FRESH AIR

Screenwriter Oren Moverman talks with Fresh Air’s Terry Gross about the film’s depiction of the Beach Boy’s troubled life. We’ll also listen back to an interview Gross recorded with Wilson in 1988.

PREVIOUSLY: Love & Mercy tells the harrowing, heartbreaking story of the life of Brian Wilson — Beach Boys auteur and resident genius — which goes like this: Angel-headed boy from Hawthorne, California, at the dawn of the 1960s, smitten by the harmonic convergence of The Four Freshman and the shimmering Spectorian grandeur of “Be My Baby,” forms band with his two brothers and asshole cousin, calls it The Beach Boys, writes uber-catchy ditties of Zen-like simplicity about surfing, hot rods and girls (despite being slapped deaf in his right ear by his sadistic tyrant of a father), boy becomes international pop star, boy has nervous breakdown and retires from touring and retreats to the studio where he gets into a race with the Beatles to get to the next level, boy takes LSD, boy blows mind, boy sees God, boy starts hearing strange and beautiful music in his head, boy plays the studio like an instrument, sings choirs of angels, creates music of overarching majesty, astonishing beauty and profound sadness, boy makes greatest pop album of all time (Pet Sounds) and the greatest song of the 20th Century (“Good Vibrations”), boy starts hearing terrifying voices in his head, beset by demons Beach Boys With A Surfboardfrom within and without (his sadistic tyrant of a father, his asshole cousin) boy loses mind and, eventually, the confidence of his band mates who pull the plug on his game-changing “teenage symphony to God” originally called Dumb Angel, but later re-titled Smile, boy retreats into a years-long bedroom hermitage of Herculean drug consumption, morbid obesity and sweet insanity, columnated ruins domino, family hires Mephistophelian psychiatrist/psychic vampire Dr. Eugene Landy (played with satanic aplomb by Paul Giamatti), who switches out boy’s steady diet of cocaine, LSD, sloth and  self-pity for a zombie-fying regimen of prescription narcotics, fitness Nazism, and 24-7 mind control, boy meets girl (Melinda Ledbetter, his soon-to-be second wife, played by a big-haired, puffy-shouldered Elizabeth Banks) at a Cadillac dealership and falls in love, girl rescues boy from the clutches of evil doctor, boy lives happily ever after, or a reasonably close approximation thereof.

self-pity for a zombie-fying regimen of prescription narcotics, fitness Nazism, and 24-7 mind control, boy meets girl (Melinda Ledbetter, his soon-to-be second wife, played by a big-haired, puffy-shouldered Elizabeth Banks) at a Cadillac dealership and falls in love, girl rescues boy from the clutches of evil doctor, boy lives happily ever after, or a reasonably close approximation thereof.

Pretty simple, really.

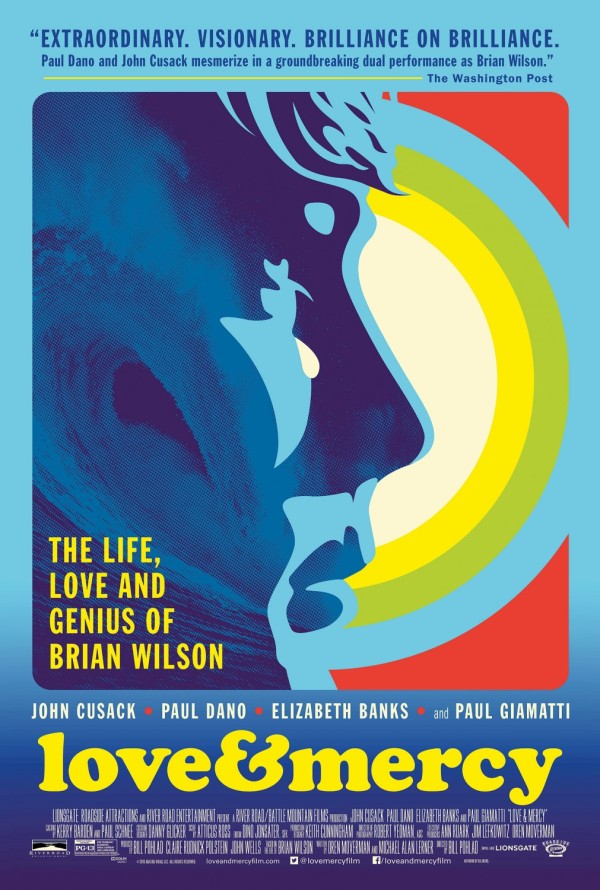

Granted it’s not a story that lends itself to the linear-flow cradle-to-grave biopic treatment, which is no doubt why Love & Mercy director Bill Pohlad (executive producer of Brokeback Mountain, 12 Years A Slave and Tree Of Life) and screenwriter Oren Moverman (I’m Not There, Jesus’ Son) elected to craft a bi-polar narrative that switches back and forth from the middle-aged Brian (played with aptly vacant affect by John Cusack, who eschews impersonation for for understated evocation) and young genius Brian (played with doughy intensity and uncanny resemblance by Paul Dano, who does not so much impersonate young Brian Wilson as inhabit him), in a race to the middle where they collide in the time-space-continuum of Brian’s bedroom in a mind-bending montage that is both loving homage and direct quote of the mysterious metaphysical endgame of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. The ancient, iconic moments of Wilsonian mythos — the barefoot, white Chinos- &-blue Pendelton shirt-wearing, surfboard-toting photo shoot idylls; the terrifying nervous breakdown at 20,000 feet; the acid-fueled, poolside transfiguration; the Wrecking Crew’s adoration of his otherworldly compositional prowess; the drug den wigwam in the living room and the piano in the sandbox; the fireman-hatted Smile session meltdown; the prison of belief in Landy’s methods (less a therapist than a sinister puppeteer) — are recreated in arresting, picture-perfect period detail. The cinematography nails the shifting tone and color and tint of the times and the score and sound design is suitably mind-altering. Pedestrians may quibble, but that will fall away in time. Love & Mercy is a grand and lasting monument to the noble beauty wrung from one man’s epic suffering. It is the story of Icarus on the beach, of the boy who got too high — flew too near the sun on wings of wax — and the man who fell to Earth. — JONATHAN VALANIA

PREVIOUSLY: Discussing Love & Mercy With Brian Wilson