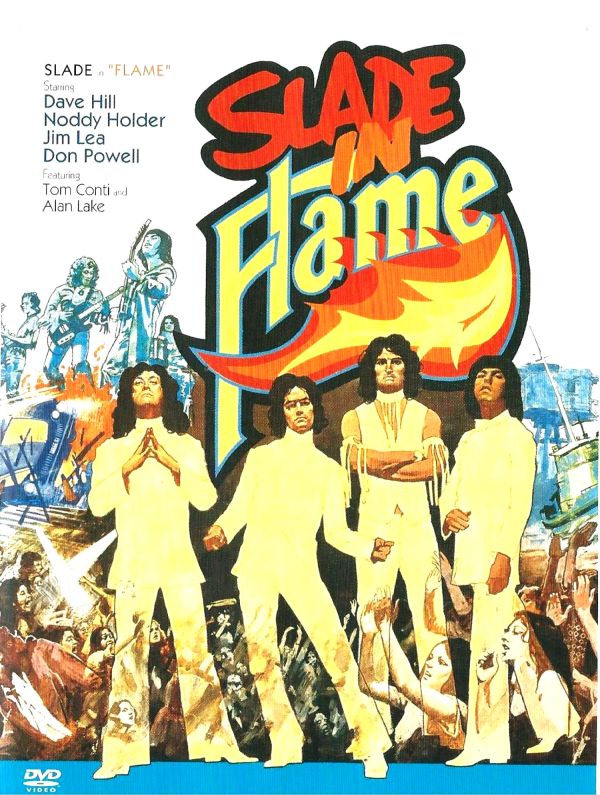

SLADE IN FLAME (1975, directed by Richard Loncraine, 86 minutes U.K.)

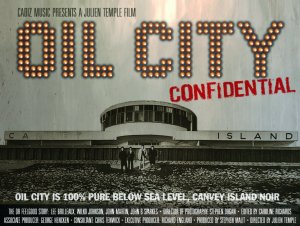

OIL CITY CONFIDENTIAL (2009, directed by Julien Temple, 106 minutes, U.K.)

![]() BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC British rock gave us plenty of adorable mop tops and fey dandies but they also have a long tradition of rough and tumble r&b, rock and blues bands whose fan base ran strong beyond the sophisticated borders of London and into the wilds of the country’s midlands. This month’s double bill joins two rather different films about two different bands, navigating the wild waters of the 70s music industry. Slade in Flame is the 70s glam band’s fictionalized vision of the rock world of 60’s England and 2009’s Oil City Confidential is a romantic look back by documentarian Julien Temple at the furious rise and fall of “Pub Rock” giants Dr. Feelgood.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC British rock gave us plenty of adorable mop tops and fey dandies but they also have a long tradition of rough and tumble r&b, rock and blues bands whose fan base ran strong beyond the sophisticated borders of London and into the wilds of the country’s midlands. This month’s double bill joins two rather different films about two different bands, navigating the wild waters of the 70s music industry. Slade in Flame is the 70s glam band’s fictionalized vision of the rock world of 60’s England and 2009’s Oil City Confidential is a romantic look back by documentarian Julien Temple at the furious rise and fall of “Pub Rock” giants Dr. Feelgood.

Glam rock stars Slade were never as huge in the U.S. as they were across Europe, where they had 17 consecutive Top 20 hits in the early 1970s, more than T-Rex or Bowie. Slade had some success here as well although they’re probably best-remembered today for supplying the pop metal band Quiet Riot with both of their hits, “Cum On Feel the Noize” & “Mama We’re All Crazee Now.” Slade’s success was at its peak in 1974 when their manager Chas Chandler (formerly the Animal’s bassist and manager of Jimi Hendrix) thought the time was ripe for a Slade film.

