Photo by AUTUMN DEWILDE

EDITOR’S NOTE: A considerably shorter version of this interview appeared in the November 10th edition of the Philadelphia Inquirer. Enjoy.

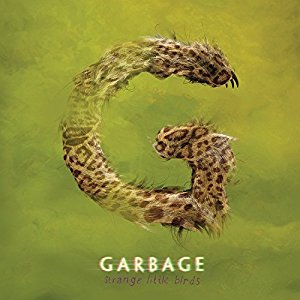

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR THE INQUIRER The Smart Studios Story documents the rise and fall of the legendary recording studio founded by acclaimed producer Butch Vig and his partner Steve Marker, where they recorded Smashing Pumpkins, Garbage, Death Cab For Cutie and, most importantly, Nirvana’s Nevermind. The film tracks the evolution of Smart Studios from its humble DIY beginnings as a glorified punk rock treehouse with free beer to the center of the alt-rock universe in the 90s only to close in 2010 as the age of the big, expensive analog studios gave way to digital home recording. In the interim, Vig has produced albums by the Foo Fighters, Goo Goo Dolls and Against Me! and reactivated Garbage, which went on hiatus in 2005. Recently, The Smart Studios Story has embarked on a screening tour around the country, which stopped in Philadelphia at PhilaMOCA earlier this month. In advance of the Philly screening, we spoke with Butch Vig from his home in Los Angeles where he was gearing up for a tour in support of Garbage’s surprisingly vital sixth album, Strange Little Birds.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR THE INQUIRER The Smart Studios Story documents the rise and fall of the legendary recording studio founded by acclaimed producer Butch Vig and his partner Steve Marker, where they recorded Smashing Pumpkins, Garbage, Death Cab For Cutie and, most importantly, Nirvana’s Nevermind. The film tracks the evolution of Smart Studios from its humble DIY beginnings as a glorified punk rock treehouse with free beer to the center of the alt-rock universe in the 90s only to close in 2010 as the age of the big, expensive analog studios gave way to digital home recording. In the interim, Vig has produced albums by the Foo Fighters, Goo Goo Dolls and Against Me! and reactivated Garbage, which went on hiatus in 2005. Recently, The Smart Studios Story has embarked on a screening tour around the country, which stopped in Philadelphia at PhilaMOCA earlier this month. In advance of the Philly screening, we spoke with Butch Vig from his home in Los Angeles where he was gearing up for a tour in support of Garbage’s surprisingly vital sixth album, Strange Little Birds.

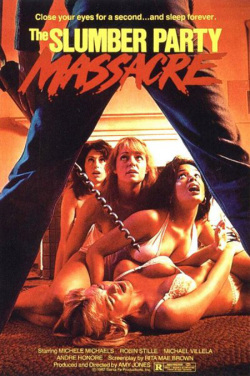

PHAWKER: One of your earliest musical endeavors was contributing a track to the  soundtrack of Hollywood slasher pic Slumber Party Massacre? Is this true? How did it happen?

soundtrack of Hollywood slasher pic Slumber Party Massacre? Is this true? How did it happen?

BUTCH VIG: That’s true. Long story short, I was in film school and a bunch of my fellow students moved out to Hollywood. One became David Lynch’s cinematographer, and another is Jerry Bruckheimer’s editor. Another friend from Wisconsin was working on Slumber Party Massacre. It’s just in the scene where somebody is walking down the beach with a boom-box and gets an axe in the back, but we were thrilled to be a part of it.

PHAWKER: Judging by the documentary, the Midwest indie-rock scene seemed more about D.I.Y. than adhering to some specific punk-rock orthodoxy. Is that true?

BUTCH VIG: Yeah it is. We were never elitist about any kind of music that we worked with or anything. One of the reasons we did so many hardcore punk bands is there was a thriving scene at the time. As soon as you get a couple bands coming into Smart they would just tell their friends. We never advertised and it was all word of mouth. Anyone who wanted to book time there could. It was good learning ground for me because I learned how to record everything, even though I didn’t really know what I was doing. You had to figure it out by the seat of your pants.

PHAWKER: Cheap beer seemed to have played a central role in these proceedings as it seemed to do with many aspects of life in the Midwest, can you speak to that a little bit?

BUTCH VIG: Growing up in Wisconsin that’s part of the M.O, that’s what people do. They go  to the local tavern on the corner. There was a local tavern right across from the studio called The Friendly, which was not always that friendly actually, because there were a lot of blue-collar rednecks there. There was a point when we had a coke machine in the studio upstairs, and it had eight or ten slots, and we had Coke in only one and the rest had cheap beer that we put in there. We made it free, we put duct tape in so if you put fifty cents in or whatever it would drop right back down so the beer would drop down and you could take the money out of the coin return and put the money back in.

to the local tavern on the corner. There was a local tavern right across from the studio called The Friendly, which was not always that friendly actually, because there were a lot of blue-collar rednecks there. There was a point when we had a coke machine in the studio upstairs, and it had eight or ten slots, and we had Coke in only one and the rest had cheap beer that we put in there. We made it free, we put duct tape in so if you put fifty cents in or whatever it would drop right back down so the beer would drop down and you could take the money out of the coin return and put the money back in.

