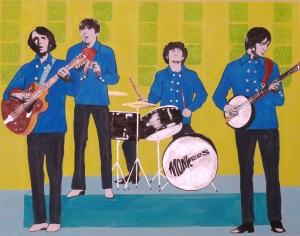

BY JOSH PELTA-HELLER The year 1967 was ground zero for the psychedelic music movement. That year, the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour, and the Rolling Stones released three albums — unthinkable in today’s music marketplace — Flowers, Between The Buttons, and Their Satanic Majesties Request. It was a hell of a year for music, a year that heralded the psychotropic metamorphosis of the pop paradigm. It was also the year that The Monkees sold more records than the Beatles and the Stones combined — an astonishing feat by anyone’s measure. Engineered in a veritable Hollywood laboratory, the Monkees are widely regarded as the first boy band, assembled by television company execs and talent scouts with an ear for a hit and a mind to maximize commercial appeal and profit.

BY JOSH PELTA-HELLER The year 1967 was ground zero for the psychedelic music movement. That year, the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Heart Club Band and Magical Mystery Tour, and the Rolling Stones released three albums — unthinkable in today’s music marketplace — Flowers, Between The Buttons, and Their Satanic Majesties Request. It was a hell of a year for music, a year that heralded the psychotropic metamorphosis of the pop paradigm. It was also the year that The Monkees sold more records than the Beatles and the Stones combined — an astonishing feat by anyone’s measure. Engineered in a veritable Hollywood laboratory, the Monkees are widely regarded as the first boy band, assembled by television company execs and talent scouts with an ear for a hit and a mind to maximize commercial appeal and profit.

Still, most supergroups fall far short of expectations, both artistically and commercially, and few last longer than an album or two. Having released 12 albums over the course of 50 years, The Monkees are a music biz anomaly whose humor, charm and indelible tuneage had a pervasive and lasting influence on the generations of musicians that followed. John Lennon famously called them “the funniest comedy team since the Marx Brothers.” They inspired Kurt Cobain, were covered by The Sex Pistols and Minor Threat, and sampled by everyone from Deee-Lite to Del The Funky Homosapien, whose famous 1991 debut single “Mistadobalina” loops the hook of the Monkees’ “Zilch,” a deep cut from the groundbreaking album Headquarters that marked their break from the assembly line pop of their Brill Building roots and all-in embrace of the autonomy of their own craft.

In the following interview, Monkees percussionist Micky Dolenz touches briefly on that emerging schism between the band they were created to be, and the band that they wanted to be and ultimately became. For his own part, Dolenz’ ear for melody, harmony and rhythm, and his affinity for pushing the limits of his quirky vocals and songwriting would serve their newer directions in their later years, when bubblegum hits like “Daydream Believer” and “Look Out (Here Comes Tomorrow)” gave way to surreal mindbenders like Dolenz’ “Randy Scouse Git” and “Shorty Blackwell.” And aside from his own compositions, his contributions to the music written by bandmates blazed trails as well — the trippy track “Daily Nightly” from their fourth record, 1967’s Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd., written by guitarist Mike Nesmith, features what’s widely considered to be the first use of Moog Synthesizer on any rock and roll record, purchased and played by Micky. Still, Dolenz holds a clear reverence and gratitude for the early days, singing the hits written for them by Boyce & Hart, Carole King, Harry Nilsson and Neil Diamond. And as the surviving three band members work toward the release of a new record this year — their first since  the passing of singer Davy Jones in 2012 — it’s easy to hear in the first single “She Makes Me Laugh,” written by Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo and sung by Micky, the eminent echoes of the earlier Monkees material that, in Micky’s words, “just worked.” The Monkees play The Keswick Theater on May 28th.

the passing of singer Davy Jones in 2012 — it’s easy to hear in the first single “She Makes Me Laugh,” written by Weezer’s Rivers Cuomo and sung by Micky, the eminent echoes of the earlier Monkees material that, in Micky’s words, “just worked.” The Monkees play The Keswick Theater on May 28th.

PHAWKER: Hey Micky, calling from Philly here…

MICKY DOLENZ: Philly! Love it. My wife’s from Philly. We’re there all the time, out in Huntingdon Valley.. Love Philly. Philly cheesesteaks!

PHAWKER: Where do you guys go for cheesesteaks?

MICKY DOLENZ: I love Philly cheesesteaks. I remember when the Monkees toured, the very first time in the 60’s — ‘67 or 8 — we went to Philadelphia, and somebody must’ve said ‘you guys gotta go and try a Philly cheesesteak!,’ and I’d never heard of it before. And they took us to — I can’t remember if it was Pat’s or if it was, the other one…

PHAWKER: …Geno’s.