Bushy-haired Slade frontman Noddy Holder voted down the scripts that called for sped-up comedic hi-jinks from the band and picked a script about a working class band’s rise-and-fall in the record business in the late 60s (set in an era just six or seven years before the film’s production) written by Andrew Birkin (co-screenwriter of the medieval mystery The Name of the Rose and brother of pop star Jane Birkin). Noddy thought the arc of the narrative in Birkin’s script was great, but that the details of the story were all wrong. To fix this, Slade invited Birkin and first-time director Richard Loncraine (director of the dark 1985 vehicle for Sting, Brimstone and Treacle as well as the stylish Ian McKellan 1995 feature of Richard III) to come along on their American tour, where the duo observed the band and interviewed them about their experiences in rock and roll. Birkin incorporated the stories the band related, giving the film a natural realism that transcends the usual cliches of the rock movie genre.

Slade in Flame oozes that sort of gritty quality people love about 70s films, the band emerges from out of a midlands steel town where their friends and family still work. The guitarists’ homelife is only viewed through the mail slot where his grandmother shrieks and curses at the tax collectors. We see the band Flame (the four members of Slade, all quietly confident basically playing themselves) in their element, playing to dancers in dirty little nightclubs, haggling with violent management and horsing around with each other the way guys stuck in little vans for hours on end will do. Soon, they dump their old manager when upper crust young businessman Tom Conti (in his debut) bankrolls a recording session and ushers them into the bigtime.

Slade in Flame focuses on economics and class in a way that its American counterparts would likely ignore. Tom Conti’s character, a young man playing a with his family’s old money, is too disinterested to be a villain. He may bristle at the band’s working class manners and he won’t even feign interest in their music but he isn’t Hellbent to rip them off. But with the family business interests calling him, their manager seems like he could pull the plug at any moment, sending their fates with it.

Slade was proud that they could bring the little corner of the world they knew to big screen in 1975 but their fans were lukewarm to the bleak details among the laughs, and even a cool batch of new Slade songs couldn’t put butts in seats. Years later, Slade in Flame seems like one of the most accomplished rock films of the 70s (a spotty lot indeed) offering a punchy mix of honest Spinal Tap-like madness with a jolt of that old British “Kitchen Sink” realism.

– – – – – – – – –

Slade rock some crazy-colored jumpsuits as the band Flame but Dr. Feelgood called “bullshit” on such theatricality in the mid-70s pre-punk rootsy genre dubbed “Pub Rock.” The band were dress-up like low-key hoods and played a jumped up bluesy  R& B music that stood out for its fine-tuned excess energy. Led by a surly-looking singer named Lee Brilleaux and a gargoyle-faced guitar-stylist Wilko Johnson, (seen as the executioner in the first two seasons of Game of Thrones) Dr. Feelgood had a devilishly fierce rise and fall told here by roc/doc filmmaker Julien Temple.

R& B music that stood out for its fine-tuned excess energy. Led by a surly-looking singer named Lee Brilleaux and a gargoyle-faced guitar-stylist Wilko Johnson, (seen as the executioner in the first two seasons of Game of Thrones) Dr. Feelgood had a devilishly fierce rise and fall told here by roc/doc filmmaker Julien Temple.

Much like the legend of Springsteen, Dr. Feelgood refined their skills in the bar of a seedy, dying beach resort town, which in the case of Feelgood’s Canvay Islands, also had the presence of constantly pounding derricks which pumped the dirty crude found there. Temple, who sees this film as a piece with the definitive documentaries he made on the Sex Pistols and Joe Strummer, gets to the primal drama of band’s chemistry, with Brilleaux’s emotional id contrasting with Wilko’s more artistic soul. Temple peppers the visuals of the band’s rush of success with wild snatches of forgotten black & white ’50s British crime films.

The clips of Dr. Feelgood in action, particularly Wilko’s slashing, rhythmic guitar style and demonic glare, make it undeniable what the fuss was about this now mostly-forgotten group. But it is the romantic reveries spun by the modern day Wilko, talking about that perfect moment, that makes this film so unusually affecting. Were Dr. Feelgood one of rock greatest bands? Maybe not, but Temple constructs one of the great rock stories out of their trials and triumphs.