WASHINGTON POST: The first volume of Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning landmark “Maus” landed 30 years ago, and ever since, I’ve wondered when I would encounter another epic historical memoir that, in stirring word and stark picture, might achieve some of the same power as that game-changing graphic novel.

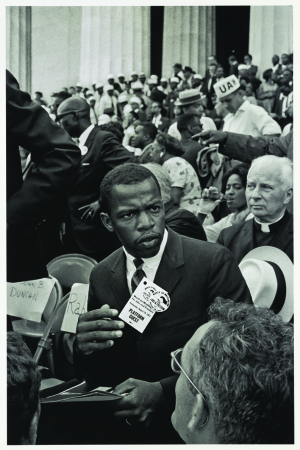

The closest American peer I’ve found to “Maus” has arrived. The final volume of Rep. John Lewis’s “March” trilogy is a milestone. This work is the last movement in Lewis’s personal symphony of civil-rights memories. Lewis [pictured, below right] might be a nonviolent protester, but in terms of delivering drama, the hero packs quite a punch.

This summer, when the congressman led a House Democratic sit-in over gun control, Lewis’s book collaborator and artist Nate Powell said, “I love it when he speaks about ‘dramatizing the situation.’ ” Powell was referring to Lewis’s gift for magnifying aspects of a conflict to provide a concrete sense of what is at stake. That might as well have been a guiding creative credo for every volume of “March,” each one illustrated by Powell and co-written by Lewis and his comics-loving staffer, digital director Andrew Aydin.

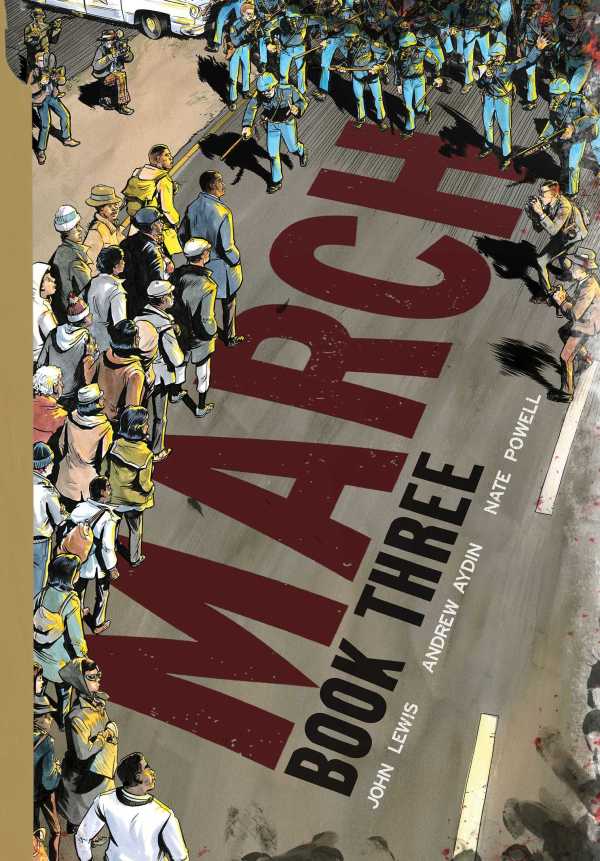

Last month, the second installment in this gripping trilogy received the Eisner Award — the nearest thing to an Oscar for comics — for Best Reality-Based Work. This month, the even-more-accomplished “March: Book Three” culminates the mid-’60s drama that spans from Albany to Alabama. What the authors achieve with this conclusion is a window into living history that could not resonate more deeply in a year of political  conventions against the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement and its many battle lines of engagement. MORE

conventions against the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement and its many battle lines of engagement. MORE

THE ATLANTIC: One person who is well-versed in these kinds of racial politics is Representative John Lewis, whose career as a black civil-rights icon and renown as the last living speaker at the famed 1963 March on Washington are now the stuff of legend. Lewis is working to ensure that the hard truths about race in America and his own legacy aren’t erased. His graphic-novel series, March, created by Lewis, his staffer Andrew Aydin, and the award-winning graphic novelist Nate Powell, has been a surprisingly good and critical part of that work. With its final installment, Book Three, due out in August, the series could be both a necessary guide to the past and a warning about the present.

I read all three books in the March series in one go. Even for readers who own the first two, mainlining the 20-year or so time period the series covers has the same effect as bingeing a season of a television show: The themes and cycles that motivate the action and the characters become more apparent. In the case of March, which covers Lewis’s life and perspective on the civil-rights movement of his childhood through the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, the true pervasiveness of American racism and racial inequality in the era is evident, as is Americans’ commitment to keeping it that way.

March: Book One covers the period from Lewis’s boyhood of raising chickens in a sleepy corner of Alabama to him heading off to college, meeting his idol Martin Luther King, Jr., and becoming involved in the Nashville Student Movement’s early protests against segregation. The story details how “The Montgomery Story,” a comic book released in 1956 about King’s involvement in the famous Montgomery Bus Boycotts, motivated Lewis as a youth and likely inspired his own reflections in graphic-novel form. Book two is a longer volume featuring Lewis’s involvement in the Freedom Rides and his eventual ascendance to leadership of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and status as one the “big six” speakers during the March on Washington. Powell richly drew both books in black and white, and the text provides plenty of detail about the history of black activism, detail which will likely be rewarding even for readers who are experts on the era.

But as good as those books are, it is clear that book three is the emotional and narrative climax toward which they’ve been building. While books one and two read like the classic schoolroom Black History Month narrative of a straight line from struggle to transcendence, book three is a story of heartbreak, the pervasiveness of racism, and Pyrrhic policy victories. This is the true story of how civil rights were carved out in America: in the blood of activists. Book three opens with the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. What follows is a cavalcade of violence and a war of attrition between the defenders of Jim Crow and those threatening to overturn it. There are several more deaths throughout book three, and the weight of grief and bitterness that threatens to overcome even Lewis’s supernatural commitment to nonviolence is explored. This was the book that I suspect was written most with an eye towards allegory of current events.It’s impossible not to see the modern Black Lives Matter movement reflected in the violence, including the “Mississippi Burning” of three Freedom Summer activists and the tragedies at Selma. MORE