BIRTH OF A NATION (2016, directed by Nate Parker, 120 minutes, U.S.)

![]() BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC I’m surprised how often I’ve heard critics and commentators sigh about, “another Hollywood film about slavery.” Has Hollywood really exhausted the subject? The 1975’s potboiler Mandingo, Spielberg’s overly-stately Amistad, Jonathan Demme’s mishandled adaptation of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Tarantino’s leering Django Unchained and Steve McQueen’s 2013 Academy Award-winner 12 Years a Slave; I’d say that is five major efforts over the last forty years. Like the Jewish Holocaust, the era is ripe with raw emotions and dramatic possibilities, but like the American genocide of the First Nations people, the history of American slavery is, if not taboo on screen, it is a subject that the public in general is not comfortable discussing. It’s almost seems as if people thought the ’70s mini-series Roots was mea culpa enough, the citizenry should now put the subject to rest.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC I’m surprised how often I’ve heard critics and commentators sigh about, “another Hollywood film about slavery.” Has Hollywood really exhausted the subject? The 1975’s potboiler Mandingo, Spielberg’s overly-stately Amistad, Jonathan Demme’s mishandled adaptation of Toni Morrison’s Beloved, Tarantino’s leering Django Unchained and Steve McQueen’s 2013 Academy Award-winner 12 Years a Slave; I’d say that is five major efforts over the last forty years. Like the Jewish Holocaust, the era is ripe with raw emotions and dramatic possibilities, but like the American genocide of the First Nations people, the history of American slavery is, if not taboo on screen, it is a subject that the public in general is not comfortable discussing. It’s almost seems as if people thought the ’70s mini-series Roots was mea culpa enough, the citizenry should now put the subject to rest.

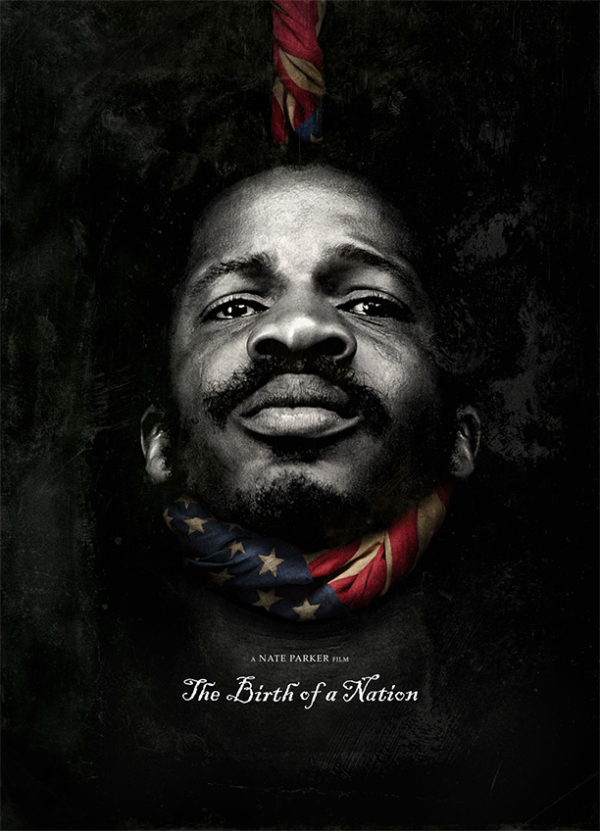

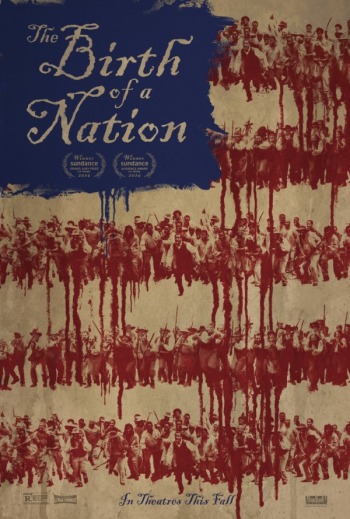

Claiming the name of long-form narrative cinema’s racist genesis for his own, Nate Parker’s film Birth of a Nation has arrived with more hype, controversy, and cultural relevance than any mere movie should have to shoulder. Telling the story of Nat Turner and his slave rebellion might lead you to expect Nate Parker’s directorial debut to be as revolutionary as the true events it documents. It isn’t. Although  watching black characters carry out justifiable violence against their oppressors may be rare in Hollywood cinema, Parker’s film is told with the sort of stock scoring and direction you might find in any well-mounted TV program (perhaps such stylistic conservatism accounts for the diminished roles for women as well). But what does feel revolutionary is the depiction the routine dark reality of slavery. Polite slaves have littered the silver screen since the invention of cinema but the dystopic vision of a world that turns on treating people like animals has the power to deeply disturb. Knowing that black citizens in America still channel this type of oppression is a fact with which a viewer cannot sit comfortably.

watching black characters carry out justifiable violence against their oppressors may be rare in Hollywood cinema, Parker’s film is told with the sort of stock scoring and direction you might find in any well-mounted TV program (perhaps such stylistic conservatism accounts for the diminished roles for women as well). But what does feel revolutionary is the depiction the routine dark reality of slavery. Polite slaves have littered the silver screen since the invention of cinema but the dystopic vision of a world that turns on treating people like animals has the power to deeply disturb. Knowing that black citizens in America still channel this type of oppression is a fact with which a viewer cannot sit comfortably.

The film’s dominant emotion is sorrow, not anger. Nat is shown as a child, briefly knowing friendship with the boy Samuel Turner, who will grow up (as portrayed by an irritable Armie Hammer) to be his owner. Samuel may not share the sadism we see portrayed by country slave tracker (Jackie Earle Haley, using the repulsiveness that won him the role of Freddy Kruger in the Nightmare on Elm Street reboot) but Samuel is a hard drinker and far from Nat’s ally. Nat was taught to read Bible verse from a young age by Samuel’s sympathetic sister Elizabeth (Penelope Ann Miller) and reading allows him to place his people’s slavery in another context and see the injustice. This leads to fiery oration where Nat delivers sermons whose subversive messages of freedom are not lost on the slaves in his audience. Much of the film lingers over Nat’s observing one injustice after another in his travels, until violent recourse seems not just inescapable but a necessity.

When the violence finally does break, those who die at the hands of the rebellion have exhausted all sympathy. One is even shown to have a slave child in their bed, just in case you wondered whether they had it coming. But if this violence is mostly abstracted and off screen, the violent response from the mobs protecting the ways of the Old South are muted too. While Nina is singing “Strange Fruit” and the black men and women are hanging from trees, Parker himself seems to shy away from the horror underlying the picture, having them all serenely floating in the air like angels rather than hanging heavily from their necks. Maybe to bring these realities forward would have made the story into a horror film, maybe taking things that far would have lost the audience the film is designed to catch. Still, there’s plenty to trouble your soul in Birth of a Nation, if maybe just a little too much of a desire to keep its audience entertained. But there aren’t many movies out in theater right now whose stories feel so desperately necessary to be told.