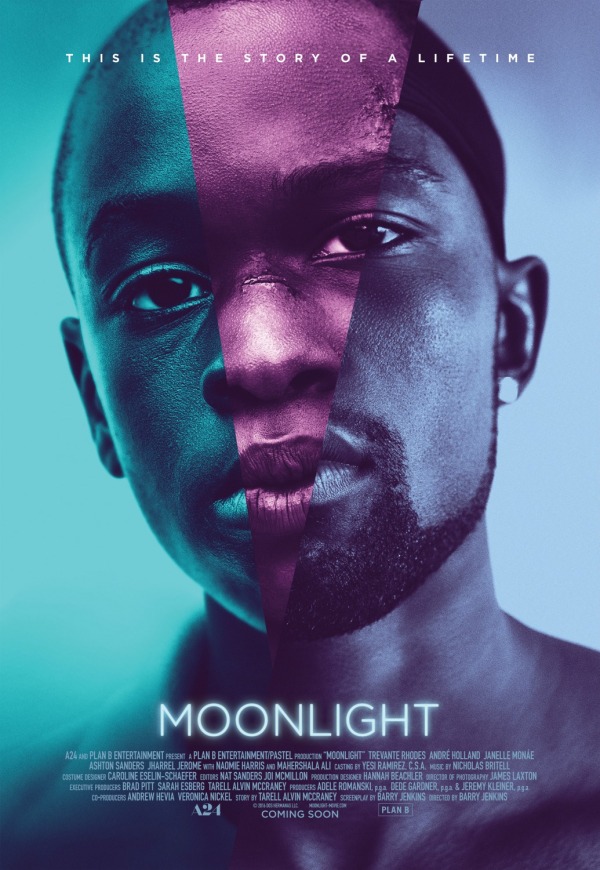

Moonlight (2016, directed by Barry Jenkins, 110 minutes, U.S.)

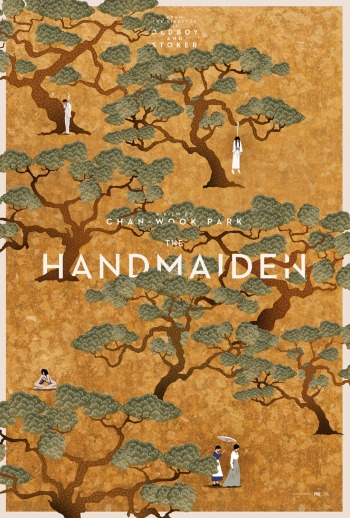

The Handmaiden (2016, directed by Park Chan-wook, 144 minutes, South Korea)

![]() BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC A couple years ago, I climbed aboard the critical pile-on for Richard Linklater’s ten-years-in-the-making epic, Boyhood, an intimate coming of age story that grew up alongside its young star. Watching a kid grew over a decade in a fictional film was an intriguing novelty and Linklater has a genial way with actors but through all the film’s pleasures was a gnawing thought that this kid’s life and experiences at their heart were not very interesting. Relatable yes, but so universal as to be almost dull, with an immersive realism standing in the place of real drama.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC A couple years ago, I climbed aboard the critical pile-on for Richard Linklater’s ten-years-in-the-making epic, Boyhood, an intimate coming of age story that grew up alongside its young star. Watching a kid grew over a decade in a fictional film was an intriguing novelty and Linklater has a genial way with actors but through all the film’s pleasures was a gnawing thought that this kid’s life and experiences at their heart were not very interesting. Relatable yes, but so universal as to be almost dull, with an immersive realism standing in the place of real drama.

Barry Jenkins second feature seems almost like an answer to Linklater’s film, bringing light to the hidden privilege of Linklater’s Boyhood family while sharing a similarly immersive realism into our young man’s journey. Three actors play the character of Kevin: Jadan Piner at the age of nine, Jharrel Jerome at 16 and Andre Holland who portrays Kevin as a young man. We check in with Kevin three times throughout his life, in episodes that don’t build to melodrama but each quietly forging the man he is on his way to becoming. Starting out in the world with an unstable home life and an addicted mother, Kevin’s life could easily be milked for tragedy but Jenkins, with a minimal of sentimentality, focuses on the quiet hope and charity that keeps people afloat in tough times. Kevin, is fathered by a thoughtful older drug dealer in Part One (each given on-screen titles), is an awkward gay teen in Part Two and in Part Three is shown in his twenties, trying to piece his thwarted life together and find out who he is. Yet it’s Jenkins unforced, observational strategy that defines the film more than any narrative, a rare American director that has built his style around having you extract the meaning of many scenes rather than underlining every plot point before it arrives, and the dreamy and luminous photography by James Laxton (of Kevin Smith’s Tusk) adds a poetry to young black lives that is rare to see on screen.

Jenkins’ 2008 debut Medicine For Melancholy, with The Daily Show‘s former correspondent Wyatt Cenac was a modest success that revealed a major talent (I listed it in Phawker’s “Best of the Decade” in 2010) but Moonlight shows him developing his talent in surprising ways. Where Melancholy was filled with talking, causing some to dub it a “black Before Sunrise” (again with the Linklater comparisons) Moonlight gets more out of silences than any recent U.S. film I can remember. At times Jenkins seems to conscious evoke Charles Burnett’s 1978 film Killer of Sheep, that lonely touchstone of black art cinema. Burnett’s difficulty in getting his films funded is well-known, it is hopeful to think that the hype that has surrounded Moonlight might allow Jenkins to win the on-going struggle to bring African American directors’ work to art house cinemas.

__________

Park Chan-wook’s The Handmaiden is another case of worthy advance hype. I was dazzled by the South Korean director’s modern classic Oldboy, loved his take on vampire folklore in Thirst but felt a little let down by his English-language debut, Stoker. With The Handmaiden Park is back to writing his own screenplays, adapting Sarah Waters’ Fingersmith (already a BBC mini-series) and relocating the Victoran-set novel to 1930s South Korea, then under colonial Japanese rule. After the genre-bent subject matter of Park’s body of work, I can’t say the idea of a handmaiden’s steamy affairs peaked my excitement but make no mistake about it, The  Handmaiden is pure Park, full of ingenious intrigue and jaw-dropping developments. It’s really one of our modern cinema masters working on all cylinders.

Handmaiden is pure Park, full of ingenious intrigue and jaw-dropping developments. It’s really one of our modern cinema masters working on all cylinders.

Sookie (Kim Tae-ri) is a pickpocket orphan sent to live with Lady Hideko, a Japanese heiress who is being courted by a con man Count (Ha Jung-woo). Sookie is expected to soften the Lady up for the Count’s wedding proposal but the two women end up falling in love (the explicitly sexual kind) and the plan gets…complicated. There’s a lot more to it than that, there’s a wealthy uncle who collects vintage erotica, the ghost of a hanged aunt and then plot twists, plot twists, plot twists. And just when you think it is getting all too scenic and precious, Park plunges some horrible, morbid detail right out into the open.

Park throws a lot of balls in the air narrative-wise, multiple timelines, flashbacks, switching (with the help of colored subtitles) between the Japanese and Korean language, but all those artful, symmetrical compositions remind you that you’re in the hands of a master as the final third’s breathless finale finally lays bare the films numerous deceptions. Park’s ghoulish and ultimately upbeat tale is a bravura work, begging for the biggest screen available where it’s bound to slacken jaws everywhere.