MICKY DOLENZ: …yeah [laughs], we must’ve looked like, oh my god, ‘cause I think it was like just after a concert, or a party, or something. So we’re all dressed up in the the hippy rock ‘n roll, you know paisley bell-bottoms and tye-dyed shirts and long hair. And of course in ‘67 you didn’t see much of that on the streets in Philly. And we pulled up to Pat’s in a limo [laughs], and got out, wandering around like a midnight or something. I’ll never forget it, those neon lights. I remember all that neon.

PHAWKER: It’s still just like that…

MICKY DOLENZ: Yeah, oh I go every time I get a chance.

PHAWKER: I gotta tell you before we start, I’ve been a fan since I was a kid, and my first mix tape was actually made by holding up a tape recorder in mid-air, and hitting “record” whenever I could catch a song during a rerun of one of your shows on Nickelodeon. I made a full tape of those songs, and that’s what I listened to when I was a kid,  non-stop. You guys informed my musical taste at large and you saved me in the ‘80s from all the terrible pop my friends were listening to, so thanks.

non-stop. You guys informed my musical taste at large and you saved me in the ‘80s from all the terrible pop my friends were listening to, so thanks.

MICKY DOLENZ: [laughs] very cool, well thank you very much!

PHAWKER: Speaking of that, my first question for you is about how we’ve come to define “pop.” Back in the ‘60s when you guys were big and making music, and the Beatles were big, and other bands — looking back now on that there’s a big overlap between what’s lasted, what we call “classic rock,” and what used to be called “pop.” The “pop” from that time became something that was really important to the generation, rather than something that was sort of more superficial and fleeting. At the risk of beginning to sound like an ornery old man, I feel like in some senses, that definition has changed, and that the pop music of today perhaps won’t have the lasting power and be as important in forty of fifty years as your music still is today, fifty years on. Could you speak a little bit to that, from your perspective?

MICKY DOLENZ: Well I don’t know, I mean that’s a very good point. I don’t know if we could ever really pin down a definitive answer. My hypothesis is a bit involved. Back in those days, in the recording industry, it was very tough to get your record played. There were very few outlets. There were very few sources of distribution. There was only terrestrial radio. There were three channels on the television. And the record companies of course controlled the industry. And that wasn’t a bad thing, because what they would do is go out and hear hundreds of bands all over the country, and then the A&R guys, they were called, would, you know, say ‘wow, these guys are good, they need a little work, they need a little coaching, they need some songs…’ And they would develop — at great expense, I must add — they would develop acts. The act just didn’t all the sudden get lucky and get on the radio. There was a lot of development. They called it artist development — A&R, artists and repertoire. And so, the cream sort of rose to the top, because there wasn’t that many outlets for music, so the good stuff — the great stuff — tended to rise to the top and get heard.

Now of course that entire mechanism doesn’t exist anymore. Basically there are no major record companies. There’s no artist development. There’s nobody out there really that are helping guide and nurture songwriters or singers or acts anywhere. So there’s just so much stuff, and so many groups, and so much you can get on the internet now. And you could hardly make a living, if you’re a new act, because of everybody just stealing the music, you can hardly make a living just selling actual CDs or stuff. So I’d say that, you know, that has a lot to do with it.

Back then, there was the Brill Building of songwriters, and you know, we had people like Carole King and Boyce and Hart and Harry Nilsson and Neil Diamond, writing specifically for us, for me, for the show. And you know those people don’t write a  lot of duff tunes! [laughs] So anyway, that has an awful lot to do with it. There probably is really good stuff out there, but how the hell do you find it?

lot of duff tunes! [laughs] So anyway, that has an awful lot to do with it. There probably is really good stuff out there, but how the hell do you find it?

PHAWKER: Back then, when you were making those records, making an album was important as a gesture of capturing an artistic concept that was created and consumed at one time, cohesively. Do you think that the way that music is largely distributed today — as singles, sort of segmented over iTunes and YouTube and as individual files — do you think that has anything to do with the sort of evolution that you’re describing?

MICKY DOLENZ: Yeah, I agree. I think that speaks to the same problem. There’s so much, and it’s all over the place. It’s like television — you know there’s really good television shows out there but how the heck do you find ‘em? [laughs] The TV guide now is the size of a phonebook! The same thing happened in television, you know, when we went on the air, there were only three channels, and the nationwide audience only had three options every evening. I think that’s another point, is shows on television — the demographic was much wider, because a national television show, a network show, it had to be able to play everywhere: on both coasts, the middle of America, the South, the North, the East, the West. So shows tended to have a much wider demographic, and that applied to the writing and the acting and the theme and everything like that. And I think music, maybe the same sort of thing happened. Back then, if you wanted to get on the charts — and there was only one chart [laughs], the Billboard Hot 100 — well you had to appeal to a heck of a lot of different types of people, a heck of a wide demographic. Of course now, all the demographics are very very narrow, you know, it’s called “narrowcasting,” and it’s very very focused. Now you can have a pretty substantial hit with a very very narrow focus.

