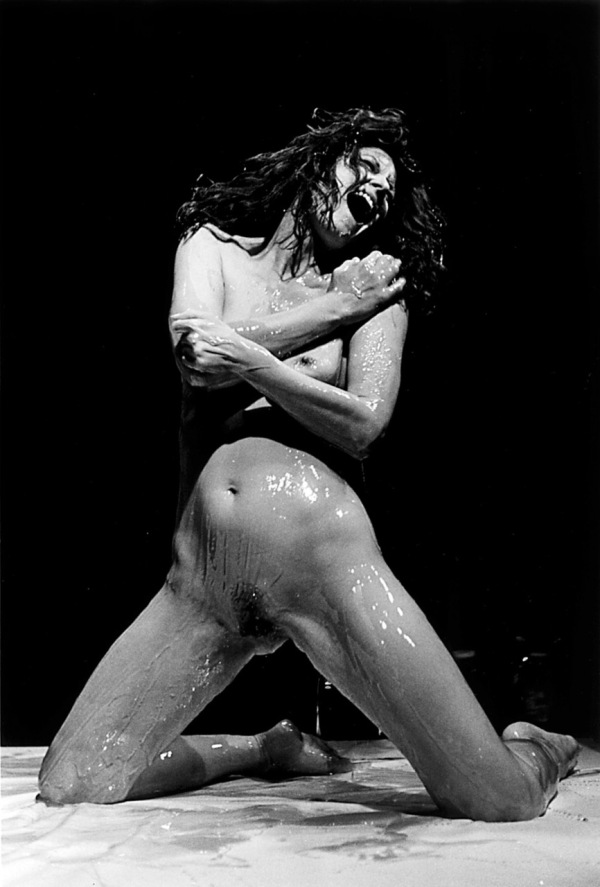

Karen Finley, Return Of The Chocolate Smeared Woman, circa 1994

BY JOANN LOVIGLIO A quarter-century after its release, Karen Finley’s Shock Treatment still packs a punch. It reads like a self-exorcism. Filled with rage, but also humor and a lot of intelligence, it is a skewering of cultural taboos, patriarchy and privilege. She grew up in the Midwest and was soon drawn to the creative hub of 1970s San Francisco, where she hung out at City Lights with Richard Brautigan and Gregory Corso, and had Kathy Acker as a teacher at the San Francisco Art Institute. Finley isn’t one to wax nostalgic about the good old days, however, and says the art world is more exciting now than the days when Jesse “Moral Majority” Helms and his fellow pearl-clutching bigots saw her work as a sign of the apocalypse. She is a Guggenheim Fellowship-winning poet, performance artist, and professor at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. Finley also has a connection to the city — she played Tom Hanks’ doctor in the movie Philadelphia. Finley comes to the Free Library of Philadelphia on Feb. 11 for a reading and book-signing of Shock Treatment.

BY JOANN LOVIGLIO A quarter-century after its release, Karen Finley’s Shock Treatment still packs a punch. It reads like a self-exorcism. Filled with rage, but also humor and a lot of intelligence, it is a skewering of cultural taboos, patriarchy and privilege. She grew up in the Midwest and was soon drawn to the creative hub of 1970s San Francisco, where she hung out at City Lights with Richard Brautigan and Gregory Corso, and had Kathy Acker as a teacher at the San Francisco Art Institute. Finley isn’t one to wax nostalgic about the good old days, however, and says the art world is more exciting now than the days when Jesse “Moral Majority” Helms and his fellow pearl-clutching bigots saw her work as a sign of the apocalypse. She is a Guggenheim Fellowship-winning poet, performance artist, and professor at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University. Finley also has a connection to the city — she played Tom Hanks’ doctor in the movie Philadelphia. Finley comes to the Free Library of Philadelphia on Feb. 11 for a reading and book-signing of Shock Treatment.

PHAWKER: Beyond marking the 25th anniversary of Shock Treatment, can you talk about what else prompted you to embark on this tour? And what struck you when you reread the book, I’m guessing it had been a while?

KAREN FINLEY: The book has remained in print for these past 25 years, so I thought that it would be a time to have it reissued with a new introduction. When I reviewed the book, I was surprised that it wasn’t dated — that it was as relevant as ever in terms of the subject matter and some of the social issues. That’s the primary reason but the other impetus is looking at the book as historical document of the times, of the ‘90s and the turn of the century. I was thinking about the history of the artist as  historical recorder, the importance of the writer, the artist and activist. Being able to come to a library and talk about the book and introduce it as inspiration for young people and all of us … as a way to be responding to all the events and the social issues that are going on now.

historical recorder, the importance of the writer, the artist and activist. Being able to come to a library and talk about the book and introduce it as inspiration for young people and all of us … as a way to be responding to all the events and the social issues that are going on now.

PHAWKER: Shock Treatment really does address subjects we’re still grappling with. Do you feel like we’ve made significant progress, did you think in 1990 that we’d still be dealing with many of the same culture clashes and prejudices in 2016?

KAREN FINLEY: Yes, there’s been progress in terms of gay rights, and the fact that we have a woman running for president, and we have a black president. But the reality is that there’s so much police brutality, misogyny, war, corruption everywhere. What’s happening with the water in Flint, it’s just shocking, so how do we deal with this happening? To be speaking the truth, to have the artist and writer as historical recorder, it’s important for artists, writers, poets, and everyday people to document these things in writing and speak out — even more so than just social media but to have concrete writing on the page.

