FRESH AIR

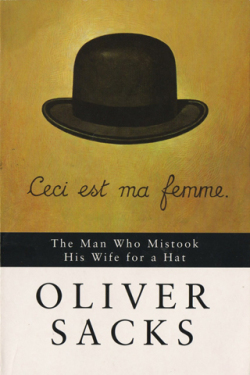

Neurologist Oliver Sacks, who died Sunday, once described himself as an “old Jewish atheist,” but during the decades he spent studying the human brain, he sometimes found himself recording experiences that he likened to a godly cosmic force. Such was the case once when Sacks tried marijuana in the 1960s: He was looking at his hand, and it appeared to be retreating from him, yet getting larger and larger. “I was fascinated that one could have such perceptual changes, and also  that they went with a certain feeling of significance, an almost numinous feeling,” Sacks told Fresh Air’s Terry Gross in 2012. “I’m strongly atheist by disposition, but nonetheless when this happened, I couldn’t help thinking, ‘That must be what the hand of God is like.’ ” Sacks was the author of numerous books that examined the mysteries of perception, memory and consciousness. Often his books described patients with with unusual neurological disorders and brain injuries — such as The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. Sacks’ 1973 book Awakenings, which was adapted into a film starring Robin Williams and Robert DeNiro, chronicled Sacks’ work treating patients who had spent decades in a catatonic state caused by encephalitic lethargica. Some of the patients emerged from their catatonia after Sacks administered the drug L-dopa. In a 1985 interview, Sacks told Gross that watching the patients emerge from the catatonic state was like standing at “the intersection of fact and fable. You see infinitely moving, dramatic, romantic situations, but also clearly based on the state of the nervous system.” Fresh Air remembers Sacks with two interviews from 1985 and 2012. MORE

that they went with a certain feeling of significance, an almost numinous feeling,” Sacks told Fresh Air’s Terry Gross in 2012. “I’m strongly atheist by disposition, but nonetheless when this happened, I couldn’t help thinking, ‘That must be what the hand of God is like.’ ” Sacks was the author of numerous books that examined the mysteries of perception, memory and consciousness. Often his books described patients with with unusual neurological disorders and brain injuries — such as The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat. Sacks’ 1973 book Awakenings, which was adapted into a film starring Robin Williams and Robert DeNiro, chronicled Sacks’ work treating patients who had spent decades in a catatonic state caused by encephalitic lethargica. Some of the patients emerged from their catatonia after Sacks administered the drug L-dopa. In a 1985 interview, Sacks told Gross that watching the patients emerge from the catatonic state was like standing at “the intersection of fact and fable. You see infinitely moving, dramatic, romantic situations, but also clearly based on the state of the nervous system.” Fresh Air remembers Sacks with two interviews from 1985 and 2012. MORE