PHAWKER: In Billy Corgan, leader of the Smashing Pumpkins, you found a kindred spirit who was willing to meticulously craft an album even if that meant spending days getting a drum sound right or a guitar tone right or recording 45 takes of a vocal.

BUTCH VIG: I found a kindred spirit in Billy in the sense that he wanted to make an amazing sounding record. Now it’s so easy to make things sound perfect, to tighten things up and edit, drums or guitars or whatever and fix vocals, back then you had to play it. As good as they were, we recorded a lot and we did a lot of takes. Making Gish was the first time I ever had a proper budget. Before then I’d done hundreds of records in a couple days. I think we had about 30 days to record and mix Gish, and to me, that was like Steely Dan time.

PHAWKER: Is it true that you were only able to convince Kurt Cobain to double track his vocals by telling him that John Lennon used to do that?

BUTCH VIG: That’s true, because he just felt like it was fake, and as much as I knew, I told the band that, that I wanted to double some things, I wanted to go back and overdub some things, because we need to make this sound on a record, when someone wakes up in the morning and this is playing on their little alarm clock radio, we need to make the record sound as intense there as if you were standing in front of the band playing live in a room.

PHAWKER: In the wake of the overwhelming success of Nevermind and perhaps  responding to the holier than thou underground types that were complaining that the album’s production values represent some kind of sellout of punk rock purity, Cobain told writer Michael Azerrad “looking back on the production of Nevermind, I’m embarrassed by it now. It’s closer to a Motley Crue record than it is a punk rock record.” How did you respond to reading that?

responding to the holier than thou underground types that were complaining that the album’s production values represent some kind of sellout of punk rock purity, Cobain told writer Michael Azerrad “looking back on the production of Nevermind, I’m embarrassed by it now. It’s closer to a Motley Crue record than it is a punk rock record.” How did you respond to reading that?

BUTCH VIG: I remember reading it at the time and it bummed me out because when we finished the record, the band was over the moon with how it sounded. They worked really hard to get that record super tight but what happened was when you sold fifteen million records you cannot maintain your punk credibility and say “Man, I’m so glad we sold fifteen million records.” You have to walk away from it. He had to diss it, in a way, for himself and how he was perceived by the public. I wish he was around today because I have a feeling he would have gone back to love it.

PHAWKER: The Nevermind sessions at Smart started in April of 1990. It was just supposed to be a little indie record for Sub Pop. After a number of the tracks were recorded, the sessions stopped when Cobain blew his voice out on “Lithium.” The plan was that they were going to come back and finish the record there but instead they sort of used those tracks as a bargaining chip to get a major label deal — and at that point “Smells like Teen Spirit” was not even written. So if he hadn’t blown his voice, the album probably would have been finished at Smart, without “Smells like Teen Spirit,” and would have become just another hip little indie record on Sub Pop instead of the generation-defining zeitgeist-embodying blockbuster we all know and love?

BUTCH VIG: Correct.

PHAWKER: So, moving forward, you form Garbage with Smart Studios co-owner Steve Marker, which was a big break from the punk sound of the music you had become famous for producing.

BUTCH VIG: Well, by the time I started Garbage, and by the time anybody heard of Nirvana or Smashing Pumpkins, I had done, I swear to god,  a thousand punk rock records, and I was getting tired of just guitar, bass, and drums, especially after Nevermind took off. I started getting calls, people thought I had some magic formula and if I could just plug that into, whoever it was, whether it was a singer/songwriter or a blues artist or a hair metal band, I knew how to change them into an alternative grunge band and I wasn’t interested in doing that.

a thousand punk rock records, and I was getting tired of just guitar, bass, and drums, especially after Nevermind took off. I started getting calls, people thought I had some magic formula and if I could just plug that into, whoever it was, whether it was a singer/songwriter or a blues artist or a hair metal band, I knew how to change them into an alternative grunge band and I wasn’t interested in doing that.

PHAWKER: After a lengthy hiatus, Garbage is about to embark on a tour in support of a new and intriguing record called Strange Little Birds.

BUTCH VIG: Yeah, it’s gotten a lot of great press despite being such a dark album, it’s definitely the darkest album that we’ve made. I think there’s something about it that has resonated with people. Part of it is that we took some of the rock and roll out of it, the album is much more sort of cinematic and atmospheric, and I think the music works, arrangement wise, really well with Shirley singing and her lyrics. She has sung some of the most powerful performances she’s yet recorded on Strange Little Birds. I think you can hear that, there’s an immediacy and an emotional vulnerability to the performances out there that we would have fussed over more in the past in Garbage, but at this point in  our career we’re trying to leave things alone and be a little more spontaneous with them and I think that translated a lot to the vibe on the record.

our career we’re trying to leave things alone and be a little more spontaneous with them and I think that translated a lot to the vibe on the record.

PHAWKER: Smart Studio closes in 2010 because…?

BUTCH VIG: The music business has changed and so has recording technology, the D.I.Y. attitude has taken on a whole new meaning because someone can record on their laptop in their bedroom, so why pay $100 dollars to go in the studio when they can keep that money in their pocket. The studio got used less and less, and we couldn’t get anybody. We were literally offering $100 dollars a day to come in and track, just pay for the assistant engineer and you can use the studio and it just wasn’t getting used. Between insurance and keeping overhead and heating and bills and all that kind of stuff, we couldn’t let it sit there with closed doors, so we finally decided to pull the plug and sell it.