmmaking anything other than an expensive hobby. This is not a scenario in which “golden eras” arise.

It’s popular to state that TV is what movies once were, the place where we gather and share stories. But while TV has loosened up its long-censorious standards (yet not so much that Scorsese was not slapped down by HBO over sex, drug-use and violence in his series Vinyl) its funding and format brings its own limitations. Working minute-to-minute to please advertisers, TV can’t help but a cast wide net in regards to subject matter, politics and actors chosen for roles. Extreme edges are sanded, music skews poppier, and actors are measured for likeability because success is based on viewers returning again and again. The filmmaking itself short-changes atmosphere and mood-setting asides and instead pushes forward with endless narrative. With films, your support is given upfront, with a filmmaker knowing he has his audience’s undivided attention through whatever he unveils, until the credits role. The finality of the non franchise-driven feature film form still makes for bolder statements then the open-ended structure of episodic TV.

Not that there isn’t TV programming to be enjoyed, I just wanted to give an explanation to why I’m hesitant to be peppering the list with the favorite TV moments that are seeping in to so many critic’s lists. It’s not only the form of film but the public theater-going experience I still cling to, still treasuring the experience of sitting with strangers while events unroll beyond our control on a screen taller than any of my walls at home. Looking at the list of films I’ve savored this year it is hard to buy into Scorsese’s “Cinema is Gone” proclamations, it’s just the film is less an American thing than ever. Maybe that’s not so bad, it wouldn’t hurt the national psyche any to be a little less U.S.-centric in our perspective, especially with films as strong as these making it to our shores.

____________

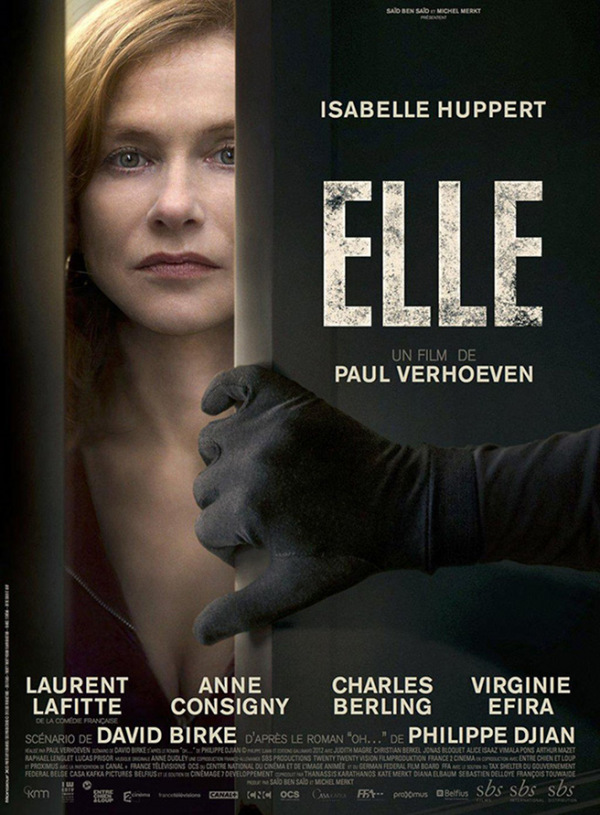

I think nothing shook me more than Isabelle Huppert’s performance in Paul Verhoeven’s Elle, a film that the director could not get financed in the U.S., or even find an English-speaking actress daring enough to take the leading role. Who is the figure in the black body stocking who rapes Huppert’s Michèle in the opening? And why doesn’t the experience send her to the police or at least slow down her sexually-voracious ways? There’s no end to the suspects, insecure men drawn to the ferociously intelligent woman, but the mystery of what compels Michèle’s actions is at the heart of the story, which has a Hitchcock-like ability to shock us at the psychological ramifications of its characters. At 78, Verhoeven still has that bad boyish audacity.

