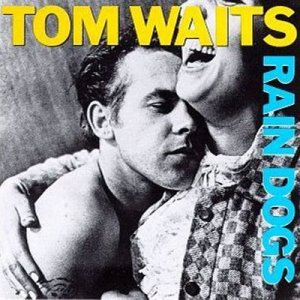

BY JONATHAN VALANIA FOR THE DAILY NEWS In the course of Marc Ribot’s critically acclaimed four-decade career, the chameleonic guitarist has mapped a steady path from edgy lower Gotham upstart to Zen-like American master. Long a fixture of New York’s downtown improv scene, Ribot is probably best known as Tom Waits’ longtime side-man, having played on seven Waits albums and corresponding tours since 1985’s Rain Dogs.

He has lent his six-string sorcery to recordings by Elvis Costello, Robert Plant, the Black Keys, John Zorn, Philadelphia-born soul legend Solomon Burke, and the late, great beat poet Allen Ginsberg. The 22 albums in his discography span splenetic jazz (Electric Masada), noisy avant rock (Ceramic Dog), vintage No Wave (the Lounge Lizards), Haitian folk (the Rootless Cosmopolitans), Cuban son (Los Cubanos Postizos), and soundtracks for imaginary films (Silent Films).

His latest venture is the Young Philadelphians, a collaboration with vaunted Philadelphian jazz masters Jamaaladeen Tacuma and G. Calvin Weston that radically weds vintage Philly soul to the experimental punk-funk sonics of Ornette Coleman’s legendary Prime Time band, which featured Tacuma on bass. The Young Philadelphians will celebrate the release of their debut album, Live in Tokyo, with a free performance Saturday at the 40th Street Summer Series in West Philadelphia. We recently spoke with Ribot about the band, the album, and how it feels to bring this music to Philadelphia.

Huge honor to speak with you, sir, longtime fan. Just let me – just to be clear here, I have to tell you this by law, I’m recording this conversation. Just  so you know.

so you know.

I won’t say anything I don’t want the FBI to know.

First question: can you please clear the air on how your name is pronounced? I’ve heard everything from Ruh-boh to Ry-boh to Rub-oh to Ribb-oh to Ry-bot.

Well, my mom said REE-boh but I’ve heard others say Ra-boh which is also acceptable, but you know, they’re all acceptable. Just don’t call me late for dinner. Ba-da-dum.

Before we go any further, in the interest of full disclosure, I should tell you that when I was in college in 1985 I took Rain Dogs out of the public – out of the Bethlehem, Pennsylvania Public Library and kept it for three years. Listened to it almost every day. When I finally returned it they told me I had been stripped of my borrowing privileges for life. My response was, “totally worth it,” and I still feel that way 31 years later. I do feel bad that others couldn’t hear it, though. But not that bad.

I like that story.

That was, if I’m not mistaken, you’re first gig as a session player. At least your first gig as a session player that was released on a major album?

Yes. It was by no means my first gig as a session player. My first recording was with the [Ivory Coastian kalimba player] Emilio Han. The name of the record was Emilio Han, a Man and His Music because he liked Frank Sinatra. But, I don’t believe – I’m not sure if that was ever commercially released. My first commercial releases, I don’t know if I was credited, were this series of children’s records that were made by the late – produced by the late [John Braden] and they were things like “Barbie and Ken Go to the Rodeo,” and “Learn to Count with Strawberry Shortcake.” And before you laugh, you should be aware that those were the, even though they were never sold in record stores, they were sold in like, you know, toy stores and stuff, they were the second or third best selling mechanical in the year of Saturday Night Fever. So you can find my early stylings on that. My first commercially, really major–

You mean mechanical royalties, right? That’s what you’re referring to?

Well, I mean, mechanical means the actual physical sold objects. The sales of physical objects were second only to the Bee Gees–

That’s really incredible, actually.

Yeah, yeah, and it didn’t even sell in record stores. Those kids buy – those damn kids used to buy a lot of–

Well, they have all the money.

Yeah, yeah, and then the first really record business notable record was with Solomon Burke Soul Alive! which I think is still available on Rounder or something like that. I think it was originally on Rounder and is still available.