PHAWKER: In the ‘60s, you were able to make an album, and have it consumed and celebrated as a cohesive artistic volume. These days, an artist’s fans maybe don’t pay as much attention to an album, but can maybe pick and choose a single for purchase, and that single might reach a much wider audience because of say, iTunes or Spotify. Weighing the pros and cons of those eras, do you feel that one or the other model is more valuable to a musical artist?

MICKY DOLENZ: Well, yeah, it’s difficult for me to sort of address that, because I came up and was in an era where what you just described was the common thing. And I was very very successful at it. I think yeah, it’d be lovely, if people could do that. But you’d never get that done today. You’d never get anybody to put up the kind of money to fund. That was the thing the record companies did, they spent tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands — like I mentioned before, developing an act or having somebody in the studio for five months or something like that — because they knew at the end of the day, there was a good chance that it came out good, they could sell it. But now, that’s the great tragedy, if you will,  for new artists, is that there’s nobody that is prepared to invest in their career, because you can’t make any money doing it! And it is a business, you know, there’s two words in show business [laughs]: “show” and “business!”

for new artists, is that there’s nobody that is prepared to invest in their career, because you can’t make any money doing it! And it is a business, you know, there’s two words in show business [laughs]: “show” and “business!”

So yeah, I miss it. I just made a couple of CDs, I have two just over the last couple of years — once called Remember, which is sort of a musical scrapbook of my life, and the other one is Live At B.B. King’s, my live solo show. And Remember definitely had a theme and stuff. But yeah, you’re right, people just go on iTunes and download one single, or one track, and that’s it!

PHAWKER: I’d like to talk a little about the hits that you had, which were sort of the more mainstream songs that everyone knows — “I’m A Believer,” “A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You,” “Last Train To Clarksville,” vs. the other music you guys did, the deep cuts like “Tapioca Tundra” and “Zor and Zam,” that sort of didn’t get as much attention. I know you that you guys got a chance later on in the Monkees’ recording career to put yourselves and your own writing and your own performances into the music maybe more so than you had the opportunity to do early on in the studio. Did you have a favorite sort of era of the Monkees or the type of music the Monkees put out? Was it the psychedelic stuff that was a little bit off-beat, or was it the earlier stuff that you did with which you had more commercial success?

MICKY DOLENZ: You know, that’s a great question. It’s almost like there were two Monkee groups. One was the group on the television show. We were cast into the show, and Donny Kirshner at the Brill Building gathered the material, and they produced the stuff — we had little or nothing to say about what was being recorded or what was being released. And I don’t have complaints about that, because those were some huge, wonderful hits, written by Neil Diamond [for example], some great great Monkee tunes. But then, as you may have heard the story, we fought for the rights to have some sort of a say in the music, and that’s when we started recording some of those songs like you just mentioned. But that in a way is almost another group. It’s a different group, than the Monkees on the television show, living in the beach house. I mean am I making any sense with that?

PHAWKER: That’s the sense that I got, even when I was a kid listening to the records. Do you wish you could give some more attention during your shows to the more psychedelic or eccentric songs in The Monkees’ catalog?

MICKY DOLENZ: Well we do! We have done “Zor and Zam,” and it has been received very well. We’ve done “Tapioca Tundra,” we just did that with Mike, on the last tour. And “Daily Nightly,” and “Mr. Webster,” we’ve done. We have touched upon a lot of that material over the years. Like I said, when we do a concert, you know, we do all the big hits, but then every tour we sort of you know, change it up a little bit, go into the deeper album cuts. And we’ve always sort of done  that, and every song that you mentioned, we have actually done at times.

that, and every song that you mentioned, we have actually done at times.

PHAWKER: But I imagine that, say, “Shorty Blackwell” will never see the light of day at a concert?

MICKY DOLENZ: [laughs] I’ve been asked a lotta times to do that, thank you. That’s a bit of a tricky one to pull off live. [laughs] I wouldn’t mind doin’ it someday, but that’s a little bit of a tricky one. But you know, “Mommy and Daddy” is something that people keep requesting.

PHAWKER: What do you hope to bring to a younger generation with the latest iteration of The Monkees: you, Mike and Peter?

MICKY DOLENZ: Well, you know, we don’t have a whole lot of control over who knows about us. You know, you do your best. A lot of the younger generation hear it through their parents, or their grandparents. And the thing is, those songs — I always dedicate my show to the songwriters, because, it’s those songs, you know, it’s those songs that resonate. And who knows why, you know, you can’t reduce it too much in the scientific sense. But “I’m A Believer,” you know, “(Take The Last Train To) Clarksville,” “Daydream Believer” — they just resonate, you know, something about them — in the performance, in the writing, in the production — just worked! Same with the TV show, you know, something about the comedy and the directing and the writing and stuff. I always look at it that the whole becomes greater than the sum of its parts. And that’s what people respond to.

THE MONKEES 50TH ANNIVERSARY TOUR STOPS @ THE KESWICK MAY 28TH