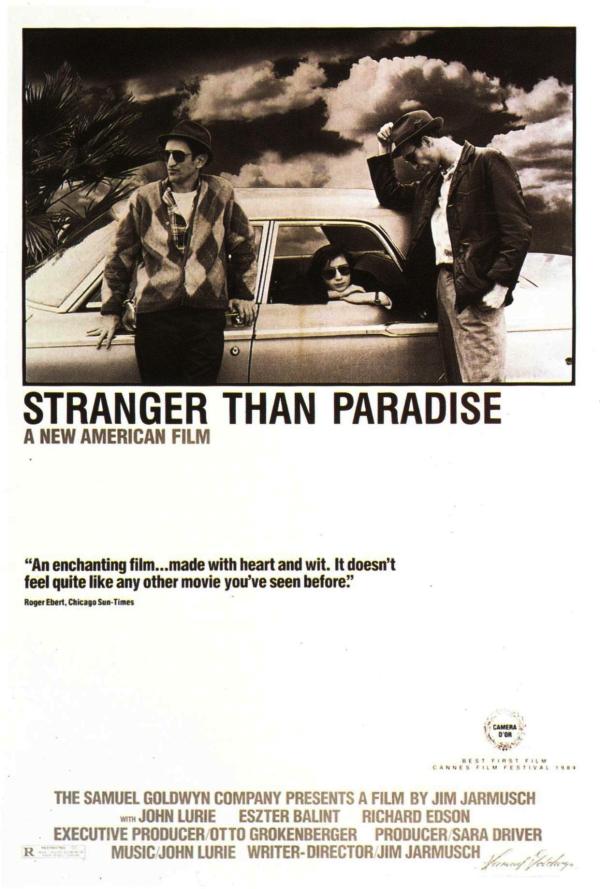

STRANGER THAN PARADISE (1984, directed by Jim Jarmusch, 89 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Jim Jarmusch’s first widely-distributed film, 1984’s Stranger Than Paradise, is a Criterion-endorsed modern classic, often pegged as being a crucial cog in the birth of the American independent film movement. But how does it play today? You’ll get a chance to see how this seminal slacker comedy plays with an modern audience this Saturday when The International House on the UPenn campus runs the dryly-comic yarn as part of its celebration of films from art house institution Janus Films.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Jim Jarmusch’s first widely-distributed film, 1984’s Stranger Than Paradise, is a Criterion-endorsed modern classic, often pegged as being a crucial cog in the birth of the American independent film movement. But how does it play today? You’ll get a chance to see how this seminal slacker comedy plays with an modern audience this Saturday when The International House on the UPenn campus runs the dryly-comic yarn as part of its celebration of films from art house institution Janus Films.

It would seem dishonest not to confess that my feelings for the film are deeply tied to the context of the times and my then-burgeoning interest in film. At 19, just before the rise of the VCR, interest in film history was mostly pursued in repertory movie theaters and college campuses, and I was beginning to haunt both to piece together some sense of the world’s cinema. When I saw Stranger Than Paradise in 1984 it was at the musty but cozy State Theater in Newark, Delaware and it was a revelation. I’d seen The 400 Blows but the French New Wave was still a discovery away. By the time Jarmusch made Stranger he was a cinéaste who had haunted Paris’ Cinémathèque Française and had absorbed not just the New Wave but the ideas of Bresson, Ozu and Antonioni. With its artful display of spare composition, single shot master takes and the particular power of black and white film, Stranger Than Paradise did not arrive just as a film, but as a whole universe of possibility introducing itself. Talking to others about the film, its seem like I’m not the only one of my generation who felt that discovery, and much of the impact of the film was in Stranger’s arrival in that particular historical moment. What would this most delicate of triumphs feel like in 2012?