You were the guitar player for that live Solomon Burke record?

Yes, I was.

Wow. I love Solomon Burke, I had the chance to interview him before he passed, and there’s another Philadelphia connection that we will be getting to in a second. But before we get into Solomon Burke, I have one more question about Rain Dogs if you don’t mind.

No, go right ahead.

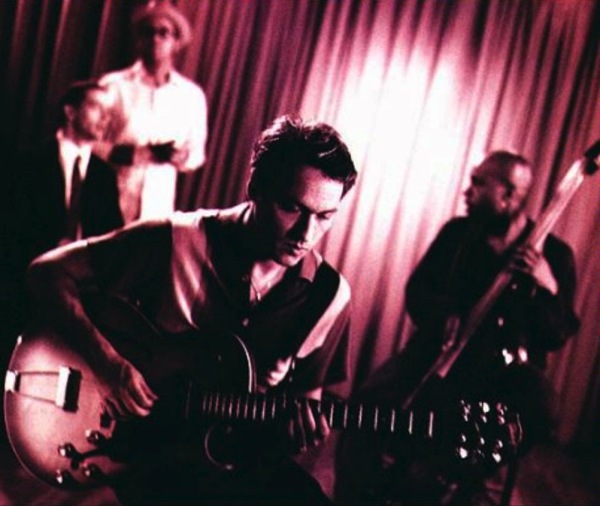

Getting back to the first part of my question here that Rain Dogs was your first proper commercial release. Which is not too shabby considering that the other guitarists on that album are Robert Quine and Keith Richards. Thirty-one years later, what do you remember about making the record or how it came about, or how you came to be involved. [Photo by Dawid Laskowski]

the other guitarists on that album are Robert Quine and Keith Richards. Thirty-one years later, what do you remember about making the record or how it came about, or how you came to be involved. [Photo by Dawid Laskowski]

Well, I was playing at the time with The Lounge Lizards, that record was made I think in ‘84 or something, ‘84 or ‘85. And I was playing with The Lounge Lizards and, by the way, the Solomon Burke Soul Alive! thing was in ‘82 I think. So that’s what I was doing before. And, yeah, Waits was living in New York at the time. I think he just wanted to get, he wanted to get – he wanted to pick up, he was aware something musically was going on in New York and he wanted to pick up on it. And he was going out a lot so I saw him at a couple of gigs I was at, both with The Real Tones, which was the band that went on to back up Solomon Burke and then later with The Lounge Lizards. He sat in with the – I remember he sang “Auld Lang Syne” one New Year’s Eve with The Lounge Lizards and we were all amazed that such a big voice could come out of such a frail dude.

I could totally hear him killing that.

I remember it was like at like 8BC or Limbo Lounge which were, you know, between avenues B and C in the Lower East Side at a time when that was kind of like a drug war zone. Only the most, well, it was a dedication – the fact that a lot of people showed up to hear the gigs was either proof of an extraordinary devotion to music or maybe it was just convenient because they’d just scored. I would say the audience was mixed. So anyways, Waits was picking up on New York bands and I guess he heard me play with The Lizards and he wanted me to play on that record and we actually did a rehearsal and I remember because that’s where I met, I think at the rehearsal I met Ralph Carney and Greg Cohen and I think Michael Blair was there, I’m trying to remember who was drumming on the rehearsals. But anyway, so we ran down the material, but not too much, you know, we just jammed on it a little bit. And then I showed up at the recording session and I remember a lot about the recording session. It was at, I think at the old RCA studios. I mean do you want me to talk about that?

Sure, please. Whatever, you – I’m happy to hear as much as you can tell me.

It was remarkable because the studio was one of these throwbacks to the time when the labels owned the studios.And it was a studio that had been going, clearly, at least since the 50’s. A big beautiful room and we were just set up in a little clump in the middle of it. You know, because I guess Tom wanted to get, like, a live feeling going in the recordings but the room was built to record orchestras and the technology – so the room itself was beautiful, but like the technology hadn’t been quite updated, like I remember I was trying to find an extension cord so I could plug in my amplifier in the middle of the room and nobody seemed able to find one so we had to send downstairs. And the amps were these big old Ampeg amps, that you know, I mean, they were not what you think would have been in a studio, anyways, or not what was in most of the other studios at that time. So, yeah, I just remember the, you know–

So, were a lot of those songs were tracked with the band playing all together or, I always assumed there was a lot of overdubbing.