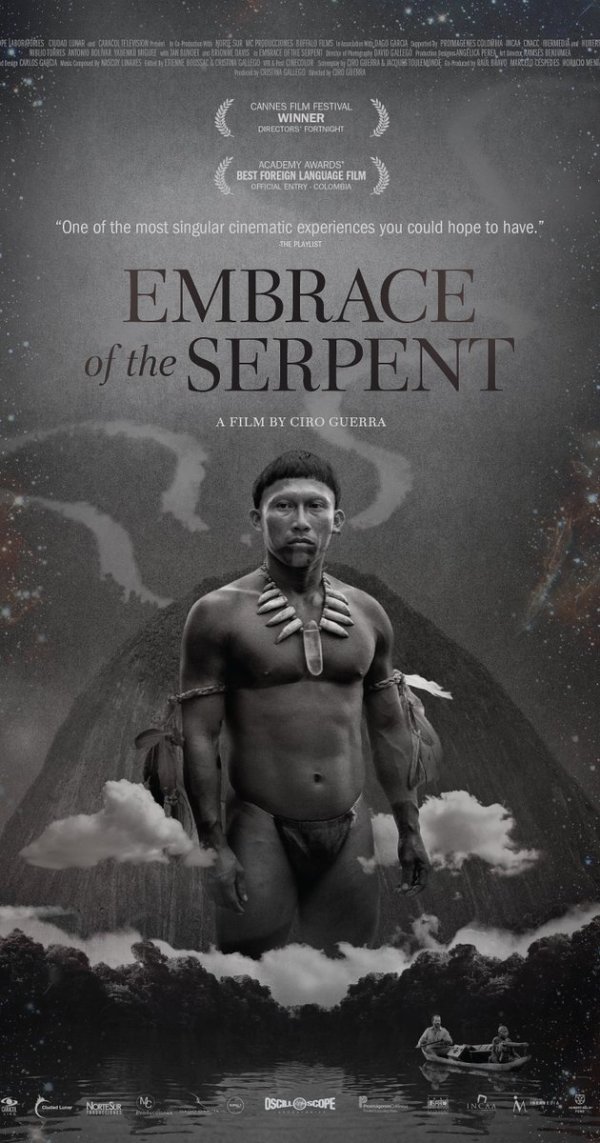

Columbian writer/director Ciro Guerra’s Embrace of the Serpent could get by on spectacle alone, so hypnotizing is the black and white imagery in this journey up the Amazon. Actually it is a pair of journeys, thirty years apart, each trying to solve a mystery that can only be answered by examining the land’s colonial past. The production itself stands as an awesome achievement but its the deeply-felt sorrow for the Amazonian people that gives the film its emotional heft.