In a film that depends so much on its dead-pan rhythms, absent punchlines and dead time, seeing the film communally in a theater is the ideal environment. However, for me this viewing  was much different than my first. Could I have imagined in 1984 that today, after desperately searching my home for the DVD I picked up a few years back, I would finally just dial it up from YouTube and watch it in six 15-minute segments? I did my best to give myself over to its long silences but darn if I didn’t take a few breaks to check Facebook, and headlines. I do feel shame for this.

was much different than my first. Could I have imagined in 1984 that today, after desperately searching my home for the DVD I picked up a few years back, I would finally just dial it up from YouTube and watch it in six 15-minute segments? I did my best to give myself over to its long silences but darn if I didn’t take a few breaks to check Facebook, and headlines. I do feel shame for this.

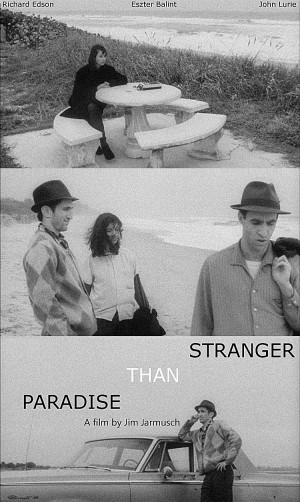

Yet quickly the film worked it same charms: the unaffected performances, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, and the tension of things threatening to happen that never do. Shot in mostly unmoving master shots, Stranger has no real edits, we’re just there to stare unblinkingly at moments of its shiftless characters semi-eventful lives. Like Ralph and Ed Norton in The Honeymooners, Willie (John Lurie) and Eddie (former Sonic Youth member Richard Edson) are a couple of New Yorkers looking to get an angle on life. Musician John Lurie is still a gas as Willie. Lurie could have gone on to a career on cops shows or anything that needed that ethnic New York feel, yet instead has lived out an intriguing career on the hepcat periphery, occasionally releasing brilliant mood music, hosting the most conceptual fishing show of all time, and in recent years as a visual artist (whose recent life was profiled in a bizarre New Yorker article back in 2010). Lurie’s agitated and adrift Willie sets a tone off of which every other actor reacts. Willie is also aggressively American, extolling the virtues of TV dinners, falling asleep in a cathode glow and defensively proclaiming to Eddie, “I’m as American as you!”

Willie needs to justify in American status because a visit from his heavily accented Hungarian cousin, the pretty teenage Eva (Eszter Balint,) is casting doubt on his pose. He’s irritated by her foreignness, he forbids her to speak Hungarian, he buys her a dress so she’ll pass as a local and coaches her on the basics of American culture. Eva finally wins Willie over when she shoplifts a TV dinner for him, whatever the American dream means to Willie, it doesn’t mean working hard and playing fair.

The first third, set mainly in cramped NYC apartments and titled “The New World,” was originally screened as a short and its success led Jarmusch to expand it to feature length. The following two segments, “One Year Later” and “Paradise” take Willie And Eddie on the road and we realize the empty shiftlessness that defines them travels with them as well. Both Jarmusch’s New York City and the road trip across the States present a world this is barren and under-populated. Seen today, cell phones are more noticeable than ever for their absence; these characters, together and separately are empty and alone and there is no satellite-connected lifeline available. Willie and Eddie head to Cleveland “on vacation” (vacation from exactly what being the joke) to visit Eva and Willie’s Hungarian Aunt Lotte (Cecilia Stark, who like all the non-actor cast, gives an amazing performance.) Again, Willie is embarrassed by Aunt Lotte’s foreignness, and after doing pretty much nothing, Willie convinces Eva and Eddie to take a trip to Florida on a whim.

Today, the unmotivated Willie and Eddie have a whole wealth of slacker archetypes in which to fit, but as the overachieving hustle of ’80s Reaganism was hitting its stride, this pair seemed revolutionary in their deep-seated disinterest. Originally, when Willie deported himself back to his reviled Hungary through a comedy of errors it almost seemed like just desserts, maybe this guy was too slack to cut it in the U.S. in 1984. But what will today’s audience think of Willie’s fate? Jarmusch’s oddly timeless landscape is a bleak picture of America that is not just lacking in ambition but opportunity as well. With a “lost decade” of youth unemployment in America, and with no end in sight, the “new world” of Budapest is likely today to be seen as more enticing than ever.