PHILADELPHIA MAGAZINE: I could tell you about Muneera Walker, a 53-year-old African-American general contractor who was driving along winding, dangerous Mill Creek Road in Gladwyne when a car behind her raced up to her bumper. The car drew perilously close in her rearview mirror, dropped back, then surged forward again, as if urging Walker to hit the gas. She could see the driver, a young white woman around 20 years old, in her rearview mirror.

This was a balmy day last August. Both drivers had their windows rolled down, and as Walker maintained her speed, around 30 mph, she reached one hand out her driver’s-side window, urging the young woman to slow down. The next thing she knew, the young woman leaned, head and shoulders, out her window, waving her cell phone in one hand and steering with the other. “Look at this!” she yelled. “I’m going to call the police. You know they’ll get you! Get your black ass back to Philadelphia where you belong!”

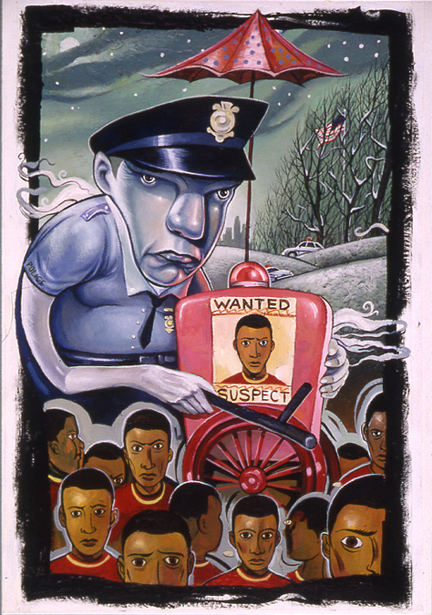

What hurt Walker most is that all her experience told her the woman was right. If the police came and questioned them both, they’d be more likely to believe the young woman. Walker’s own son had recently been ordered out of a local convenience store because, Walker told me, he “looked like some other black kid” who caused trouble there and the staff wasn’t interested in hearing him out. “It spans the generations,” Walker says. “You look at how far we’ve progressed and you realize the further we get, the clearer it is that we really haven’t gotten anywhere. And as a parent, I know my children will face these things. Because I face them.”

We could talk about the schools. Lower Merion is an epicenter of racial tension, with two recent race-based lawsuits. In one case, Blunt v. Lower Merion School District, seven African-American students sued the district for failing to provide the free and appropriate public education to which every child is entitled. The alleged events are heartbreakingly repetitive: Though testing showed the complainants were generally of average intelligence and learning skills in subjects like math, reading and comprehension, they were misidentified as requiring special education.

Parents do have the right to demand that their children be “mainstreamed” and receive a regular curriculum. But according to the plaintiffs’ attorney, Carl Hittinger, some parents initially believed district experts who advised them that their children had learning disabilities. Others claim school officials told them their children were being put into “enrichment programs,” as if they were receiving a bonus.

When parents objected to the district’s treatment, teachers and administrators often confounded them. One woman, Aginah Carter-Shabazz, says requests that her grandchild be mainstreamed were simply ignored. Another parent said she received paperwork indicating that her child would enter middle school in the regular curriculum. Come the fall, it turned out Penn Wynne staff had forwarded an entirely different set of paperwork to the child’s new school. The girl was enrolled, despite her mother’s wishes, in a special-education program.

During court proceedings for the case, a school psychologist admitted that he’d lied to two parents by saying that the testing protocols — the scoring methods — for their child were “destroyed.” Under oath, he admitted the protocols were intact. The impact of such attitudes and actions can be seen not only in Lower Merion, but also in nationwide education statistics. African-American children are 1.4 times as likely as white children to end up in special-education programs.

The Fridays have also been touched by this issue: While they were living in Stamford, Connecticut, school officials directed Anita Friday’s eldest son into a remedial class.

She didn’t believe the recommendation. She had his IQ tested. When he scored at the genius level, she saw the principal.

“Aren’t you a lawyer?” the principal asked.

“Yes,” replied Friday.

“Well, you’re one of the good ones,” she says the principal replied. “We’ll put him in regular classes.” MORE