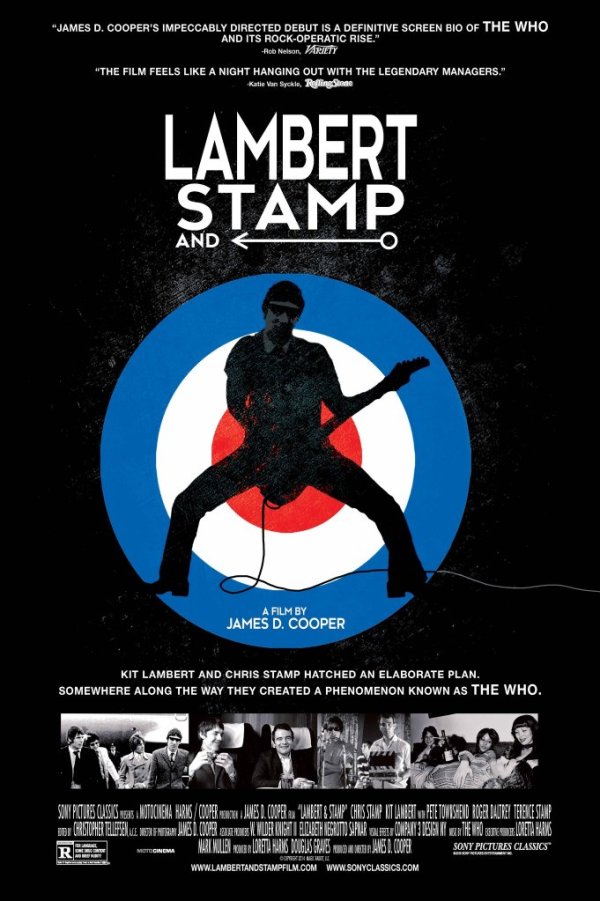

LAMBERT & STAMP (2014, directed by James D. Cooper, 117 minutes, U.S.)

![]() BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC The 1979 documentary The Kids Are Alright was one of the early classics of the rockumentary genre, a mad bash-up with the four characters who made up The Who. The film did a lot to burnish their artistic legend but years later it is apparent that the doc left out the guiding force that nurtured them into the band they would become: the visionary management of the duo known as Lambert & Stamp. Director James D. Cooper’s unusually intimate portrait of the band’s early years brings a whole new dimension to The Who’s ascent, painting the story of their rise to pop stardom as a grand, audacious heist.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC The 1979 documentary The Kids Are Alright was one of the early classics of the rockumentary genre, a mad bash-up with the four characters who made up The Who. The film did a lot to burnish their artistic legend but years later it is apparent that the doc left out the guiding force that nurtured them into the band they would become: the visionary management of the duo known as Lambert & Stamp. Director James D. Cooper’s unusually intimate portrait of the band’s early years brings a whole new dimension to The Who’s ascent, painting the story of their rise to pop stardom as a grand, audacious heist.

Kit Lambert was the gay, under-achieving son the famed British composer Constant Lambert and he was born into aristocracy. Chris Stamp is the working class son of a tugboat captain from the East End of London whose older brother Terrence had just become a major film star. This odd couple met while working as assistants at Shepperton Studios. When they realize their dreams of directing films aren’t coming true, Stamp sells Lambert on the idea of putting their energies into managing a rock band. The plan is to make the band stars and then they’ll produce and direct a big screen vehicle for the group that will be their ticket into the film world. When they first discover The Who (then still known as The High Numbers), the band specializes in a primitive brand of dance-oriented American R&B and Townshend has yet to write a single song, but Lambert and Stamp see something outrageous about the quartet that captures their imagination. Now all the pair has to do is make the band stars and hopefully they’ll get a film out the spectacle before the whole under-financed operation collapses under its own weight. Because how long could this rock and roll fad last anyway?

Lambert & Stamp makes you feel like you’re part of this grand scheme and here’s a giddy thrill to the stories Stamp spins (Lambert died back in 1981) about opening up bank accounts and getting large advances merely because they were able to get a flat in the posh part of London. During those early instrument-trashing days, the band’s finances were constantly in the red but to the band’s managers it didn’t matter, they were only in this long enough to get their film made. It’s Townshend’s rock opera Tommy that looks to be the film vehicle they’re waiting for but as Stamp and Lambert get ready to bring their scheme to fruition, the well-planned plot implodes.

Stamp would go on to become a psychotherapist, and the film seems very aware the psychological motivations of its players. Particularly touching is Stamp’s remembrance of his friendship with Lambert. He tells the camera that having a gay friend, in a time when he himself wasn’t quite comfortable around women, allowed him to develop a sensitivity and intimacy he would not have otherwise. Townshend and Daltrey are interviewed at length as well and they are unusually open about the psychological state they found themselves in at the height of their youthful fame. All of which makes for a rich and revealing story about business and friendship.

Not that the film slights the musical aspect either. Because Lambert & Stamp were filmmakers, the documentary holds some beautiful, rarely-seen footage of the band as their image is being built and no expense seems to have been spared to fill the film with glorious images of the swinging ’60s. But the film’s record of the band’s artistic rise is overshadowed by the emotions and stories of these two men who have languished in the background all these years. For rock fans this new angle on the rise of The Who isn’t just thrilling, it’s a revelation.