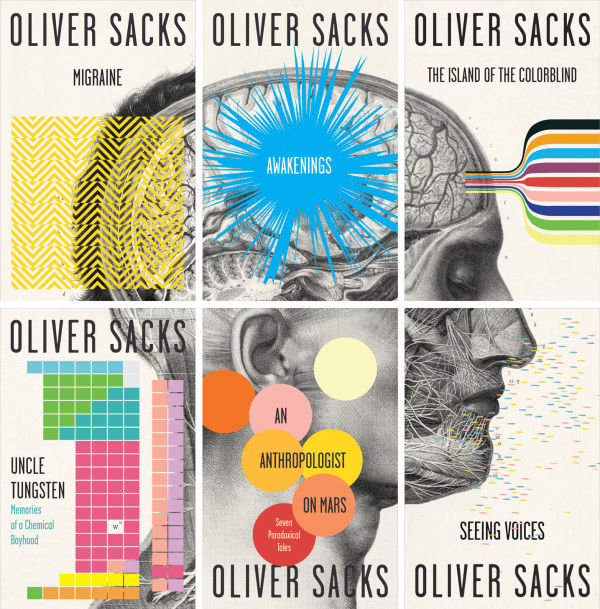

THE ATLANTIC: The Oliver Sacks Reading List

NEW YORK TIMES: Oliver Sacks, the neurologist and acclaimed author who explored some of the brain’s strangest pathways in best-selling case histories like “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” using his patients’ disorders as starting points for eloquent meditations on consciousness and the human condition, died on Sunday at his home in Manhattan. He was 82. The cause was cancer, said Kate Edgar, his longtime personal assistant. Dr. Sacks announced in February, in an Op-Ed essay in The New York Times, that an earlier melanoma in his eye had spread to his liver and that he was in the late stages of terminal cancer. As a medical doctor and a writer, Dr. Sacks achieved a level of popular renown rare among scientists. More than a million copies of his books are in print in the United States, his work was adapted for film and stage, and he received about 10,000 letters a year. (“I invariably reply to people under 10, over 90 or in prison,” he once said.) Dr. Sacks variously described his books and essays as case histories, pathographies, clinical tales or “neurological novels.” His subjects included Madeleine J., a blind woman who perceived her hands only as useless “lumps of dough”; Jimmie G., a submarine radio operator whose amnesia stranded him for more than three decades in 1945; and Dr. P. — the man who mistook his wife for a hat — whose brain lost the ability to decipher what his eyes were seeing. Describing his patients’ struggles and sometimes uncanny gifts, Dr. Sacks helped introduce syndromes like Tourette’s or Asperger’s to a general audience. But he illuminated their characters as much as their conditions; he humanized and demystified them. In his emphasis on case histories, Dr. Sacks modeled himself after a questing breed of 19th-century physicians, who well understood how little they and their peers knew about the workings of the human animal and who saw medical science as a vast, largely uncharted wilderness to be tamed. “I had always liked to see myself as a naturalist or explorer,” Dr. Sacks wrote in “A Leg to Stand On” (1984), about his own experiences recovering from muscle surgery. “I had explored many strange, neuropsychological lands — the furthest Arctics and Tropics of neurological disorder.” His intellectual curiosity took him even further. On his website, Dr. Sacks maintained a partial list of topics he had written about. It included aging, amnesia, color, deafness, dreams, ferns, Freud, hallucinations, neural Darwinism, phantom limbs, photography, pre-Columbian history, swimming and twins. MORE

doctor and a writer, Dr. Sacks achieved a level of popular renown rare among scientists. More than a million copies of his books are in print in the United States, his work was adapted for film and stage, and he received about 10,000 letters a year. (“I invariably reply to people under 10, over 90 or in prison,” he once said.) Dr. Sacks variously described his books and essays as case histories, pathographies, clinical tales or “neurological novels.” His subjects included Madeleine J., a blind woman who perceived her hands only as useless “lumps of dough”; Jimmie G., a submarine radio operator whose amnesia stranded him for more than three decades in 1945; and Dr. P. — the man who mistook his wife for a hat — whose brain lost the ability to decipher what his eyes were seeing. Describing his patients’ struggles and sometimes uncanny gifts, Dr. Sacks helped introduce syndromes like Tourette’s or Asperger’s to a general audience. But he illuminated their characters as much as their conditions; he humanized and demystified them. In his emphasis on case histories, Dr. Sacks modeled himself after a questing breed of 19th-century physicians, who well understood how little they and their peers knew about the workings of the human animal and who saw medical science as a vast, largely uncharted wilderness to be tamed. “I had always liked to see myself as a naturalist or explorer,” Dr. Sacks wrote in “A Leg to Stand On” (1984), about his own experiences recovering from muscle surgery. “I had explored many strange, neuropsychological lands — the furthest Arctics and Tropics of neurological disorder.” His intellectual curiosity took him even further. On his website, Dr. Sacks maintained a partial list of topics he had written about. It included aging, amnesia, color, deafness, dreams, ferns, Freud, hallucinations, neural Darwinism, phantom limbs, photography, pre-Columbian history, swimming and twins. MORE

VANITY FAIR: I had originally written him a letter, sometime in the late 70s, from my California home. Somehow back in college I had come upon Awakenings, published in 1973, an account of his work with a group of patients who had been warehoused for decades in a home for the incurable—they were “human statues,” locked in trance-like states of near-infinite remove following bouts of a now rare form of encephalitis. Some had been in this condition since the mid-1920s. These people were suddenly brought back to life by Sacks, in 1969, following his administration of the then new “wonder drug” L-dopa, and Sacks described their spring-like awakenings and the harrowing siege of tribulations that followed. In the book, Sacks gave the facility where all this happened the pseudonym “Mount Carmel,” an apparent reference to Saint John of the Cross and his Dark Night of the Soul. But, as I wrote to Sacks in that first letter, his book seemed to me much more Jewish and Kabbalistic than Christian mystical. Was I wrong?

He responded with a hand-pecked typed letter of a good dozen pages, to the effect that, indeed, the old people’s home in question, in the Bronx,  was actually named Beth Abraham; that he himself came from a large and teeming London-based Jewish family; that one of his cousins was in fact the eminent Israeli foreign minister Abba Eban (another, as I would later learn, was Al Capp, of Li’l Abner fame); and that his principal intellectual hero and mentor-at-a-distance, whose influence could be sensed on every page of Awakenings, had been the great Soviet neuropsychologist A.R. Luria, who was likely descended from Isaac Luria, the 16th-century Jewish mystic.

was actually named Beth Abraham; that he himself came from a large and teeming London-based Jewish family; that one of his cousins was in fact the eminent Israeli foreign minister Abba Eban (another, as I would later learn, was Al Capp, of Li’l Abner fame); and that his principal intellectual hero and mentor-at-a-distance, whose influence could be sensed on every page of Awakenings, had been the great Soviet neuropsychologist A.R. Luria, who was likely descended from Isaac Luria, the 16th-century Jewish mystic.

