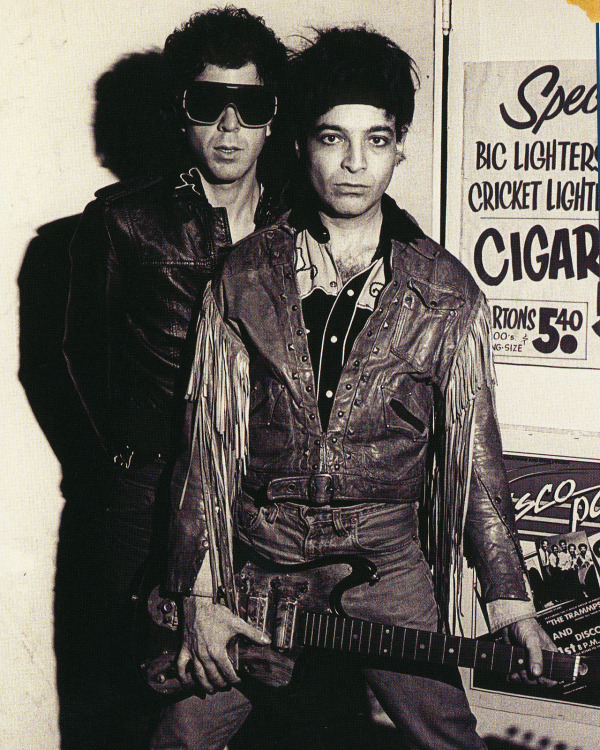

NEW YORK TIMES: Alan Vega, the singer in the minimalist, proto-punk, proto-electro, proto-industrial two-man band Suicide and a prolific musician and visual artist on his own, died on Saturday. He was 78. Suicide, particularly in its early years, was as much a provocation as a concert act. Formed in 1970, it was one of the first bands to bill themselves as “punk music.” With Martin Rev playing loud, insistently repetitive riffs on keyboards and drum machines and Mr. Vega crooning, chanting, muttering and howling his lyrics about insanity, mayhem and death, Suicide fiercely polarized its audiences. “We almost got killed. I love that reaction,” Mr. Vega once reminisced about Suicide’s debut at the Boston nightclub the Rat. “I’d say one half wanted to kill us and one half loved us.” A notorious 23-minute show recorded in Brussels in 1978 turned into a riot; Suicide released a recording of it. Suicide’s music would later be more widely tolerated, recognized as a precursor of electronic dance music and industrial rock.

Mr. Vega was born Boruch Alan Bermowitz on June 23, 1938 in New York City, and grew up in the Bensonhurst area of Brooklyn. He majored in fine arts and physics at Brooklyn College, studying with Ad Reinhardt and Kurt Seligmann. In the late 1960s he was affiliated with Museum: A Project of the Living Artists, a multimedia gallery, studio and performance loft in Greenwich Village, where he experimented with electronic music and made sculptures featuring light bulbs and found materials. He and Mr. Rev played their first shows as Suicide there. Mr. Vega had been galvanized by seeing a concert at which Iggy Pop, lead singer of the Stooges, leapt into the audience and ended the show bloody and triumphant. “It showed me you didn’t have to do static artworks; you could create situations, do something environmental,” Mr. Vega told The Village Voice in 2002. “That’s what got me moving more intensely in the direction of doing music.”

In the trashy, fertile downtown New York City arts world of the early 1970s, Suicide performed at the Mercer Arts Center, Max’s Kansas City and CBGB as well as at art galleries. Suicide’s self-titled debut album was released in 1977. It included a staple of the duo’s live shows, “Frankie Teardrop,” a 10-minute song with a relentless two-note keyboard line and a hissing electronic beat about a desperate factory worker who kills his wife and child. The album received praise in England but negative reviews from The Voice and from Rolling Stone (which would much later place  it in its list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time). In 1978 the duo toured Europe and Britain, opening for Elvis Costello and the Clash; it was often booed and sometimes worse. In Glasgow, Mr. Vega ducked a flying ax. “Everybody came in to see Suicide to be entertained,” he told Ink19 magazine, “and all we did was give them back the street, in all its glory, and that’s what they hated us for.” MORE

it in its list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time). In 1978 the duo toured Europe and Britain, opening for Elvis Costello and the Clash; it was often booed and sometimes worse. In Glasgow, Mr. Vega ducked a flying ax. “Everybody came in to see Suicide to be entertained,” he told Ink19 magazine, “and all we did was give them back the street, in all its glory, and that’s what they hated us for.” MORE

THE GUARDIAN: In 1969, the year before he formed Suicide, a sculptor called Alan Bermowitz went to see the Stooges play live in New York. “Iggy came out and he’s wearing dungarees with holes, with this red bikini underwear with his balls hanging out,” he later remembered. “He went to sing and he just pukes all over, man. He’s running through the audience and shit … He was just wild looking – staring at the crowd and going ‘Fuck you! Fuck you!’… It was one of the greatest shows I ever saw in my life. It changed my life because it made me realise everything I was doing was bullshit.”

If the Stooges instilled a desire to provoke audiences in Alan Vega, as he eventually became, then he lived out his desire beyond his wildest dreams. For years – before people started talking about Suicide as one of the most important bands of the 70s, before it became apparent that their influence was the glue that bound together artists as disparate as Bruce Springsteen, Soft Cell, Sigue Sigue Sputnik and Spiritualized – the thing Suicide were really famous for was inciting audiences to the point where the gig would degenerate into a riot. They probably would have rioted even without Vega goading them – the world just wasn’t ready for a band that consisted of a drum machine, a distorted, droning Farfisa organ and Vega screaming and whooping, like a particularly feral rockabilly singer who had been teleported to the mean streets of 70s New York and suffered a nervous breakdown as a result – but he certainly wound things up further: lashing out with a motorcycle chain, gouging at his skin with safety pins, slapping people in the front row.

Former Sonic Youth drummer Bob Bert saw Suicide supporting the Ramones at CBGB’s in 1976: “I had never seen an act take so much abuse from an audience,” he recalled, “and thus thrive on that intensity.” The 1978 live recording 23 Minutes Over Brussels makes for horrifying, compelling listening: during the performance, one audience member snatched the singer’s microphone in an attempt to make the band stop playing; another broke Vega’s nose. The same year, they supported the Clash in the UK. In Glasgow, someone threw an axe at Vega’s head. Watching National Front skinheads invade the stage in Crawley and assault the duo – Vega’s nose was broken again – the keyboard player from the reggae band at the bottom of the bill had something of a revelation. “I thought, we have to get through to these people,” said Jerry Dammers, of the Special AKA, “and that’s when we got our image together and started playing ska.” Thus did Suicide, on top of everything else, inadvertently spawn the Two Tone movement. MORE

BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN: Over here on E Street, we are saddened to hear of the passing of Alan Vega, one of the great revolutionary voices in rock and roll. The bravery and passion he showed throughout his career was deeply influential to me. I was lucky enough to get to know Alan slightly and he was always a generous and sweet spirit. The blunt force power of his greatest music both with Suicide and on his solo records can still shock and inspire today. There was simply no one else remotely like him. MORE