No, it was tracked with the band playing together. There was some overdubbing but it was mostly the band playing together and I think sometimes Tom went in and re-did his vocals. That might have happened. Although, I think, my memory is that the basic tracks went down with all the bass marimba and all that stuff was on the basic track. Ralph Carney, the sax, was on the basic track.

One last question on Rain Dogs and we’ll move forward. “Jockey Full of Bourbon” is probably my favorite Tom Waits song and your solo on that song is probably my favorite guitar solo of all time after, of course, Dave Davies solo on The Kinks’s “You Really Got Me” which is the essence of rock and roll distilled down to 15 seconds.

Wow.

What can you tell me about how that song came together? Did he play you a version of it that was close to what it turned out to be? Were you guys kind of making this all up on the spot or was it somewhere in between?

Well, I think, it was a long time ago, but generally I think Tom just played a rhythm on congas you know, or strummed it on his guitar. Once he was convinced we had the right groove, I mean the chord structure on that tune is not really complicated. It’s basically, by the way, it’s a kind of a Caribbean bomba you know, it comes from Caribbean music.

You can hear the Cuban in there.

Yeah, Cuban, it’s a lot of Caribbean party music. You can hear plenty stuff, tunes with similar structure so. And at one point he might have even played some sc ratchy cassette of some Caribbean artist, maybe, I don’t know, the Mighty Sparrow or somebody to give an idea of a groove that he was looking for but I don’t think it was on that tune. Anyways, so he gave us an idea of the groove, we played it, I think I maybe overdubbed parts of the solo but I don’t really remember. It was a long time ago.

ratchy cassette of some Caribbean artist, maybe, I don’t know, the Mighty Sparrow or somebody to give an idea of a groove that he was looking for but I don’t think it was on that tune. Anyways, so he gave us an idea of the groove, we played it, I think I maybe overdubbed parts of the solo but I don’t really remember. It was a long time ago.

Moving onward, actually moving backwards for second: Solomon Burke. Solomon Burke loved to tell stories. Do you have favorite story that he might have shared with you or do you just have a story about working with solomon Burke that you’d like to share?

You know, first of all, Solomon was great. Just the most magnetic performer, I mean, the most magnetic performer I’ve ever worked with and I’ve worked with a few. But, you know, like, he had this unbelievable ability to, I mean, you know how every performer says “everybody clap your hands,” or “everybody get up now,” you know, like cliches, right? When Solomon Burke said “everybody clap your hands,” everybody clapped their hands. When he said, “everybody get up now,” everybody got up. It was a little scary. Although, I think, when I first started working with him he was at least 250 pounds and I believe went north of that, women would come up during his performance and literally drape themselves on him and he would kind of gracefully, gently brush them off, you know, without, you know, interrupting his vocal at all. So, I mean, wow, the guy had a musical talent and personal magnetism that was awesome in every sense of the word. So, I don’t know if, should I tell you–

[off the record discussion of the Solomon Burke matter]

Onto the new album. The premise of the new album was to combine the Philly International Sound with, as per the liner notes, “the harmolodic mind-set of the saxophone genius Ornette Coleman’s electric Prime Time band.” Tell us about that band and why it’s important to you.

First of all, it knocked my socks off. I just loved the sound. If you want to hear what I’m talking about, check out Of Human Feelings, which is for me an amazing record. I hear it as his way of working with North Philly funk. He transposed the keys freely so you could play the motif in different keys, backward, forward, upside down.

Can you explain Ornette Coleman’s concept of harmolodics in layman’s terms?

It’s a very dense concept, and I would not be so bold as to pretend that I could explain it, but what I heard in Ornette’s music was the idea of emotive interpretation that leaves room for the new idea that seems to come from left field. So, it’s not a rigid system, it’s a system that incorporates inspiration, error, and chance. MORE