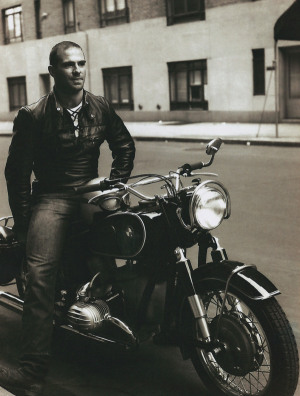

Our correspondence proceeded from there, and when, a few years later, I moved from Los Angeles to New York, I began venturing out to Oliver’s haunts on City Island. Or he would join me for far-flung walkabouts in Manhattan. The successive revelations about his life that made up the better part of our conversations grew ever more intriguing: how both his parents had been doctors and his mother one of the first female surgeons in England; how, during the Second World War, with both his parents consumed by medical duties that began with the Battle of Britain, he, at age eight, had been sent with an older brother, Michael, to a hellhole of a boarding school in the countryside, run by “a headmaster who was an obsessive flagellist, with an unholy bitch for a wife and a 16-year-old daughter who was a pathological snitch”; and how—though his brother emerged shattered by the experience, and to that day lived with his father—he, Oliver, had managed to put himself back together through an ardent love of the periodic table, a version of which he had come upon at the Natural History Museum at South Kensington, and by way of marine-biology classes at St. Paul’s School, which he attended alongside such close lifetime friends as the neurologist and director Jonathan Miller and the exuberant polymath Eric Korn. Oliver described how he gradually became aware of his homosexuality, a fact that, to put it mildly, he did not accept with ease; and how, following college and medical school, he had fled censorious England, first to Canada and then to residencies in San Francisco and Los Angeles, where in his spare hours he made a series of sexual breakthroughs, indulged in staggering bouts of pharmacological experimentation, underwent a fierce regimen of bodybuilding at Muscle Beach (for a time he held a California record, after he performed a full squat with 600 pounds across his shoulders), and racked up more than 100,000 leather-clad miles on his motorcycle. And then one day he gave it all up—the drugs, the sex, the motorcycles, the bodybuilding. By the time we started talking, he had been pretty much celibate for almost two decades. MORE

![]() In Oliver Sacks’ book The Mind’s Eye, the neurologist included an interesting footnote in a chapter about losing vision in one eye because of cancer that said: “In the ’60s, during a period

In Oliver Sacks’ book The Mind’s Eye, the neurologist included an interesting footnote in a chapter about losing vision in one eye because of cancer that said: “In the ’60s, during a period  of experimenting with large doses of amphetamines, I experienced a different sort of vivid mental imagery.” He expands on this footnote in his book, Hallucinations, where he writes about various types of hallucinations — visions triggered by grief, brain injury, migraines, medications and neurological disorders. One chapter of the book — that’s out in paperback July 2 — deals with altered states and Sacks’ personal experimentation with hallucinogenic and mind-altering drugs in the ’60s. He says the first time he tried marijuana, it induced fascinating perceptual distortion. He was looking at his hand, and it appeared to be retreating from him, yet getting larger and larger. “I was fascinated that one could have such perceptual changes, and also that they went with a certain feeling of significance, an almost numinous feeling. I’m strongly atheist by disposition, but nonetheless when this happened, I couldn’t help thinking, ‘That must be what the hand of God is like.’ ” MORE

of experimenting with large doses of amphetamines, I experienced a different sort of vivid mental imagery.” He expands on this footnote in his book, Hallucinations, where he writes about various types of hallucinations — visions triggered by grief, brain injury, migraines, medications and neurological disorders. One chapter of the book — that’s out in paperback July 2 — deals with altered states and Sacks’ personal experimentation with hallucinogenic and mind-altering drugs in the ’60s. He says the first time he tried marijuana, it induced fascinating perceptual distortion. He was looking at his hand, and it appeared to be retreating from him, yet getting larger and larger. “I was fascinated that one could have such perceptual changes, and also that they went with a certain feeling of significance, an almost numinous feeling. I’m strongly atheist by disposition, but nonetheless when this happened, I couldn’t help thinking, ‘That must be what the hand of God is like.’ ” MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: In 1989, interviewing him for “The MacNeil/Lehrer NewsHour,” Joanna Simon asked Dr. Sacks how he would like to be remembered in 100 years. “I would like it to be thought that I had listened carefully to what patients and others have told me,” he said, “that I’ve tried to imagine what it was like for them, and that I tried to convey this. “And, to use a biblical term,” he added, “bore witness.” He also bore witness to his own dwindling life, writing reflective essays even in his last days. On Aug. 10, his assistant, Ms. Edgar, who described herself as his “collaborator, friend, researcher and editor” as well, wrote in an email: “He is still writing with great clarity. We are pretty sure he will go with fountain pen in hand.” Several days later, a valedictory essay titled “Sabbath” appeared in The Times. In it, Dr. Sacks considered the importance of the Sabbath in human culture and concluded:

“And now, weak, short of breath, my once-firm muscles melted away by cancer, I find my thoughts, increasingly, not on the supernatural or spiritual, but on what is meant by living a good and worthwhile life — achieving a sense of peace within oneself. I find my thoughts drifting to the Sabbath, the day of rest, the seventh day of the week, and perhaps the seventh day of one’s life as well, when one can feel that one’s work is done, and one may, in good conscience, rest.” MORE