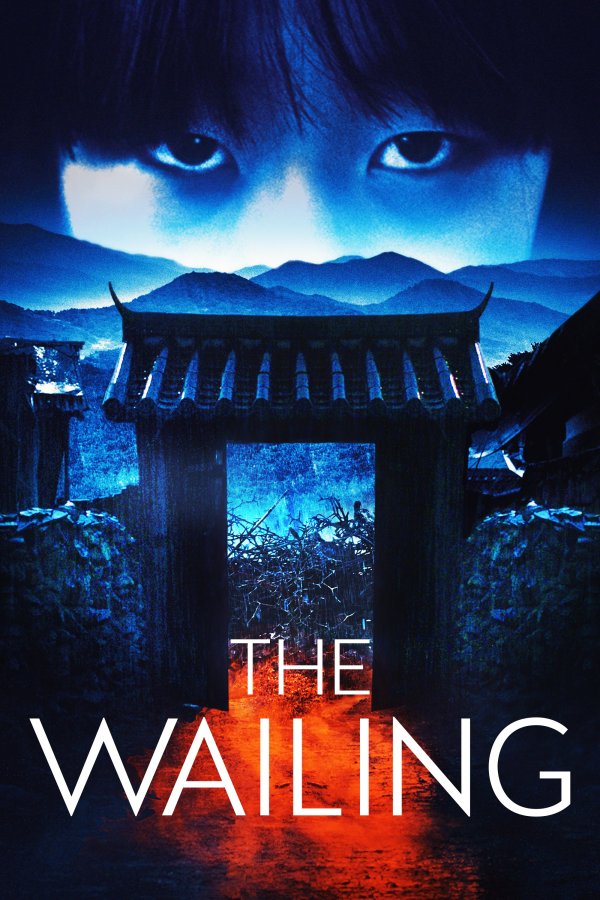

South Korean writer/director Na Hong-jin follows up two enthralling films (2008’s The Chaser and 2010’s The Yellow Sea) with his most ambitious yet, The Wailing. People are dropping dead in a rural community in South Korea, could the quiet Japanese man who moved to town be to blame? Kwak Do-won plays the slightly-bumbling policeman on the trail of a mystery that gets darker and more fantastic as it wears on. The film’s masterful mounting of detail suggest a world as fully-formed as a whole season of TV could but in a mere 156 minutes.

Greece’s Yorgos Lanthimos extends the absurdism of his 2009 breakthrough Dogtooth with The Lobster, a dark and whimsical satire about a world where single members of society must pair off or be turned into an animal of their choice. Just watching Ben Whishaw, John C. Reilly and Colin Farrell see this loopy premise through to the end would have been enough but Lanthimos switches settings half-way through to show us a bit of the world that gave birth to this system, as well as the wrong-headed rebels who fight hide in the woods and fight against it. A great example of a film that creates a fantastic world more thorough suggestion than special effects.

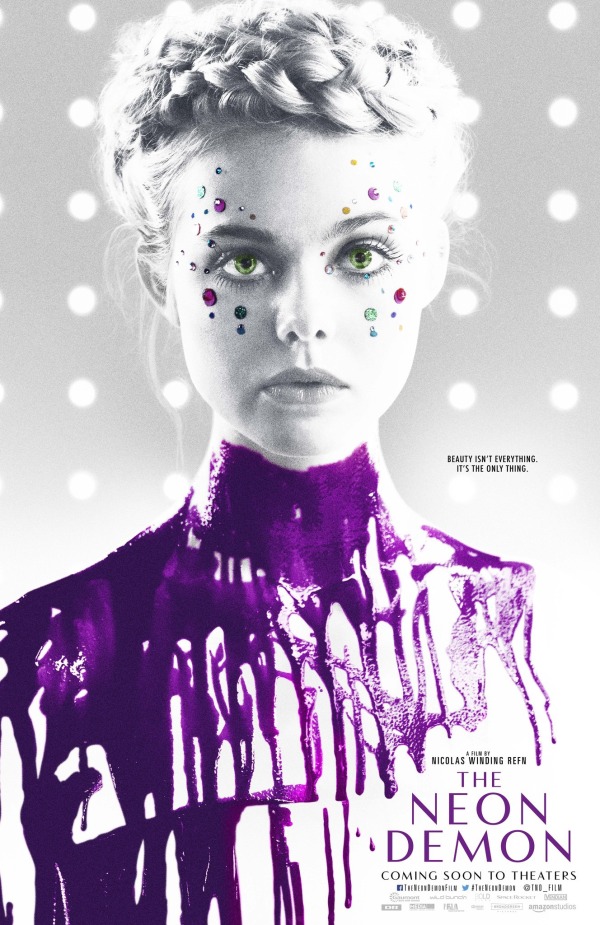

Neon Demon is similarly otherworldly, an endlessly stylized (with gorgeous cinematography by Natasha Braier) fable about a young women (a nervy performance by Elle Fanning) adrift in L.A. and entering the rarefied world of high fashion modeling. Directed by Nicholas Winding Refn, (of 2011’s Drive) Neon Demon ultimately makes its vampiric subtext explicit, a gambit that has split reviewers but the overall air of beautiful unease is what lingers.

