BY CHARLIE TAYLOR In 1990, 22-year-old Christopher McCandless packed up his 1982 Datsun and embarked on an expedition through the Western United States that would ultimately cost him his life. McCandless, an unsettled individual with a spirit that needed to challenge any obstacles his mind could dream up, finished college in 1990 and appeared to be ready to join the never-ending assembly line of college students headed into professional oblivion. Seduced by the freedom and endless possibilities of the open road, McCandless shocked his parents by turning down the $25,000 fund given to him for his post-college pursuits and disappearing in August 1990. He would never see his family again.

In the course of his travels, he took to calling himself Alexander Supertramp, worked odd jobs (he manned the deep fryer at the McDonald’s in Bullhead City, Arizona and worked at a grain elevator in Carthage, South Dakota) and took all paths in front of him, regardless of their severity. Eventually his paths led him to Alaska.

An avid hiker, but an inexperienced one, Chris McCandless headed into Alaska’s Stampede Trail equipped with little more than a .22 Remington rifle, a tent, and nine or 10 paperback books. Despite the warning of a truck driver that McCandless had not packed enough for the frigid conditions, the young man was unable to break from his strict idealism and untested confidence in his ability to persevere in the wild.

This hubris proved most costly, as McCandless had difficulty killing large game and preserving the carcass. Upon shooting a moose, the intrepid young adventurer took a picture displaying his amazement and pride at his large kill. McCandless’ naivety proved costly, as five days after he had killed the moose, maggots covered it. McCandless, in his journal, described the mistake as “One of the greatest tragedies of my life.”

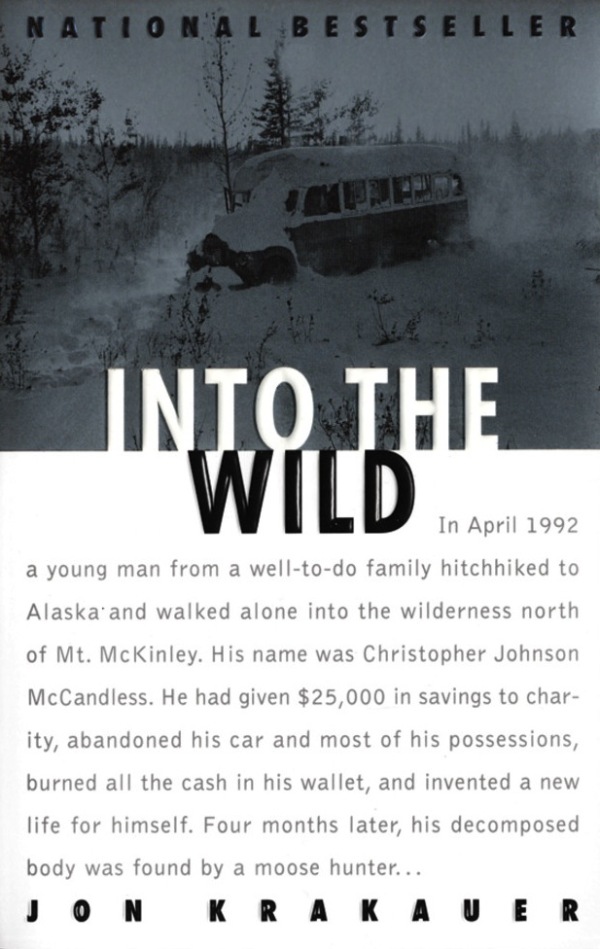

However, his final undoing was the flooding of the Teklanika river which effectively cut off his only way out of the wild. Unable to swim, he returned to the rusted out school bus where he had been sheltering for the preceding four months. It was this bus where McCandless would spend the remaining days of his life. Unbeknownst to McCandless, freedom awaited him only about a mile upstream where the river divided into a series of narrower and thereby crossable channels.

Critically acclaimed writer Jon Krakauer (Into Thin Air, Under the Banner of Heaven) had long been fascinated by the theme of man’s hubris in the face of nature’s greatest tests and the deadly consequences it invites when he discovered the story of Christopher McCandless a few months after his death 1992. Krakauer published a 9,000-word story in Outside Magazine about McCandless’ life called “The Death Of An Innocent,” and later expanded it into a book titled Into The Wild which was published in 1996 and 11 years late made into a motion picture in major motion picture directed by Sean Penn. Into The Wild is the well-researched account of McCandless’ two years adrift in the vast, unexplored places that still remain in modern America.

deadly consequences it invites when he discovered the story of Christopher McCandless a few months after his death 1992. Krakauer published a 9,000-word story in Outside Magazine about McCandless’ life called “The Death Of An Innocent,” and later expanded it into a book titled Into The Wild which was published in 1996 and 11 years late made into a motion picture in major motion picture directed by Sean Penn. Into The Wild is the well-researched account of McCandless’ two years adrift in the vast, unexplored places that still remain in modern America.

“McCandless distrusted the value of things that came easily,” Krakauer writes. “He demanded much more of himself – more, in the end, than he could deliver.” In his last note, McCandless wrote, “S.O.S. I need your help. I am injured, near death, and too weak to hike out of here. I am all alone, this is no joke. In the name of God, please remain to save me. I am out collecting berries close by and shall return this evening. Thank you, Chris McCandless. August?”

The saga of Alexander Supertramp hit close to home. In the spring of 2015, I toyed with the romantic idea of disappearing “into the wild.” Like McCandless, I felt alienated by the path that my life appeared to be taking and decided to venture off to somewhere where I could only rely on myself. But after a couple months on the road, I realized that I did not have the time or the conviction to brave the wild regions like McCandless and returned home. For my 21st birthday, my mother gave me this novel and I could not let it go. That could have been me.

Krakauer writes: “It would be easy to stereotype Christopher as another boy who felt too much, a loopy young man who read too many books and lacked even a modicum of common sense… McCandless wasn’t some feckless slacker, adrift and confused. To the contrary: His life hummed with meaning and purpose.”

Krakauer has a tendency to romanticize the conflict of the individual with the world around him/her (see Into Thin Air) and not surprisingly he considers McCandless a profound, tragic soul seduced by the beauty of the unknown. “My convictions should be apparent soon enough,” Krakauer writes, “but I will leave it to the reader to form his or her own opinion of Chris McCandless.” Krakauer ends his novel with a description of the final self portrait that McCandless took, “He is smiling in the picture, and there is no mistaking the look in his eyes: Chris McCandless was at peace, serene as a monk gone to God.”

McCandless was a tragic soul, but no more profound than any other 21 year old who doesn’t even know how much he doesn’t even know. That serenity that McCandless searched for in his journey accompanied him to his death, but I am dead certain that given the option he would have traded this acceptance of death for a few more years of life. So please read this and absorb it, live the life of a reckless and courageous soul. I only ask that you live it through the book and if your soul seeks a greater challenge, that you prepare yourself for any eventuality.