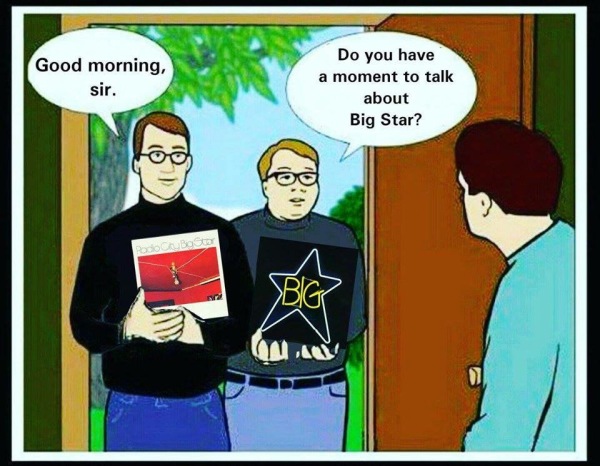

ROCK SNOB ENCYCLOPEDIA: It has been said that the genre of power pop—frail white man-boys with cherry guitars reinvigorating the harmonic convergence of the Beatles, the Beach Boys and the Byrds with the caffeinated rush of youth—is the revenge of the nerds. Big Star pretty much invented the form, which explains the worshipful altars erected to the band in the bedrooms of lonely, disenfranchised melody-makers from Los Angeles to London and points in between.

Though they never came close to fame or fortune in their time, the band continues to hold a sacred place in the cosmology of pure pop, a glittering constellation that remains invisible to the naked mainstream eye. Succeeding generations of pop philosophers and aspiring rock Mozarts pore over the group’s music like biblical scholars hunched over the Dead Sea Scrolls, plumbing the depths of the band’s shadowy history, searching for meaning in Big Star’s immaculate conception and stillborn death.

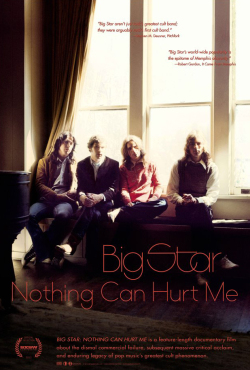

Big Star was the sound of four Memphis boys caught in the vortex of a time warp, reinterpreting the  jangling, three-minute Brit-pop odes to love, youth and the loss of both that framed their formative years, the mid-‘60s. Just one problem: It was the early ‘70s. They were out of fashion and out of time. Within the band, this disconnect with the pop marketplace would lead to bitter disillusionment, self-destruction and death. But that same damning obscurity would nurture their mythology and become Big Star’s greatest ally, a formaldehyde that would preserve the band’s three full-length albums—No. 1 Record, Radio City and Sister Lovers/Third—as perfect specimens of classic guitar pop. That Big Star’s recorded legacy would go on to inspire countless alternative acts is one of pop history’s cruelest ironies—everyone from R.E.M. to the Replace-ments to Eliott Smith would come to see Big Star as the great missing link between the ‘60s and the ‘70s and beyond.

jangling, three-minute Brit-pop odes to love, youth and the loss of both that framed their formative years, the mid-‘60s. Just one problem: It was the early ‘70s. They were out of fashion and out of time. Within the band, this disconnect with the pop marketplace would lead to bitter disillusionment, self-destruction and death. But that same damning obscurity would nurture their mythology and become Big Star’s greatest ally, a formaldehyde that would preserve the band’s three full-length albums—No. 1 Record, Radio City and Sister Lovers/Third—as perfect specimens of classic guitar pop. That Big Star’s recorded legacy would go on to inspire countless alternative acts is one of pop history’s cruelest ironies—everyone from R.E.M. to the Replace-ments to Eliott Smith would come to see Big Star as the great missing link between the ‘60s and the ‘70s and beyond.

There is a dreamy, pre-Raphaelite aura that surrounds the legend of Big Star. Like the doomed, tender-aged beauties in Jeffrey Eugenides’ novel The Virgin Suicides, the tragic career of Big Star would unravel in the autumnal Sunday afternoon sunlight of the early 1970s. The band’s sound and vision hinged on the contrasting sensibilities of songwriters Alex Chilton and Chris Bell. In the gospel of Big Star, Bell is the sacrificial lamb—fragile, doe-eyed and marked for an early death. Chilton is the prodigal son, returning to Memphis after traveling the world, having tasted the bacchanalian pleasures of teen stardom with the Box Tops in the 1960s.

Where Bell was precious and naive, Chilton was nervy and sardonic, but the band’s steady downward spiral would set him on the dark path of personal disintegration — booze, pills, violence and attempted suicide. Years later, he would reinvent himself as an irascible iconoclast and semi-ironic interpreter of obscure soul, R&B; and Italian rock ‘n’ roll. Drummer Jody Stephens, the wide-eyed innocent of the group, and bassist Andy Hummel, the sly-grinning sphinx with the glam-rock hair, were the shepherds in the manger, midwives to the miracle birth. In the aftermath of Big Star’s collapse, Stephens would become a born-again Christian, and Hummel would go on to design jet fighters for the military, anonymous and happy behind the wall of secrecy his job would require. MORE