I thought British director Andrea Arnold’s American Honey was going to be a breakout hit, unfortunately when I brought the film up, potential viewers would say, “Isn’t that the Shia LeBeouf film?” LeBoeuf sporting a rat’s tail might have repelled more people than it attracted but when I saw the film in the summer of 2016 It seemed to capture the somewhat blindly optimistic spirit among the youth supporting Bernie Sander’s Presidential campaign. The film is a very observational coming-of-age story of a young woman (newcomer Sasha Lane) as she sees the country with a couple van-loads of transient youth selling magazine subscriptions door-to-door. Arnold really captures both the intimacy and fast camaraderie that comes with self-created families as well as the possibility of darker fates.

Jeremy Saulnier’s Green Room was another immersive youth drama, one that only seems more spookily relevant with the rise of Trump America. A mixed-gender, casually liberal punk band gets caught broke on the road and agrees to a hastily booked gig in the wilds of Oregon. Once there they stumble into a backstage murder carried out by a backwoods white supremacist and the film becomes an claustrophobic seize thriller. Saulnier shows his previous 2013 hit Blue Ruin was no fluke in this brilliantly-mounted tale of terror with nicely-wrought performances from Alia Shawcat and the late Anton Yelchin.

Speaking of “brilliantly mounted” Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden arguably tops his line of ingeniously-crafted cinematic wonders. (which includes the modern classic Oldboy and 2014’s Snowpiercer.) It all sounds so gentile, a young thief infiltrate a noble house as a handmaiden to facilitate a daughter’s marriage to a fake count, but this quaint tale turns dark, morbid and surprising in ways that would be unexpected if you didn’t know Park’s twisted and violent work. Here he is at his most elegant though, which gives all those crazed plot turns an extra jolt. It’s the work of a stunning talent in mid-stride.

Love and Friendship really does deliver the sort of wit and pomp expected from such period pieces, letting writer/director Whit Stillman bounce back from his clunky 2011 comeback, Damsels in Distress. After dropping references to Jane Austen in his films for years, Stillman finally adapts a little-known Austen short novel into a vehicle that best captures his gift for well-turned dialogue and humorous intrigue. Red-headed Tom Bennett gives my favorite comic performance of the year as the stammering, foot in his mouth suitor, entering every conversation like a baby bull in a rhetorical china shop.

Old Stone unexpectedly slipped onto the list in mid-December. The debut of Canadian writer/director Johnny Ma who returned to the city of his birth, Shanghai, to film this bleak social drama. An excellent Chen Gang plays a cab driver who refuses to wait for the police to arrive and instead drives an injured pedestrian to the hospital. This act of decency bring the weight of society down on the poor man, with the law, the insurance companies and his family all cursing his life-saving act. The pressures shape the cab drivers character in surprising ways but it is the film’s final moments that make Old Stone brutally unforgettable.

I loved a pair of critical and popular favorites that have been dissected to death by now, Barry Jenkins Moonlight (I’d listed his debut, 2008’s Medicine For Melancholy as on of my favorites of the decade) although I’d agree with some of the film’s gay critics that the main character was made ridiculously chaste, making him much easier to embrace by mainstream audiences. Still, the film’s quiet observational style is too little seen in U.S. films, where plot points tend to be double-underlined for those slow on the uptake.

I was also was impressed by Kenneth Lonergan’s Manchester By the Sea, and not just for Casey Affleck’s doleful performance but for laying bare the falseness of so much sentimental cinema, where people’s lives are changed forever by one transcendent, clarifying moment. Casey’s depressive character is given a string of possibilities to hit that transformative, healing note but he can’t, because sometime emotional damage can’t be healed. As bleak as that reality is, having it stated so honesty in Lonergan’s film give it the power of truth, in an era when popular film seems more dazzled than ever by artful lies. Of course all cinema is an illusion but at its most profound when those artful lies are in service of some sort of arguable truth, and truth will be in need as much as ever in 2017. Here’s to the start of a new year at the movies…