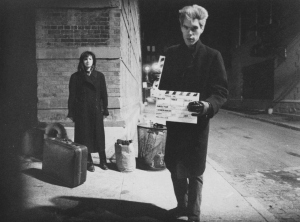

Eszter Balint, best known as the then-16-year-old star of Jim Jarmusch’s career-making, tide-changing, genre-defining 1984 indie flick STRANGER THAN PARADISE, has a new and quite good album out called Airless Midnight. Her acting career was revived recently when Louis CK cast her as his non-English speaking Hungarian love interest for six episodes of Louie. A few weeks ago Phawker conducted a comprehensive five-hour interview with her. By her admission, it’s the most in-depth and revealing interview she’s ever done. Very interesting stuff. Her father was an celebrated experimental playwright in Hungary who fled to New York in 1977 when his work ran afoul of the Communist authorities and set up an off-off-Broadway theater in Chelsea that became a gathering place for many soon-to-be-famous denizens of the NYC underground art and music scenes: Susan Sontag, Jonathan Demme, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Julian Schnabel, John Lurie, Jarmusch, Screaming Jay Hawkins, to name but a few. These are the people Eszter Balint rubbed elbows with when she was a teenager. She was very good friends with Jean Michel Basquiat and played, at his behest, on the little-known hip-hop single he recorded before his death. After STRANGER THAN PARADISE became a hit she was cast in Woody Allen’s NIGHT AND FOG where she worked with Mia Farrow and John Malkovich, as well as Steve Buscemi’s TREE’S LOUNGE and starred opposite David Bowie in THE LINGUINI INCIDENT. From there she transitioned into music, writing, recording and releasing two well-received albums in the early aughts, appears on the second album by Mark Ribot’s legendary Los Cubanos Postizos and was a touring member of Cerarmic Dog. She is a classically-trained singer/violinist and a gifted lyricist, in the Leonard Cohen/Nick Cave vein, who writes these inscrutable noirish tone poems telegraphing the midnight of the soul. Look for it next week on a Phawker near you!

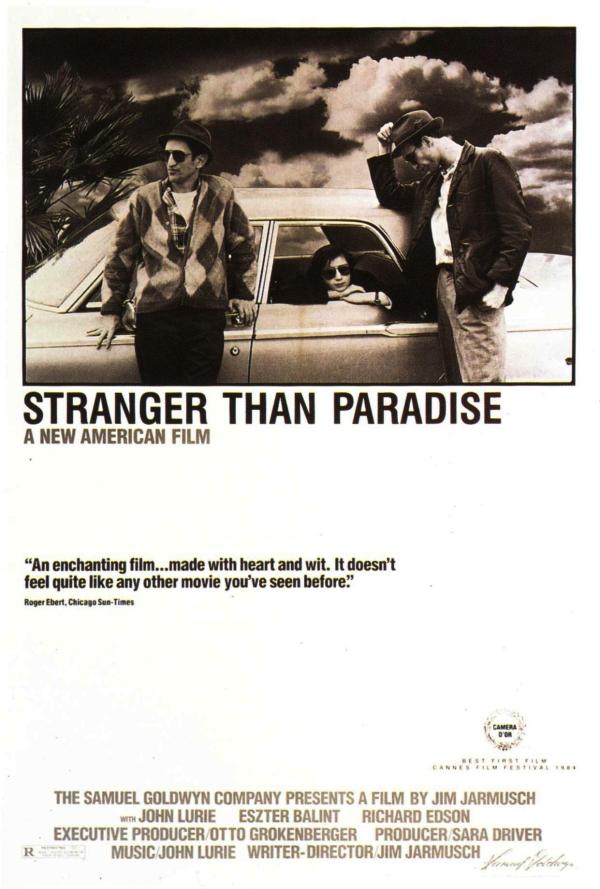

FILM SPECTRUM: After John Cassavetes invented modern independent cinema in late the ’60s, there was no more important figure in the movement’s growth than Jim Jarmusch, a pioneer who rose to cult fame during the ’80s and the infancy of Sundance. Jarmusch got his start as an assistant under the invaluable mentors Nicholas Ray and Wim Wenders, at which point he decided to forgo his NYU film school graduation and put the rest of his scholarship money toward his first film, Permanent Vacation (1980). With great reviews, Jarmusch went onto his next project, taking leftover stock footage from Wenders’ Der Stand der Dinge (1982) and creating his own 30-minute short subject film, Stranger Than Paradise.