PHAWKER: It’s interesting to think about the value of the action of writing things on paper, in books, the physical nature of that as opposed to the more ephemeral nature of social media. Protest in the analog versus protest in the digital. Both are important to maintain.

KAREN FINLEY: Absolutely.

PHAWKER: Does it irritate you, or could you care less, when people take this cartoonish view of your work, you know, “the yam lady” kind of thing … is it misogyny at work? You don’t see that kind of a mocking response to the work of the Vienna Actionists or Chris Burden, who also used their bodies to make art.

KAREN FINLEY: When you ask that question right after you ask about the book, then you have an article that becomes about me, and about me minimizing, justifying, denying … that then becomes part of the female packaging in terms of contributions. I think that is true, but I think that the female being reduced, to create this kind of a laughingstock … there isn’t an allowance to be an artist or a contributor to society. I think my career speaks for itself, but sure, that was painful and difficult. If you want to  perpetuate these what you can call urban legends about it, it’s a way of censoring my contributions and diminishing or changing it. Kind of like a photobomb (that obscures or changes the intent of an image) … it’s like putting a controversy bomb in front my message. It is what it is. On another level, I look at it in terms of the great privilege that I’ve had, that I was able to say the things in the first place that were censored. For many individuals, there’s an invisibility.

perpetuate these what you can call urban legends about it, it’s a way of censoring my contributions and diminishing or changing it. Kind of like a photobomb (that obscures or changes the intent of an image) … it’s like putting a controversy bomb in front my message. It is what it is. On another level, I look at it in terms of the great privilege that I’ve had, that I was able to say the things in the first place that were censored. For many individuals, there’s an invisibility.

PHAWKER: What kind of work are you doing now?

KAREN FINLEY: I worked on a project called Sext Me If You Can. I’m very concerned about the humiliation and the shaming of people … it goes back to the earlier question of shaming and humiliation, the issues around sexting and the shame that goes along with their discovery, especially for young people. For the project, people with the museum would commission the opportunity to sext me from the museum and then I would create artwork based on that, and they would receive that artwork. Other pieces I’ve been doing recently, I created a support group Artists Anonymous which is a part parody and part serious look at individuals and their difficulties or their challenges with their addiction to art, their problems with the art world, making art, being a creative person. In terms of my teaching, I’m in the (NYU) Department of Art and Public Policy — after my Supreme Court issues, I did go into education. We offer an M.A. in arts politics, so I teach a class in cultural activism and research and I teach performance as well. It’s about the potential for social change through the arts, whether it’s coming from the artists, or whether it’s coming from NGOs, or curating, or writing, or scholarship, or community-based work, or social practice.

PHAWKER: Do you think the Supreme Court decision involving you and the other three members of the so-called “NEA Four” has created a chilling of speech, or have artists just continued doing their work as usual just with the understanding that they shouldn’t be counting on NEA funding?

KAREN FINLEY: It goes further than just the funding itself. The funding is gone so, yes, there’s a dramatic decrease in support for emerging artists and more of an emphasis on the art market and the profitability of art. These objects become value, they become savings accounts, investments. When you look within the strata of museums and the boards, it’s an economy. But I think that what the Supreme Court case was really about was us questioning the vagueness of using the term of applying “decency” when awarding funding. What we were looking at was the idea of the government being able to use vague terms for applying funding. Yes, people are still making art but it does have ramifications. It’s been disastrous when you think about so many small nonprofits that really helped marginalized communities, connected communities and gave them a voice, and that has ended. These small emerging grants aren’t there anymore. What’s been difficult for larger foundations, philanthropic organizations, even for corporations that would give money to the arts is that the National Endowment for the Arts worked as a place for peer review, and it was extensive … so it became a seal of approval. So if an artist or an organization had been  peer reviewed through the NEA, that would let philanthropic organizations know that they had been vetted already. Now that process isn’t there that acted as a clearinghouse and as a way of connecting all these arts organizations and artists.

peer reviewed through the NEA, that would let philanthropic organizations know that they had been vetted already. Now that process isn’t there that acted as a clearinghouse and as a way of connecting all these arts organizations and artists.

PHAWKER: How about the art scene in New York? Has the skyrocketing cost of living negatively affected it?

KAREN FINLEY: Definitely. In many neighborhoods the cultural life, the artistic life is evaporating. But artists in the most difficult situations still make art. What I think could happen is the art market is almost outpacing itself. There might be other areas that become havens for artists. … also with social media there can be other ways to think about making art outside these criteria, other ways of looking at creative capital.The good news is that I see a tremendous amount of exciting, inspiring, incredible work going on right now. I don’t necessarily believe in the ‘good old days’ — I believe there’s more social practice art, more younger people having a consciousness and awareness of the art and culture of making a difference. I actually feel that right now is more powerful and more positive with more people being interested in creating art and making a difference and standing up and having the courage to create. From my own students to all over the world, I’m seeing artists creating work about identity, about war, about media. There’s a lot of incredible writing. I feel very positive in terms of looking at artist voices. When I started making art in the ‘70s and ‘80s there would be primarily white male artists making work or being given the opportunity. That still is mostly the case with museums and the upper 1 percent, but I do feel very positive seeing the art that’s being made now.

PHAWKER: Final question: What are your thoughts on the presidential race?

KAREN FINLEY: Certainly there’s a lot of people I don’t want to see become president, which includes all of the Republicans. With the Democrats, I’m more interested in Bernie Sanders. [long pause] Yes, I’m more interested in Bernie Sanders.