When the film hit the festival circuit, including the 1983 International Film Festival Rotterdam, Jarmusch used its warm reception to raise money to turn it into a full-length  feature. The result was a piece of film history, playing at the first annual Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Special Jury Prize but lost the Grand Jury Prize to the Coen Brothers’ Blood Simple (1984). Jarmusch got a measure of retribution at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, where Paradise won the Camera D’Or on the same night his mentor, Wenders, won the top prize, the Golden Palm, for Paris, Texas (1984). For the rest of the ’80s, there were few more internationally renowned “art” filmmakers than Wenders and Jarmusch.

feature. The result was a piece of film history, playing at the first annual Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Special Jury Prize but lost the Grand Jury Prize to the Coen Brothers’ Blood Simple (1984). Jarmusch got a measure of retribution at the 1984 Cannes Film Festival, where Paradise won the Camera D’Or on the same night his mentor, Wenders, won the top prize, the Golden Palm, for Paris, Texas (1984). For the rest of the ’80s, there were few more internationally renowned “art” filmmakers than Wenders and Jarmusch.

Jarmusch has since defined himself as a social commentator on the basic human similarities shared by international cultures, leaving a trail of fascinating works from his short Coffee and Cigarettes (1986) to features like Down By Law (1986), starring Tom Waits, Night on Earth (1991), starring Gena Rowlands, and Dead Man (1995), starring Johnny Depp. His continued underground rise makes it all the more important, and telling, to go back and look at Paradise, in which many of these seeds were sewn. And beyond origin, Stranger Than Paradise may still very well be his most important work. MORE

WIKIPEDIA: Jalacy Hawkins (July 18, 1929 – February 12, 2000), better known by the stage name Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, was an American rhythm and blues musician, singer, songwriter and actor. Famed chiefly for his powerful, operatic vocal delivery, and wildly theatrical performances of songs such as “I Put a Spell on You“, he sometimes used macabre props onstage, making him an early pioneer of shock rock.[1] Hawkins’ most successful recording, “I Put a Spell on You” (1956), was selected as one of The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s 500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll. According to the AllMusic Guide to the Blues, “Hawkins originally envisioned the tune as a refined ballad.”[3] The entire band was intoxicated during a recording session where “Hawkins screamed, grunted, and gurgled his way through the tune with utter drunken abandon.”[3] The resulting performance was no ballad but instead a “raw, guttural track” that became his greatest commercial success and reportedly surpassed a million copies in sales,[5][6] although it failed to make the Billboard pop or R&B charts.[7][8]

The performance was mesmerizing, although Hawkins himself blacked out and was unable to remember the session.[6] Afterward he had to relearn the song from the recorded version.[6] Meanwhile the record label released a second version of the single, removing most of the grunts that had embellished the original performance; this was in response to complaints about the recording’s overt sexuality.[6] Nonetheless it was banned from radio in some areas. Soon after the release of “I Put a Spell on You”, radio disc jockey Alan Freed offered Hawkins $300 to emerge from a coffin onstage.[5] Hawkins accepted and soon created an outlandish stage persona in which performances began with the coffin and included “gold and leopardskin costumes and notable voodoo stage props, such as his smoking skull on a stick – named Henry – and rubber snakes.”[5] These props were suggestive of voodoo, but also presented with comic overtones that invited comparison to “a black Vincent Price.”[2][6]